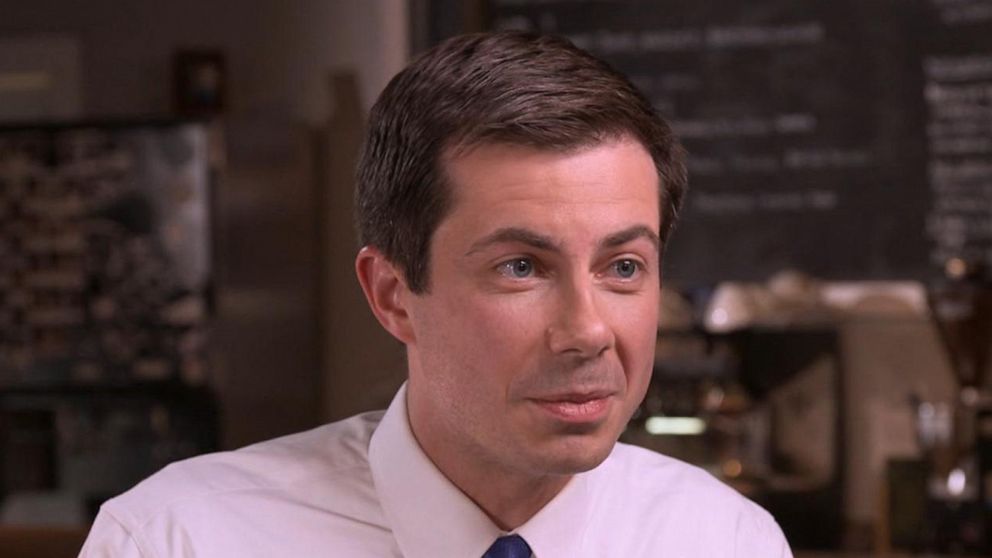

Pete Buttigieg is Being Attack For Being The Gay, Americans Don't Understand

This article which just came out is one of those I agree with and enjoyed reading it. Not everything I post I agree with because news is news, particularly about the LGBTQ community which is so diverse in opinions. Adam

This post is part of Outward, Slate’s home for coverage of LGBTQ life thought, and culture.

As Pete Buttigieg rises in the polls in early caucus and primary states like Iowa and New Hampshire, criticism of the candidate has mounted, particularly around his personality. Since entering the field, initial appreciation for the South Bend, Indiana, mayor’s relative youth and rolled-sleeves Midwestern energy has given way to a sense in certain incredulous quarters that he is robotic, overly polished, McKinsey-calculating, somehow fake. A related discontent has emerged in some corners of the LGBTQ community around Buttigieg’s relationship to his own gay identity. Here, too, he can come off as strangely circumspect, seemingly distant from gay culture and history—despite making it as the first serious openly gay presidential candidate. The privileges of race, class, and gender presentation that allow for his “pioneer” status relative to other sorts of queer people (and Buttigieg’s tepid acknowledgment of these) is another sore point.

I’ll be the first to admit that Buttigieg is missing a certain warmth. And I’ve critiqued his lack of familiarity with gay history in the past. Even so, as a gay historian, I can’t help but witness his rise with interest and excitement, and in the wake of last week’s presidential debate and a revealing interview with Buttigieg on the New York Times’ Daily podcast, a worry has emerged. I’ve come to believe that those who find his self-presentation off-putting are missing an important bit of context—one that has to do with the set of archetypes through which we (queer and straight folks alike) make sense of gay men.

For all the talk of diversity, LGBTQ equality, and representation of gays in the media, many Americans still have limited exposure to gay men. Many know of comical gay men, like Jack from Will & Grace or videos of Billy Eichner’s street antics. They know of attention-grabbing gay men like Liberace and Billy Porter. They know of the hot gay men like Wentworth Miller and Gus Kenworthy. They also know the American sweethearts like Adam Rippon and Anderson Cooper. A subspecies they aren’t as familiar with, however, is the Type A, politically driven, never-take-their-eye-off-the-ball gays—a group of which Pete Buttigieg is an extreme example.

A subspecies Americans aren’t as familiar with is the Type A, politically driven, never-take-their-eye-off-the-ball gays.

I’ve come to know dozens of this kind of gay man throughout my life, particularly when I was in my 20s, during summer vacations in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, in the late 1990s. A group of us would rent a beach house for a week or even the season. We would all pile into it like a frat house, sleeping four to a room with two double beds, some left to sleeping on the living room floor under the air conditioner (me); some sleeping in the un-air-conditioned, haunted attic (also me); some sleeping on the cool cement floor on the dank laundry room, (fortunately not me).

We would spend our days at the beach flipping through entertainment magazines and gossiping about who just pranced by in a Speedo. We would spend our evenings at house parties and crowded bars. And, on Sunday mornings, before we packed up our cars and left, we carpeted the outdoor porch with the weekend newspapers and discussed politics, vigorously. And there was always at least one, or even two, in the group: the guy who was not hungover, who was not wearing someone’s else boxers, but who was instead pristinely dressed in crisp polo shirts and who, like Buttigieg, would rattle off oral essays on anything from foreign relations in the Middle East to the benefits of flying with Air France.

One particular guy I recall from this time had a penchant for planning every meal that we ate and organizing everything from the time we left for the beach to the first cocktail of the evening. This earned him the name of “Schedule Spice.” It was the late 1990s and, being enamored by the Spice Girls, I created a nickname for everyone: Old Spice, Senator Spice, Italian Spice. And Schedule, who sent love letters by FedEx to his new boyfriend (because it was the era before texting), could answer any question on a moment’s notice, from how to fix the overflowing toilet to the impact of Reaganomics, with ease and alacrity.

So, when I see people dismissing or disliking Buttigieg for his stoicism, his carefully tended résumé, for being “a script, a blandly pasteurized politician,” I see them attacking Schedule Spice and the dozens of other gay men I knew like him.

Viewed through the lens of Schedule Spice, Buttigieg’s persona and life trajectory make complete sense. To my mind, he is the natural end result of a very familiar queer pattern that groomed him for this moment. His religious devotion to mastering the perfect pedigree, his refusal to be single, his denial of any type of popular gay aesthetic (which is, itself, another kind of gay aesthetic) makes him legible to me. His academic nerdiness combined with his über-masculine military service is not a genuflection to heteronormativity, as some have claimed, but a familiar gay identity curated among upwardly mobile white gay men who have often turned to politics in one form or another. The only difference is that Schedule Spice is now vying for the presidency.

Psychologists have analyzed the relationship between a Type A personality, adolescence in the closet, and a need for perfection. Taking their cue from Andrew Tobias’ bestselling memoir, they have developed a theory of the “the Best Boy in the World,” which essentially means that in order to deflect attention away from their closeted sexuality, some gay men have overcompensated in their career or in other areas that award success. Growing up in the Midwest, Buttigieg has explained, made him think that he had to choose between being an elected politician or an out gay person. Unfortunately, unlike me, he never got to meet a summer house full of gay men who didn’t view their gay identity in opposition to their commitment to politics and public life.

Critics of Mayor Pete’s demeanor don’t recognize that his persona reflects the consequence of living in the closet, or “packing away his feelings,” as he put it to The Daily. Despite eventually coming out, getting married, and being the first openly gay man on the Democratic presidential primary stage, the coping mechanisms that he developed from being in the closet did not immediately vanish. When people criticize him for being calculated or robotic, I see the familiar traits of a gay man who had desperately tried to live in both worlds.

Often, homophobia is easy to spot. It’s easy to call it out, for example, when haters refer to Buttigieg as a woman, as they did after Amy Klobuchar jabbed him during Wednesday’s debate by saying that a female mayor would not be on the stage. It’s also readily visible in the realization that the Supreme Court could invalidate Mayor Pete’s marriage even if he were the sitting president.

It’s harder to name the prejudice and discrimination when critics indict Mayor Pete for a deportment that he cultivated in order to survive. During Tuesday’s debate, one critic on Twitter suggested that someone should just give him another Boy Scout badge so he would sit down. But appearing as a Boy Scout was how he likely survived. It’s evidence of how he straddled a painful divide, of how he felt he was forced to choose one career and life over another. When critics make these gibes, they intend to be clever, even humorous—but what they don’t realize is that they are attacking the shields that many gay men have fortified to defend themselves. And when other gay men—ostensibly familiar with best little boys in their own circles—participate in the pile-on, they are unfortunately fueling a slippery kind of homophobia.

While his model of gayness might not be widely familiar, Buttigieg’s Boy Scouting, his default of being the best little boy on the stage, is legitimately queer. If it strikes us as odd, it’s only because we have too narrow a definition of how a gay man can be in the world. Understanding Buttigieg through this lens does not, of course, have any bearing on his proposals or problems, such as his poor track record among black voters back home or his campaign’s recent foible of using stock images of Kenyans to represent black Americans. By all means, criticize those. But attacks on his “wonder boy” perfection, his encyclopedic knowledge, and his manner demean him and the many gay men like him—men who marry the first guy they date, who don’t come out till their late 20s, who are socially awkward, who have devoted their lives to work, and whose musical default is not gay pop. Men who, most of all, are raring to discuss politics at any moment, particularly on Sunday morning.

Comments