{Page 6 HIV News} The HIV Vaccine Given Slow Gets Immune Response

|

| Dr. Luis Montaner, seated right, with his team at the HIV Cure and Viral Diseases Center at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia | Wistar Institute |

Greg Owen

|

| Healthcare, black man and doctor with clipboard, diagnosis and conversation for results, smile and care. Male patient, guy and medical professional with documents, paperwork for insurance and talking |

We have now a whole inventory of strategies to empower the immune system to clear an infected cell, but we still want to identify a strategy that can effectively expose a cell as infected. I’m quite confident that if we continue the investment, the outcome would be successful.

|

| A 3D medical illustration showing an HIV retrovirus targeting T-cells. | ShutterstockT |

|

| llustration showing cross-section of a lipid nanoparticle carrying mRNA of the virus (orange) | Shutterstock |

The chances of transmitting HIV through oral sex are very low.

HIV spreads through some bodily fluids. The virus can pass through direct contact with fluid or through sharing syringes.

In this article, we describe the transmission of HIV through oral sex and give some tips for prevention.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there is little to no risk of HIV passing through oral sex.

However, it might happen if someone with HIV ejaculates into the mouth of a sexual partner.

This transmission is only possible if the person ejaculating has a detectable “viral load,” which refers to the amount of HIV present in the blood.

Antiretroviral medications reduce the number of viral cells in the body, which can eventually result in an undetectable viral load. For someone with an undetectable viral load, the chances of transmitting HIV through any sexual activity is effectively zero.

Also, the virus might transmit during oral sex if the vaginal fluid of someone with HIV enters a partner’s bloodstream through cuts or sores in their mouth.

As the CDC report, HIV cannot pass from person to person through:

- saliva

- the air

- water

- sweat

- tears

- closed mouth kissing

- insects

- pets

- sharing toilets

- sharing foods or drinks

The virus can only transmit through contact with:

- blood

- semen

- pre-seminal fluid

- rectal fluids

- vaginal fluids

- breast milk

These fluids might enter the bloodstream through damaged tissue or mucous membranes, or by injection using shared needles or syringes.

Parts of the body with mucous membranes include the:

- rectum

- vagina

- penis

- mouth

HIV can also pass through oral sores, cuts in or around the mouth, or bleeding gums during open-mouthed kissing. If a person does not have sores, cuts, or bleeding gums, it is safe to kiss.

The most common way of transmitting HIV is through anal sex.

During oral sex, the transmission of HIV is possible if someone who has a detectable viral load ejaculates into the mouth of a sexual partner.

For this reason, fellatio, or mouth-to-penis sex, is the kind of oral sex most likely to result in HIV transmission. The risk is higher if the partner has bleeding gums or oral sores or cuts.

However, the chances of the virus passing in this way are still substantially lower than the risks associated with anal or vaginal sex.

During cunnilingus, or mouth-to-vagina sex, HIV can pass via vaginal fluid. This is more of a risk if the person performing the cunnilingus has oral cuts, oral sores, or bleeding gums.

When is the risk higher?

HIV is more likely to pass to others during the early stages of the infection.

Some factors that increase the risk of transmission include:

- sores or cuts in the mouth

- sores in or around the vagina or penis

- bleeding gums or gum disease

- contact with menstrual blood

- the presence of any other sexually transmitted infection

- the presence of a throat infection

- damage to the lining of the throat or mouth

Private HIV Stories

An Answer to questions or remarks on mid week June 2020:

For a gay man HIV have become the first deadly thing that could kill us because loving is very hard to stop. Most of us yearn for this and having someone stop, it not an esy command to follow (was told many time, "fuck it, they can't take love from me".. COVID-19 Already shows how weak it is compare to AIDS. To get AIDS first you had to become HIV but the problem was information that was kept from the community hopping that they would die and the world would get rid of gays. With COVID-19 you have to not wear your mask in public and not wear gloves if your job requires you to touch things others have touch before you ou need gloves too. You follow that....and 'there has been no indication that you will get it'. How can we know? Because we know how it spreads. That was the first bullet, no silver bullet but a bullet for HIV, never the less that knowing how this guy looks like and what he likes we can deprieve him and then he dies if it doesn't get it.

I was so lucky that I had good friends that were already diagnozed for many years. I befriended them even though they told me when I met most of them they were HIV plus my best friend new the lives of every gay person in Miami (I was there at the time). I love them even though they were HIV. This particular one Bill Wallace, we even had condom sex once and we were attracted to each othe. What I didn't like was not his hiv and at the time there were no meds. It was his drug use. I don't mean pot. It was mainly cocaine. Everytime I stayed at his house it was peaceful and I felt like I was in my own place. But his drug use he hid from me became at time a little obvious. I hope when I die I see him coming to get me, where ever.... After I became poz and I know how where and by whom. I was a top so for me to aloud someone to top me I would take a lot of precautions and it only happned once every 5-10 yrs. I will put on the condome and it I was hurting, I will stop because I was afraid the condom will break. I never thought someone will take off the condom and fuck me wihtout it me thinking it was one, until in th emorning I found the condom, not used, no sperm inside. I asked this Brazilian visitor and he told me it fell off. Which a a lie. It wa a good thing he was a tourist. 2 months latter on my 6 months test I was poz. I fell apart. I even started telling coworkers and family, tying to get backing but that was a mistake. My friend Bill set me onthe right way and how to handle things. He would say Ive been poz for 10 yrs and even his partner died of it, it seems he gave tto Bill, Bill knew it but took care of him and then it was not pretty. When the hospital did not want you anymore you were sent home to die. With carcinoma and pneumonia and less than 100 pounds a man of over 6 ft. tall. But Bill taught me how to handle things. I got sick but my well kept tone body resisted bouts with pneumonia and eventually Crixivan came to be and saved us. To some it made them ugly with big bellies and humps but I would not aloud that.

Well That is my story, hope it helps you. I told you because 29 is young. No time is good to get a virus likemthis but at least you can have sex without giving it to someone and be healthy if you follow your regimen of mds. Good luck and Im here for you Mr. Handsome.

me :>)

2020 ~March

"New HIV Vaccine Fails but Not All is Lost They Tell us"

2019 Jan-Dec} Trending

Last posting for 2019 unless something comes up...don't hold your breath unless you can hold it for 2 or 3 years:

(Click or copy and paste)

https://adamfoxie.blogspot.com/2019/12/three-hiv-vacs-for-2021-all-you-need-is.html

Article

RW Eisinger, GK Folkers, and AS Fauci. Ending the HIV pandemic: optimizing the prevention and treatment toolkits. Clinical Infectious Diseases DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciz998 (2019).

Who

NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., is available for comment.

July 16, 2019:

News posted on the news part of this blog on 04/20/19:

* The-HIV-virus-used-to-cure-bubble-boy

* Researchers-say-single-injection-can-keep HIV at bay for 4 months

How about NOT every day dozing?

The meds for HIV we are using today are so strong that makes us "UNDETECTABLE" and if it doesn't show you can't transmit! They have studies about once a day dozing can be done every other day and the results are promising. Just don't make changes until you speack with your HIV Doctor. If you have a General Practitian make sure he or she are experts on the treatment of HIV. (Adam, Publisher of Adamfoxie)

HIV+ Undetactable individuals CanNot Transmit to a Negative Sexual partner

You will find different studies and these same headlines for the last two years on this page. That you heard that someone got Hiv from this one or that one is just hearsay. The only information that counts are studies in which the Doctors know everything about the subject and what they are presently doing. That is a study. Taking HIV meds for the HIV+ individual is not enough and many get confused about that little but very important detail. You must show that you are undetectable! This is the cure of HIV we have today and many are not using it. This should have ended stigma but it hasn't because mainly HIV people passing on information that is hearsay. Don't say anything if you re not 100% sure and as always send the person to the right place to get information. Another one: Not all doctors have studied HIV. ASK this page, read it here ask someone involved in HIV with a license. One more thing...How would you know if a person is undetectable? Ask for the latest tests. If he is truly undetectable he is being closely monitored and about every three months, there is a blood test to show where he is in this spectrum. If you are undetectable and don't get or ask or have readily available on your cell phone, etc the latest results where it gives you the number of virus you have, it has to say undetectable or not enough to count.

🦊Adam

Results from a new study presented at the 22nd International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam confirmed something HIV academics have suspected for a long time: The chance of an HIV-positive person with an undetectable viral load transmitting the disease to their partner is “scientifically equivalent to zero.”

These results came from a study known as PARTNER 2, which tracked 635 same-sex couples between May 2014 and April 2018 who were HIV serodiscordant at the start of the study — meaning one was HIV-positive and the other negative — and have condomless sex.

For couples where the HIV-positive person had an undetectable viral load — meaning their drug treatment suppressed the presence of HIV in their blood below 200 copies per milliliter — zero instances of HIV transmission between the couples occurred, according to AIDSmap. These results reinforce the validity of the slogan U = U, meaning “undetectable equals untransmittable.”

“You would have to have condomless sex for at least 420 years to have one incident of HIV transmission,” one researcher said at the conference, per Gay Star News.

The results of PARTNER 1, a study of 888 couples — most of whom were opposite-sex — that concluded in 2014, resulted in similar conclusions about the chance of HIV transmission between serodiscordant couples. However, questions lingered about whether anal sex and vaginal sex would have different chances of HIV transmission. Enter PARTNER 2, which tracked mostly same-sex male couples having condomless anal sex.

Notably, the HIV-negative participants in PARTNER 2 were not taking pre-exposure prophylaxis, a daily pill known as PrEP that reduces the chance of HIV transmission between serodiscordant individuals by more than 90%.

“We looked so hard for transmissions,” principal researcher Alison Rodger told AIDSmap. “And we didn’t find any.”

- An HIV vaccine tested in animals prompted the immune system to form antibodies that neutralize dozens of HIV strains.

- A small study of the test vaccine in people is expected to begin in late 2019.

Related Links

- Engineered Antibody Protects Monkeys From HIV-Like Virus

- Dual Antibody Treatment Suppresses HIV-Like Virus in Monkeys

- HIV Vaccine Progress in Animal Studies

- HIV Immunotherapy Promising in First Human Study

- The Structure and Dynamics of HIV Surface Spikes

- Making Antibodies That Neutralize HIV

- Antibodies Protect Human Cells From Most HIV Strains

- Insights Into How HIV Evades Immune System

- HIV/AIDS

Get it from the horse's mouth:

AIDSinfo - Official Site

More: https://adamfoxie.blogspot.com/2018/08/instead-of-keeping-it-like-secret-lets.htmlUndetectable-hiv-means Nontransmittable

|

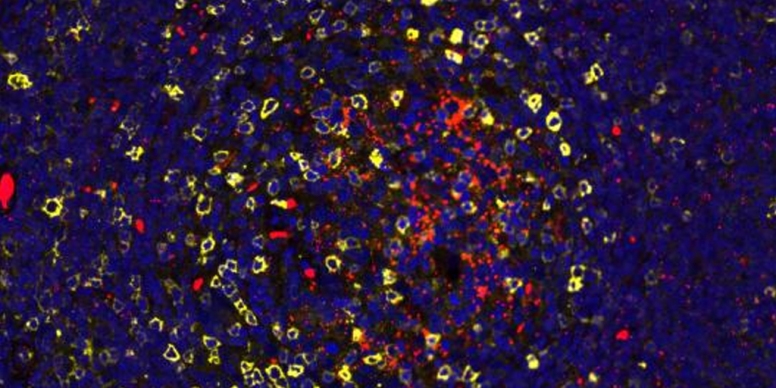

| Scanning electromicrograph of an HIV-infected T cell. |

What's Next? Viral Eradication.

Antibody isolated from people with HIV which can Neutralize Multiple Strains of HIV

Researchers have isolated antibodies from people living with HIV that can neutralize multiple strains of HIV. By studying these broadly neutralizing antibodies, they’ve gained important insights into how the antibodies bind to the virus and why they’re effective. Investigators from NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the pharmaceutical company Sanofi set out to create more potent broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies. The team was led by Dr. John R. Mascola, director of the NIAID Vaccine Research Center, and Dr. Gary J. Nabel, Sanofi chief scientific officer and senior vice president. The work appeared online in Science on September 20, 2017.

The researchers combined portions of individual broadly neutralizing antibodies to engineer a series of antibodies in the laboratory. They created dozens of “bispecific” (binding to two different sites on the virus) and “trispecific” (binding to three different sites) antibodies. Testing revealed the most successful to be a trispecific antibody that combined parts of the broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies VRC01, PGDM1400, and 10E8v4. This single engineered molecule interacts with three independent parts of the HIV surface.

Infusions of the three-pronged antibody completely protected eight monkeys from infection with two strains of SHIV, a monkey form of HIV. In contrast, infusions of the individual antibodies from which the engineered antibody was derived were only partially protective. The trispecific antibody also prevented a broader range of HIV strains from infecting cells in the laboratory.

Sanofi is manufacturing the trispecific antibody for use in a Phase 1 clinical trial that NIAID is planning to conduct. The trial will test the antibody’s safety and effects in healthy people beginning in late 2018. Discussions also are under way for a separate Phase 1 clinical trial of the antibody in people living with HIV.

“Combinations of antibodies that each bind to a distinct site on HIV may best overcome the defenses of the virus in the effort to achieve effective antibody-based treatment and prevention,” says NIAID Director Dr. Anthony S. Fauci. “The concept of having a single antibody that binds to three unique sites on HIV is certainly an intriguing approach for investigators to pursue.”

The ability of trispecific antibodies to bind to three independent targets could make them useful for other types of treatments as well. Other potential targets include infectious diseases and cancers.

July20: Meds Resistance Can Undermine HIV Battle

- Rising levels of resistance to HIV drugs could undermine promising progress against the global AIDS epidemic if effective action is not taken early, the World Health Organization (WHO) said on Thursday.

Already in six out of 11 countries surveyed in Africa, Asia and Latin America for a WHO-led report, researchers found that more than 10 percent of HIV patients starting antiretroviral drugs had a strain resistant to the most widely-used medicines.

Once a threshold of 10 percent is reached, the WHO recommends countries urgently review their HIV treatment programs and switch to different drug regimens to limit the spread of resistance.

HIV drug resistance develops when patients do not stick to a prescribed treatment plan - often because they do not have consistent access to proper HIV treatment and care.

Patients with HIV drug resistance start to see their treatment failing, with levels of HIV in their blood rising, and they risk passing on drug-resistant strains to others.

The WHO's warning comes as the latest data from UNAIDS showed encouraging progress against the worldwide HIV/AIDS epidemic, with deaths rates falling and treatment rates rising.

Some 36.7 million people around the world are infected with HIV, but more than half of them - 19.5 million - are getting the antiretroviral therapy medicines they need to suppress the HIV virus and keep their disease in check.

The WHO said, however, that rising HIV drug resistance trends could lead to more infections and deaths.

Mathematical modeling shows an additional 135,000 deaths and 105,000 new infections could follow in the next five years if no action is taken, and HIV treatment costs could increase by an extra $650 million during this time.

"We need to ensure that people who start treatment can stay on effective treatment, to prevent the emergence of HIV drug resistance," said Gottfried Hirnschall, director of the WHO's HIV and hepatitis program.

"When levels of HIV drug resistance become high we recommend that countries shift to an alternative first-line therapy for those... starting treatment."

The WHO said it was issuing new guidance for countries on HIV drug resistance to help them act early against it. These included guidelines on how to improve the quality and consistency of treatment programs and how to transition to new HIV treatments, if and when they are needed.

(by Kate Kelland, editing by Pritha Sarkar for Reuters)

Genetic Truvada Approved by FDA

In a move that has taken HIV advocates by considerable surprise, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a generic formulation of Gilead Sciences’ blockbuster antiretroviral (ARV) Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine). This decision could have major implications for the future cost of Truvada, to insurers and consumers alike.

The approval, which grants Teva Pharmaceuticals the right to produce generic Truvada, is for the combination tablet’s use as a component of an HIV treatment regimen and as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Generic Truvada will come in the same form as the brand-name version: as a fixed-dose combination tablet, although the famous powder-blue color may change.

“Yes, the first generic for Truvada has been approved and will now be available in the U.S.,” Jeffrey S. Murray, MD, MPH, deputy director of the Division of Anti-Viral Products at the FDA, tells POZ. “Usually, it takes several generics before full cost-savings potential is reached though. Hopefully, this will help to expand PrEP availability for many.”

According to Murray, it remains unclear what sort of exclusivity Teva may have to produce generic Truvada. Generic manufacturers often hold such exclusive rights for an initial period before competitors can also begin producing a particular generic medication and thus drive down prices. Murray stated that clarity on Teva's rights in this regard may not come for several months.

A Teva spokesperson confirmed the generic Truvada approval, but said that no further related information was available at this time.

“While this is stunning news that AIDS activists didn’t expect until 2021, I’m worried about the fallout,” says ACT UP and Treatment Action Group veteran Peter Staley. “Gilead’s patient and copay assistance programs have become central pillars in patient access. They must maintain these programs, and Teva must establish equivalent or better assistance programs for their generic version.”

More information on the implications of this approval is to come. Check this link later for updated information.

(Poz.com)

Condom-less Sex: A Doctor’s opinion

poz.com

Growing Old with HIV after Decades of Treatment

The success of breakthrough HIV drugs means one of the biggest challenges in the decades to come will be treating HIV as part of the aging process. More than half of all people with HIV in the United States are over 50, and by 2030 it is estimated that this figure will rise to 70 percent, according to the International Society for Infectious Diseases. Older HIV patients will be in general decline, while also battling conditions caused by decades of HIV drug use.

"This is a new frontier for a lot of us," said Kelsey Louie, chief executive officer at nonprofit Gay Men's Health Crisis. "People are living longer with HIV, so we are dealing with things we haven't had to deal with before, like the long-term effects of medication," he said. "It's important to understand that people who are aging will be facing other health issues that will only be complicated by HIV."

The economic toll of HIV in the U.S. keeps rising. This year federal funding for the disease has reached $27.5 billion. Today there are more than 1.2 million people in the United States living with HIV. More than 700,000 people with AIDS have died since the beginning of the crisis, according to data compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2014, there were 12,333 deaths (due to any cause) of people with diagnosed HIV infection ever classified as AIDS, and 6,721 deaths were attributed directly to HIV, according to the CDC. Doctors and drug companies are pursuing new approaches to treatment.

"We are at a fork in the road," said Greg Millet, vice president and director of public policy at AIDS nonprofit amfAR, who previously worked on AIDS and aging as a government epidemiologist during the Obama administration. "The fact that people living with HIV are living longer is fantastic news for many of us coming up in the era of the '80s and '90s, when it was effectively a death sentence and people did not live beyond five to 10 years," he said.

"When you are taking care of patients for their life, you don't want to only be able to offer them just one medicine. ... You have to take a long view and be able to switch medications whenever necessary."

-John Pottage Jr., chief scientific and medical officer at ViiV Healthcare

Eric Sawyer, age 62, a long-term HIV activist and consultant at the New York City-based GMHC, knows all too well the toll that these lifesaving medications can take on the body. Sawyer started developing symptoms of HIV back in 1981, even before the virus was discovered. At the time, he was told that he wouldn't live to see age 35. Fortunately, he was able to enroll in some of the earliest clinical trials taking place in HIV medical research. He has taken part in testing for a host of HIV drugs over the years.

While these drugs helped save Sawyer's life, some of the drugs he took came with debilitating side effects. One drug played a role in his developing peripheral neuropathy, which causes severe pain in his feet. To this day, Sawyer can't wear regular shoes. Years later Sawyer developed avascular necrosis of the hip. "My hip started to crumble, and I had to have a hip replacement in my 40s and the other hip replaced a couple of years ago."

The development of this type of necrosis can arise from the use of anabolic steroids that physicians often prescribe to people living with HIV to help them to gain weight, or from medications currently being prescribed to treat the disease, said Dr. Bisher Akil, a New York City-based physician who treats Sawyer.

About five years ago Akil started Sawyer on an antiretroviral medication called Truvada, developed by Gilead Sciences. Today's HIV antiretroviral drug regimens are taken in pill form, as part of a three-drug treatment regime that work together as a cocktail to block the HIV-virus at different parts of the replication cycle. This approach stops the virus from infecting new cells and allows a patient's T-cell count to replenish. These drugs have proven so successful they can reduce the amount of the HIV virus detectable in the body to a degree that it is no longer measurable by a blood test.

Truvada worked well for Sawyer, but the medication may also have played a role in causing a severe level of toxicity in his kidneys, which left untreated can result in renal failure. To stop the elevation of serum creatinine levels in Sawyer's blood, which was causing damage to his kidneys, Akil took Sawyer off Truvada and replaced it with Gilead's newer version of the drug, Descovy, which received the Food and Drug Administration's approval in April 2016.

Descovy, a combination of the drugs emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), can be given at a much lower dose than Truvada. Several of Gilead's newer HIV drug therapies, such as Genvoya and Odefsey, contain TAF in place of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which is the main ingredient in Gilead's older HIV drugs — Stribild, Atripla and Complera, as well as Truvada.

TAF has demonstrated that it works as well as TDF-based drugs at less than one-tenth the dosage. It has also demonstrated improvements in renal and bone safety. Patients in a trial on a TAF-based drug had less hip and spine bone loss and more favorable kidney function than those on TDF-based drugs, according to Gilead.

Descovy has an average wholesale price of near-$1,800 a month, similar to Truvada's price, according to pricing information from the National Institutes of Health. Sawyer's doctor said paying for Descovy would be cheaper for the health insurance provider than paying for Sawyer to go on dialysis or get a kidney transplant, which is where Sawyer was headed. After six months on Descovy, Sawyer's kidney function improved.

This switch to newer drugs is beginning to show up in Gilead's results. In its quarterly earnings released last week, overall HIV drug sales increased by 12 percent, to $3.4 billion, in the fourth quarter 2016, even as Truvada sales and sales of other, older TDF-based HIV drugs continued to decline. HIV sales totaled $12.9 billion for the full year 2016, also up from the previous year's level of $11.1 billion.

Accelerated aging

AmfAR's Millet said HIV and related drug therapies have been shown to accelerate the aging process with issues including the onset of kidney and liver disease, bone loss and osteoporosis and cognitive impairment.

"We need to start focusing on these other issues. … There is not enough medical literature on common geriatric drugs and HIV drugs," he said. Millet added that the issue is not only whether HIV drugs and other geriatric drugs could interact negatively but whether other drugs could suppress the HIV drug regimen. There is also evidence that HIV-positive individuals develop an immune system that is described as "hyper vigilant" for an extended period of time, and in older people that can lead to chronic inflammatory conditions.

ViiV Healthcare is close to releasing new HIV medications that could do less harm to older HIV patients by replace the three- and four-drug "cocktail" many HIV patients are on with a two-drug therapy. The UK-based joint venture of Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline and Japan's Shionogi & Co. released Phase III clinical trial results this week for one of its new two-drug therapies.

John Pottage Jr., chief scientific and medical officer at ViiV Healthcare, said two drugs is the lowest number needed to inhibit the virus at different parts of its replication cycle. "If you are thinking about patient care over the long term, you want to be able to individualize the care of patients and provide for future options that may come with less side effects," he said. A two-drug therapy may do just that. "It goes back to having choices for patients," Pottage said.

UNAIDS: We're making progress but prevention is still a challenge UNAIDS: We're making progress but prevention still a challenge

Wednesday, 30 Nov 2016 | 9:06 PM ET | 02:21

Pottage said the prognosis for these new therapies is promising and the company expects to file with the FDA for approval in mid-2017. If all goes well, ViiV Healthcare will bring at least one two-drug HIV-treatment combinations to market in 2018, per FDA approval. The company will be filing in other countries and regions around the world as well.

ViiV is also working with Johnson & Johnson's Janssen to develop a once-a-month injection for patients who have already achieved HIV-viral suppression through a daily pill regimen.The injectables would be given as an intramuscular shot that releases the medication out into the body over a period of time, a dramatic change in the way antiretroviral treatment is administered. The pharma company has started a Phase III trial and will evaluate the data in 2018 with the hope of submitting it for FDA approval in 2019.

Global sales of HIV therapies reach into the tens of billions of dollars.

Competition between drug developers remains fierce, but Pottage said that all new discoveries are welcome, in particular by physicians. "When you are taking care of patients for their life, you don't want to only be able to offer them just one medicine. You may need to change the medications and dosage to see which drugs are more tolerable," Pottage said. "You have to take a long view, and be able to switch medications, whenever necessary."

Millet agreed. "Providing choices of drugs is one of the best ways to suit what is best for patients," he said. For some that may be to continue taking a daily dosage of pills. But cognitive impairment could make it more difficult for older HIV patients to manage their prescriptions, creating a need for a delivery option, like injectables.

The young and the old

Millet said research into long-term injectables would help the HIV population on both ends of the demographic curve: the youngest HIV-positive individuals are by far the largest group of new cases, as well as undiagnosed cases.

The annual number of new HIV diagnoses in the United States from 2005 to 2014 declined by 19 percent, but as many as 50,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, according to CDC data. Thirty-seven percent of new HIV cases in 2015 were among people age 13 to 19, according to the CDC. Sixty-three percent of new HIV cases are among individuals 29 years or younger.

"This would be very helpful for young people, as they are less likely to adhere to medication," Millet said. It would not only help young HIV patients to suppress the virus but would reduce the number of new cases. Millet said there is also ongoing research into HIV drug implants, which could function similar to birth control and work for as long as a year.

"Younger individuals did not experience the period of the HIV epidemic in which people with HIV were dying in great numbers due to a lack of treatment options. This can make it difficult to communicate the urgency of HIV prevention efforts."

-Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, assistant commissioner of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control at the NYC Health Department Control

In New York City the number of new HIV diagnoses has decreased in all age groups over the past five years, and that means that everyone living with HIV is living longer, said Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, assistant commissioner of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control at the NYC Health Department.

"The overall epidemic is aging because of population dynamics," Demetre said, but he added that new HIV diagnoses are indeed concentrated among young persons. In 2015, 36 percent and 26 percent of new diagnoses in New York City were among persons age 20 to 29 and 30 to 39, respectively.

Younger individuals "are still the leading edge of the epidemic – where the most sexual activity is taking place and where the lowest levels of viral suppression have been achieved," he said. Sixty-six percent of all persons 20 to 29 are virally suppressed, whereas 86 percent of persons over the age of 60 are virally suppressed.

"These factors create the 'perfect storm' for the ongoing epidemic among younger persons," Demetre said. "Younger individuals did not experience the period of the HIV epidemic in which people with HIV were dying in great numbers due to a lack of treatment options. This can make it difficult to communicate the urgency of HIV prevention efforts."

"Long-term injectables are incredibly promising," Millet said. But he stressed one point about current HIV drugs that should not be lost as research into new drugs proceeds: "The first-line medication are easily the best ever. These are remarkably effective, with very few side effects."

— By Leslie Kramer, special to CNBC.com

The Other Brain in HIV Infection (the other brain refers to the Gut)

- Zdenek Hel, Jun Xu, Warren L. Denning, E. Scott Helton, Richard P. H. Huijbregts, Sonya L. Heath, E. Turner Overton, Benjamin S. Christmann, Charles O. Elson, Paul A. Goepfert, Jiri Mestecky. Dysregulation of Systemic and Mucosal Humoral Responses to Microbial and Food Antigens as a Factor Contributing to Microbial Translocation and Chronic Inflammation in HIV-1 Infection. PLOS Pathogens, 2017; 13 (1): e1006087 DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006087

If you are Undetectable and have been for a year non stop then you should feel free. I understand for some only a blood test that says “cured” would be the only thing to make them feel free but things particularly in medicine with an ever mutating virus do not tend to go by those rules. You need to be informed. The following is a story of a man that went through all the cycles an HIV person goes through but then felt free after being Undetectable:

Who can a zeroNegative guy be safe with? Discordant partners can feel so much better with what we’ve known about meds and becoming undetectable:

HIV-positive people with a viral load below 200 copies/mL while on antiretroviral therapy (ART) did not transmit HIV to steady sex partners during more than one year of condomless sex in the European PARTNER Study. Eleven HIV-negative partners, including 10 men who have sex with men (MSM), did become infected during follow-up, but phylogenetic analysis did not link the infecting virus to their on-treatment partner. Confidence limits and short follow-up so far suggest, however, that "appreciable levels of risk cannot be excluded."

HPTN 052 and other studies showed that HIV-positive people with ART-suppressed viremia have an exceedingly low risk of transmitting HIV to their sex partners. To determine transmission risk from virally suppressed HIV-positive European partners having vaginal or anal sex, the PARTNER Study Group conducted this prospective observational analysis.

From September 2010 to May 2014, researchers recruited HIV-discordant partners (one HIV-positive, one negative) at 75 clinical sites in 14 European countries. To be included in the transmission analysis, partners had to report (1) condoles vaginal or anal sex in the months before enrollment, (2) continued condomless sex during the study period, (3) no use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and (4) latest viral load in initially positive partner below 200 copies/mL on ART.

Negative partners were tested for HIV infection every 6 to 12 months, while positive partners had their viral loads tested at the same intervals. If a negative partner acquired HIV infection, viral pol and env sequences from both partners were tested to determine whether the partners' HIV was genetically related.

The transmission analysis involved 888 couples, including 548 heterosexual couples and 340 MSM couples. Among heterosexual couples, 279 (51%) had an HIV-positive female partner and 269 a positive male partner. Median ages of MSM and heterosexual men and women ranged from 40.1 to 44.9 years. About 80% of participants were white. Median follow-up measured 1.3 years per couple and overall follow-up totaled 1238 couple-years. Among HIV-negative partners, MSM reported a median of 42 condomless sex acts per year, heterosexual men reported 35 and heterosexual women reported 36.

During follow-up, 11 initially negative partners acquired HIV infection, including 10 MSM and one heterosexual. Eight of these 11 people reported recent condomless sex with someone other than their regular partner. HIV sequence analysis found no evidence indicating that newly infected partners acquired HIV from their study partner.

HIV transmission rate from positive to initially negative partners was 0 for MSM and for heterosexual men and women. The rate was 0 for vaginal sex, insertive anal sex and receptive anal sex with ejaculation. Upper 95% confidence limits for certain subgroups were higher than the overall upper 95% confidence limit of 0.30 per 100 couple-years for any sex, for example, receptive anal sex with ejaculation in MSM (2.70) or heterosexual women (12.71) and insertive anal sex in heterosexual men (7.85).

Although the transmission rate for vaginal or anal sex was 0, the PARTNERS investigators cautioned that "95% confidence limits suggest that with eligible couple-years accrued so far, appreciable levels of risk cannot be excluded." The researchers stressed that their results "cannot directly provide an answer to the question of whether it is safe for serodifferent couples to practice condomless sex."

Still, despite the median follow-up of 1.3 years per couple, the authors noted that their analysis "contains more than 3 times the couple-years of follow-up for condomless sex than all the other previous studies combined, including more than 500 couple-years of follow-up of condomless anal sex."

Mark Mascolini writes about HIV infection, {The Body}

No Proof of New HIV Cure, Despite Headlines -- Here's What We Know

Whenever you see a newspaper headline about a cure for HIV, it's worth treating it with a pinch of salt. That's certainly the case with the latest story, first reported by The Sunday Times of London and repeated in media outlets around the world.

Many people living with HIV desperately want to see a cure for HIV. Millions of other people would be fascinated and encouraged to see such scientific progress. Journalists know this, which is why they so often fall into the trap of writing stories that suggest a cure is just around the corner. The idea fills us with hope, and huge numbers of people will click on the story to find out more.

The mainstream media tends to report these issues in a misleading way or leave out key details that would help people living with HIV understand what the developments mean for them. Important and legitimate scientific studies are misrepresented.

What's the New Story About a Cure?

The headlines tell us "British Scientists on Brink of HIV Cure," "HIV Cure Close After Disease 'Vanishes' From Blood of British Man" and "British Man Becomes the First Patient Cured of HIV."

The reports suggest that the man took an experimental treatment and now the scientists cannot find a trace of HIV in his body. That suggestion is wrong. Here's what really happened.

He was diagnosed within six months of infection and took an intensive treatment regimen -- four antiretrovirals, a drug called vorinostat and two vaccines.

Several months after beginning his treatment, tests can't detect HIV in his blood. In other words, his viral load result is undetectable. This may sound remarkable and astonishing to some journalists, but people with HIV will know that this is exactly the result we expect after several months of antiretroviral therapy.

Remember, this man's treatment includes antiretroviral therapy, the same drugs used by other people living with HIV. He took other, innovative treatments as well, but his antiretroviral therapy alone could be expected to bring his viral load down to an undetectable level.

And, very importantly, he is still taking antiretroviral therapy. Nobody knows what will happen if he ever decides to stop taking his treatment.

What Do We Know About the Study?

The man is taking part in a serious clinical trial that is investigating an innovative approach to treating HIV. Researchers at five leading British universities are conducting it.

The scientists hope their aggressive treatment will eradicate latent reservoirs of HIV in the body. Reservoirs are made up of millions of immune system cells that contain dormant HIV. They persist even when antiretroviral treatment reduces viral load (RNA) to undetectable levels -- but would be re-activated if antiretroviral treatment were stopped.

Around 50 people who have had HIV for less than six months will take part in the study. They will all take an intensive combination of antiretroviral therapy (four drugs, including Isentress [raltegravir]).

In addition, half the participants will be randomly assigned to take the innovative treatments. For one month, they will be given vorinostat, a drug that forces the virus to emerge from hiding places in the body. They will also receive two vaccines that aim to boost the immune system so that it can attack HIV-infected cells. The strategy is called "kick and kill."

Ten months after study participants enter the trial, the researchers will measure levels of HIV DNA in CD4 cells. This will provide an indication of whether the treatment has had an impact on the HIV reservoir.

The unnamed man who has been the focus of the media attention is simply the first study participant to have completed the experimental therapy. The researchers report that the treatment was safe for him. In a brief statement they released on Oct. 3, the researchers themselves note that results of the study will not be reported until 2018, and that until then, "We cannot yet state whether any individual has responded to the intervention or been cured."

Questions and Answers

‘What about the other people taking part in the study?

‘Only 39 of about 50 participants have been recruited so far. We don't know anything else about the other participants.

‘Do tests show that this man's viral reservoir has been eliminated?

‘We don't know; the scientists will only report this information when the trial is completed in 2018.

‘How would we know that someone is cured of HIV?

‘Antiretroviral therapy would have to be stopped and the person monitored for several years. Researchers would check to confirm that either that there was no trace of HIV in any cells or the person's immune system could keep HIV under control without treatment.

‘Will people in this trial stop their antiretroviral therapy?

‘This is not part of the study. The researchers may explore this option in the future but are not recommending it for now.

‘Has anything like this been tried before?

‘Slightly different "kick and kill" approaches have been tried in other studies. And there have been examples of people taking intensive treatment very soon after infection, continuing with it for several years, then stopping treatment and remaining undetectable.

‘Has anyone been cured of HIV?

‘To date, there is only one confirmed case of an HIV cure. Timothy Ray Brown, who needed treatment for advanced leukemia, received a never-before-attempted stem cell transplant in which the donor had a rare mutation making him essentially immune to most forms of HIV.

Thebody.com

Does Undetectable means Un-infectious?

It’s a profound mental, cultural and social shift to acknowledge that people with HIV who are undetectable can have condomless sex with HIV-negative people without transmitting the virus.

- An increase in condomless sex among people with HIV who are undetectable will lead to an increase in STIs; and

- People with HIV might not understand that staying on treatment is essential to maintain an undetectable viral load. For instance, they might interrupt treatment by personal choice or due to circumstances outside of their control and unknowingly experience an increase in viral load and risk of HIV transmission.

- Depending on the drugs employed it may take as long as six months for the viral load to become undetectable.

- Staying undetectable requires excellent adherence to treatment.

- Having an undetectable viral load prevents only HIV, not other STIs or pregnancy. Condoms protect against HIV as well as other STIs and pregnancy.

- Many people with HIV may not be in a position to reach undetectable because of various challenges related to access to treatment (for example, poor health care systems, poverty, denial, stigma, discrimination, criminalization) or antiretroviral toxicities, or they may not be ready or willing to start treatment. There are many barriers to testing, treatment and long-term adherence outside the control of people living with and vulnerable to HIV that must be addressed.

THE END OF AIDS? PBS special report on HIV/AIDS

SUPER ANTIBODY OFFERS POTENTIAL TREATMENT, CURE

Scientists have isolated potent HIV antibodies — immune system fighter proteins targeted specifically against the virus — that have implications for the prevention and even destruction of the virus that causes AIDS.

The powerful, broadly neutralizing antibodies are produced by an extremely small, “elite” group of HIV-positive individuals. The antibodies have kept them alive and in some cases thriving for many years without the use of antiretroviral drugs.

Scientists have harnessed these super antibodies, which recognize and disarm many different strains of HIV, and have mass-produced them with the aim of giving them to normal HIV patients.

Using the latest technology to cull and replicate the most potent antibodies, researchers tested the neutralizing proteins in a group of 13 individuals. All of the participants had been on antiretroviral drugs for a long time.

Antiretrovirals suppress HIV, but don't kill certain cells that act as reservoirs and harbor the virus. That means the virus can roar back to life when the drugs are stopped, in a process called viral rebound.

Writing in the journal Nature, the researchers said that among people who did not receive the new antibody, called 3BNC117, viral rebound occurred in about two and a half weeks. Those who did receive it were able to delay rebound by as long as almost 10 weeks in some cases.

'Kick and kill'

Michel Nussenzweig of Rockefeller University in New York, a corresponding author of the study, said 3BNC117 might one day be able to destroy the virus that causes AIDS.

“People have thought for a long time that one way to think about a cure strategy would be to do something called 'kick and kill' — that is, to activate the viruses that are in the latent reservoir and then use an agent like an antibody, for example, that would be able to see the activated cells that are starting to produce the virus and kill them,” Nussenzweig said.

Nussenzweig and colleagues are planning experiments using a cancer drug that unmasks the virus hidden in reservoir cells, and then killing them with 3BNC117.

One of the benefits of the antibody is that it doesn’t seem to have any side effects, according to Nussenzweig.

“They were made originally by human beings and we have not modified them at all," he said. "So they are completely natural products and should not have major side effects. In fact, the people who received them so far — and it’s a small number — have not reported any significant problems.”

Nussenzweig said a large clinical trial in Africa, using a similar neutralizing antibody developed by the vaccine center at the National Institutes of Health, is underway to see whether injections of the protein can protect women at risk of infection.

voanews.com by

(Jessica Berman)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Intravaginal Ring Loaded with Tenefovir

An intravaginal ring loaded with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF, Viread) provided mucosal tenofovir concentrations high enough to protect against ex vivo HIV challenge in a 14-day placebo-controlled trial that enrolled healthy women. Product-related adverse events were all grade 1.

TDF with or without emtricitabine has proved effective as oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in women and men. The high tissue and cell penetration of TDF and its long intracellular half-life make it a good candidate for intravaginal ring administration, which could promote better adherence than daily or as-needed oral or gel TDF. Also, TDF retains anti-HIV activity in the presence of seminal plasma. A TDF intravaginal ring completely protected macaques from 16 weeks of intravaginal simian SIV challenge.

U.S. academic researchers recruited 30 healthy, sexually abstinent women 18 to 45 years old and randomized them after cessation of menses in a 1:1 ratio to insert a polyurethane reservoir intravaginal ring bearing TDF or to insert a placebo ring. Participants gave blood and vaginal swab samples on study days one, three, seven and 14, and they removed rings on day 14. They provided additional samples two to four and seven days after ring removal. Researchers also collected an ectocervical biopsy on day 14 for pharmacokinetic analysis and rectal swabs on days seven and 14.

Advertisement

Age averaged about 29 years in study participants and body mass index about 25 kg/m2. One woman withdrew from the study. Rings remained in place for 14 days in all other women, all of whom reported it was very easy or somewhat easy to wear.

Researchers recorded 29 adverse events in 12 women randomized to the TDF ring and 14 adverse events in seven women randomized to placebo. Eight events judged to be product related occurred in six women randomized to TDF and in one randomized to placebo. All product-related events involved cervical or vaginal discharge and were grade 1. There were two nonproduct-related grade 2 adverse events and no grade 3 or 4 or serious adverse events.

The TDF ring provided high tenofovir disoproxil (TFV-DP) and tenofovir concentrations in cervicovaginal fluid (CVF) from the vagina, ectocervix and introitus within one day of insertion, and concentrations remained high through day 14. After ring removal, median initial tenofovir half-life in CVF from the vagina, ectocervix and introitus stood respectively at 14, 12 and 11 hours. Median tenofovir concentrations remained above 1000 ng/mL two to four days after ring removal, a finding suggesting that the ring could protect women who remove the device before sex.

Median tenofovir and TFV-DP concentrations in ectocervical biopsies collected on day 14 were respectively 5.4 ng/mg and 120 fmol/mg. Rectal tenofovir could be measured in five of five participants who agreed to anoscopy on day seven and in four of five on day 14. Median CVF vaginal-to-rectal fluid ratio was 104 on day seven and 240 on day 14.

An ex vivo model using T cells challenged with HIV-1 in the presence of CVF collected from the cervix indicated 29% median inhibitory activity at enrollment, 96% inhibitory activity on day seven and 94% inhibitory activity on day 14.

The researchers conclude that the TDF ring "is safe, well tolerated, and results in mucosal tenofovir concentrations that exceed those associated with HIV protection." On the basis of their results, the authors “anticipate that the ring will continue to deliver ~5-6 mg/day of TDF for 30-45 days and will result in very rapid steady state tissue TFV-DP concentrations that exceed those achieved following oral TDF PrEP in adherent women, but with significantly lower systemic concentrations, thus avoiding potential toxicities."

Mark Mascolini writes about HIV infection.

TheBodyPRO.com

By Myles Helfand

From TheBodyPRO.com

This week, we got our first published glimpse of how the new tenofovir stacks up against the old tenofovir after two full years of first-line therapy. We were also given a first look at what a long-acting form of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) might do for rates of HIV infection and mortality among high-risk populations -- and what it might cost. Plus, we were given a critical new resource to help improve HIV testing and outreach among trans people. To beat HIV, you have to follow the science!

First-Line Therapy Comparison: TAF vs. TDF at Week 96

At 96 weeks, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) continues to keep pace virologically with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF, Viread) in treatment-naive people with HIV, while exhibiting a superior toxicity profile, according to study results published in the May 1 issue of the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes.

The study summarizes the findings of two Phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that randomized 1,733 antiretroviral-naive volunteers to receive elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine coformulated with either TAF or TDF. After two years on the study drugs, there was no significant difference between the percentage of people with a viral load below 50 copies/mL who received TAF (86.6%) and those who received TDF (85.2%), with virtually no emergence of resistance among those whose therapy failed in either arm. However, marked differences were noted between the two drugs on the toxicity front.

Advertisement

"With TAF, there are smaller declines in bone mineral density and more favorable changes in proteinuria, albuminuria, and tubular proteinuria, and no cases of proximal tubulopathy compared with 2 for TDF," the study authors noted. In fact, differences in bone mineral density widened between weeks 48 and 96 despite increased usage of drugs to improve bone density among TDF recipients, they stated. The authors also commented on a continuation of more favorable renal markers among TAF recipients relative to TDF recipients in the span between week 48 and week 96.

"Together, these longer-term safety data support the hypothesis that circulating levels of TFV [tenofovir] are responsible for the bone and renal toxicity of TDF and that the markedly reduced TFV level delivered by TAF minimizes such exposure and is protective against renal and bone effects," the researchers conclude.

Potential Value of Long-Acting PrEP for South African Women at High HIV Risk

The eventual use of long-acting antiretrovirals for PrEP will probably prevent more HIV infections among high-risk South African women than the current PrEP standard regimen, but at greater financial cost, according to the results of an extensive computer simulation by researchers in the U.S. and South Africa.

Appearing in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the study, led by Rochelle Walensky, M.D., M.P.H., of Massachusetts General Hospital, calculated the comparative cost and effectiveness of three PrEP strategies implemented among a simulated cohort of young South African women (mean age 18). Using an extensive array of existing study data to inform their models, the researchers sought to generate reasonable estimates of the impact of no PrEP, standard PrEP (using existing oral formulations) and long-acting injectable PrEP on lifetime HIV risk and five-year mortality, as well as the cost-effectiveness of each approach.

The simulation found that, after an average of eight years of PrEP use, reasonably effective (75%) long-acting PrEP reduced lifetime HIV incidence among the virtual cohort by 19% compared to no PrEP (510 cases per 1,000 high-risk women, compared to 630); by comparison, reasonably effective (62%) standard PrEP reduced lifetime HIV incidence by 14% over eight years compared to no PrEP (540 cases per 1,000 high-risk women). Within five years, long-acting PrEP would avert 156 new HIV infections and 16 deaths, while standard PrEP would avert 127 new HIV infections and 15 deaths, the model predicted.

Although both PrEP approaches were deemed to be cost-saving relative to the use of no PrEP at all, standard PrEP was found to be the least expensive over the course of a cohort member's lifetime, at US$5,270 total (compared to the slightly higher $5,300 for long-acting PrEP, and the sharply higher $5,730 for no PrEP, which included the costs of HIV care and antiretroviral therapy for the greater number of women who would become infected). Long-acting PrEP program implementation was found to have a much higher ramp-up cost than standard PrEP implementation, but a lower cost afterward.

"The delivery of existing oral PrEP formulations, which are very cost-effective, should be expanded and optimized for young, high-risk South African women," the researchers concluded. In addition, they urge that "the research and development effort should be expanded to bring a viable [long-acting] PrEP formulation to market."

UCSF Releases Transgender HIV Testing Toolkit

- What is PrEP?

- I have an STD. Why all the questions from my doctor?

- Why would I take PrEP if I don't have HIV?

- Does my sex life put me at risk for HIV?

- Do I have other risk factors for HIV?

- Do I have to use condoms if I take PrEP?

- Will PrEP keep me from getting other STDs?

- What can I do if I think I need PrEP?

- Find the article at http://education.webmd.com

- Breaking in Aug.The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first-ever diagnostic test that differentiates between types of HIV infection.The Bio-Rad BioPlex 2200 HIV Ag-Ab assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, Hercules, California) distinguishes between HIV-1 antibodies, HIV-2 antibodies, and HIV-1 p24 antigen in human serum or plasma specimens. It is intended for use with the BioPlex 2200 System, which was cleared by the FDA in 2004.HIV-1 is the most commonly found type around the world. HIV-2 is found primarily in West Africa but has also been identified in the United States. The two viruses are similar, but distinct. Differentiating between the types is important for patient care because they progress at different rates, said Karen Midthun, MD, director of the FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a news release.The new assay allows results of antigen and antibody detection to be reported separately. Because HIV antigens and antibodies appear and are detectable at different stages of the infection, reporting of the distinct results helps differentiate between acute and established HIV infection, according to the FDA.The Bio-Rad BioPlex 2200 HIV Ag-Ab assay can be used in adults, children aged 2 years or older, and pregnant women. It may also be used to screen organ donors for HIV-1/2 when the blood specimen is collected while the donor's heart is still beating. However, the assay is not approved for use in screening blood or plasma donors, except in urgent situations where traditional, licensed blood-donor screening methods can't be used.

July 2015

If Not a Cure then Permanent Remission

Why? “Because the reservoir of cells is not only in the blood,” the Nobel Prize winner explained. “How to eliminate all the cells which are reservoirs is why I say it’s an impossible mission. They are everywhere—in the gut, in the brain, in all the lymphoid tissue.

“Even if you have a very efficient strategy,” she continued, “how you can make sure that there’s not one or two cells still there and if one is there the virus will reappear again? That’s why I say it’s an impossible mission. But you never know.”

She was speaking about a sterilizing cure, which is when the virus is completely eradicated. This compares with a functional cure, in which the virus is under control without meds.

When asked about a functional cure, Barré-Sinoussi said, “I prefer to say remission (when the virus is brought down to low levels in the body) … That’s possible. I’m convinced one day—I don’t know when—we will have a strategy to induce durable remission. I don’t believe that we will have only one treatment. It will be a combination of treatments. (But) we need both—a cure and a vaccine.”

Barré-Sinoussi spoke with CNN during the 8th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention in Vancouver, British Columbia. She is a former president of the IAS, and she is also retiring next month because “in my country it’s mandatory to retire.”

Something of a lone, and ferocious, wolf in the public opposition to PrEP, Weinstein has tinkered with his stance over time as increasing scientific evidence has supported Truvada’s use as a tool to fight the spread of HIV. Currently, he claims not to be against PrEP, saying that he maintains a “nuanced” position by arguing that Truvada may be a worthy option for some individuals, but should not be used as a broad public health intervention.

“Mass PrEP administration is a dangerous experiment that is not supported by medical science and is currently resisted by doctors and patients alike,” he claims in the ad.

Instead, he believes that the best way to prevent HIV transmission is through behavior modification and condoms, as well as through testing for the virus and treating people with HIV in order to render them vastly less infectious. This is a standpoint that dovetails neatly with his position as the leader of the world’s largest provider of treatment for the virus, with more than 420,000 patients in 36 countries.

Fact check:

- Claim: Behavior modification, while never 100 percent effective, has been a remarkable success with gay men.

- This is definitely true when you look at the entire history of the U.S. HIV epidemic. In the 1980s, the use of condoms and other forms of behavior modification among American gay men were highly successful in reducing what was initially a soaring rate of HIV infection in that population. However, in recent years, as memories of the horrors of the early AIDS crisis have faded and a new generation rises that never knew those days, gay men have increasingly shifted their sexual behavior in the opposite direction. Condom use has decreased among the population while the HIV infection rate has risen once again.

- Claim: The ad implies that those supporting PrEP advocate giving up on condoms.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which recently has become a strong advocate for PrEP, encouragesusing condoms with Truvada. However, there are certainly PrEP advocates who have quite publicly celebrated Truvada as a tool by which to enjoy condomless intercourse.

- Claim: Truvada has not caught on with medical providers or patients.

- Weinstein relies on Gilead Sciences’ report that only 5,272 PrEP prescriptions were written through 2014. There are many limitations to that estimate that make it a highly unreliable barometer for PrEP use in the United States. It is based on approximately 39 percent of U.S. retail pharmacies and less than 20 percent of Medicaid data, and does not include the many gay men receiving PrEP through a study.

- Research suggests that approximately 4,000 San Franciscans are taking PrEP. In New York State, PrEP prescriptions filed through Medicaid rose 272 percent between June 2014 and February 2015, from 305 to 832. A recent POZ survey found that various medical providers across the country have seen dramatic increases in prescription rates over the past two years. About 400 people currently receive PrEP form the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City.

- Claim: 95 percent of HIV medical providers are “concerned that their patients would not adhere” to the daily Truvada regimen.

- This refers to a survey of members of American Academy of HIV Medicine, which the AAHIVM published in April. Indeed, 95 percent of the 324 respondents said that “concerns about adherence” to Truvada were “very important” when deciding whether to prescribe PrEP. However, as physicians have argued since Weinstein began publicizing this figure, it is only natural that a clinician should be concerned that patients will not adhere to any drug. This figure, therefore, does not necessarily imply grave reservations about PrEP in particular.

- In the same survey, 79 percent of the clinicians said they were “very likely” to prescribe PrEP to MSM having sex with an HIV-positive partner, while 66 percent said they were very likely to prescribe to MSM at risk for contracting HIV.

- Claim: Every published study of PrEP has shown major efficacy problems. For example, the largest study among MSM (iPrEx) had “only a 42 percent efficacy.”

- By limiting this claim only to published research on PrEP, Weinstein leaves out the results of both the PROUD and IPERGAY studies, which each showed an effectiveness rate of 86 percent among MSM. (Effectiveness, which refers to a drug’s actual, across-the-board success, is the correct term; efficacy only refers to a drug’s potential for success.) PROUD studied PrEP among very high-risk MSM in the United Kingdom and was designed to reflect real-world use of Truvada. IPERGAY tested an intercourse-based dosing protocol of PrEP in which MSM participants in France and Canada were instructed to take Truvada only in the days surrounding a potential HIV exposure.

- The iPrEX study and its open-label extension (OLE) phase, the two published studies of PrEP among MSM, had respective effectiveness rates of 44 percent (not 42 percent) and 50 percent. Weinstein has long characterized these rates as failures. On the contrary, these figures can and should be viewed as successes: The trials succeeded at lowering the rate of HIV by a considerable amount among the high-risk participants taking Truvada. A true failure would have been if PrEP increased or led to no change in HIV rates, or perhaps if the risk reduction was too small to justify a PrEP roll-out. Weinstein also omits the fact that the U.S. participants of the OLE trial adhered at a much higher rate than their international counterparts, suggesting that they enjoyed a greater benefit from PrEP than the study group as a whole.

- Claim: “In the most successful of all the published studies [on PrEP] more than half of the patients did not take the medication as directed.”

- According to AHF spokesperson Christopher Johnson, this claim refers to the Partners PrEP trial, which studied PrEP among heterosexual couples in Kenya and Uganda and had a 67 percent success rate. Since the study did not include MSM, its results are not particularly relevant to a gay male audience.

- Johnson backed up AHF’s claim about the lack of adherence in Partners PrEP with the fact that an estimated 55 percent of the study’s participants had at least one gap of 72 consecutive hours of nonadherence. However, the same analysis showed that just 23 percent of the participants had at least one weeklong adherence gap. According to the head of Partners PrEP, Jared Baeten, MD, PhD, a professor at the University of Washington School of Public Health, Weinstein’s assertion that the study’s participants were highly nonadherent is a “very skewed” interpretation of the research. More than 80 percent of the participants, Baeten points out, had detectable study drug in their blood and 70 percent had concentrations consistent with daily use. Additionally, Baeten states that the Partners PrEP substudy that looked at the adherence gaps measured daily pill-taking through the use of an electronic pill bottle, and that 72-hour gaps may reflect people not taking PrEP while risk was low (perhaps while not having sex) or taking out multiple doses for use while traveling.

- Claim: Those in the Partners PrEP study who were most at risk were also the least likely to adhere properly.

- AHF’s Christopher Johnson refused to provide a citation for this claim. University of Washington’s Jared Baeten asserts the claim is false. He and his colleagues have conducted a number of analyses to determine what factors affected adherence in Partners PrEP (a study which, again, did not include MSM), and found that a consistent factor linked with lower adherence was not having sex. This suggests that, in fact, being low risk was linked to low adherence, and, conversely, that higher risk people adhered at higher rates.

- In iPrEx OLE, the higher-risk participants were more likely to opt to start PrEP in the first place (those who chose not to take Truvada served as a control group), and were then more likely to adhere.

- Claim: Not-yet-published European research on intermittent (also known as intercourse-based) PrEP use among MSM has shown very high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and poor adherence.

- The IPERGAY study indeed showed a very high rate of STIs among the MSM participants—35 percent of the participants contracted one during the study—which is indicative of the fact that they were at high risk for HIV, and therefore good candidates for PrEP. There was no evidence that men increased their sexual risk taking during the study, so PrEP itself cannot be blamed for those STIs.

- With an 86 percent effectiveness rate, the dosing strategy in IPERGAY was actually a great success, indicating that adherence was quite good. It is not clear whether the specifics of the protocol itself led to such a high risk reduction or just the fact that the men wound up taking PrEP often enough to enjoy a significant risk reduction regardless of the exact timing of the pill taking. (The iPrEX OLE results suggest that taking Truvada four times a week offers maximum protection against HIV.) The two participants given Truvada who did contract HIV had apparently stopped taking PrEP several weeks before becoming infected.

- Claim: Concerns about the effectiveness of PrEP in the clinical trials would be “nonexistent if the patients wore condoms.”

- PrEP is most strongly urged for MSM who are already not using condoms. In a perfect world, all those men would use latex for every potential exposure to the virus. PrEP acknowledges the reality that these men may not be willing or able to change their behavior, but that they may indeed have the capacity to follow a drug regimen that will lower their risk.

- PrEP’s HIV risk reduction benefits can complement those of condoms; the two prevention techniques are not mutually exclusive, and indeed are often used together.

- Claim: According to the CDC, three out of four MSM used condoms during their last sexual encounter.

- True, but highly misleading. The same 2011 CDC report states that, out of 8,000 MSM in 20 U.S. cities, 57 percent reported having anal sex without a condom during the previous year.

- Claim: “The entire body of scientific data demonstrates that Truvada will not be successful as a mass public health intervention.”

- The PROUD study strongly suggests otherwise: It examined PrEP’s use among high-risk MSM in a real-world setting and had an 86 percent success rate.

- Claim: Weinstein insinuates that “the condom culture that has been so hard fought since the [beginning] of AIDS” will disappear.

- This is a worthwhile concern to raise. At this time, none of the studies of PrEP among MSM support the notion that Truvada will lead to a reduction in condom use among that population. However, anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise: that PrEP may indeed contribute an already dropping rate of condom use among MSM. It is possible that one of the reasons that men in the PrEP studies don’t use condoms less while on Truvada is that they already weren’t using them much to begin with; being at high risk for HIV is a qualification for entry into the studies.

- Claim: The condom is the most effective prevention method for an individual who has multiple partners or whose partner has multiple partners.

- If an individual gay man takes PrEP daily, Truvada's 99 percent or greater effectiveness likely offers superior protection against HIV than regular condom use. (And of course he may use condoms in addition to Truvada.) It’s very hard to pin down exactly how effective condoms are when used for anal sex; research is scant, and a recent CDC paper claiming condoms are only 70 percent effective when used consistently and correctly by MSM is based on highly questionable reasoning. But in a nutshell, it’s simpler to use Truvada correctly—you swallow a daily pill—than condoms. Condoms may fail due to putting them on wrong, improper lubrication, or not keeping them on for the entire act of intercourse, a common practice. Psychologists have also argued that it is easier to adhere to a drug that is taken as a part of a daily routine than it is to use a condom during moments when that sense of personal responsibility may be challenged by sexually and emotionally charged experiences.

- Weinstein’s argument here seems to contradict his claim in the previous paragraph that “Truvada can absolutely be the right decision for specific patients.”

- Claim: If everyone with HIV in the United States knew their status, went on treatment and had an undetectable viral load, there would be no new HIV infections.

- This sweeping claim is categorically false because of the impossibility of alerting everyone to their HIV status the instant they contract the virus. During the first few months of infection, viral loads tend to be very high, making an individual highly infectious. Additionally, acutely infected individuals may be engaging in the same high-risk behaviors that led them to contract the virus in the first place, allowing them to transmit the virus to others before they are tested. Estimates vary, but scientists believe a considerable proportion of new HIV cases transmit from people recently infected with the virus.

- Furthermore, as Weinstein points out in the ad, just 30 percent of Americans living with HIV currently have an undetectable viral load. So his vision of treating our way to zero HIV transmissions is a long way off, to say the least. In the meantime, the scale-up of PrEP among high-risk populations will hopefully help reduce infection rates, in particular among MSM.

A-vaccine-for-hiv-and-therapy-duo.html

Inflammation and gut leakage remains elevated in people with HIV despite early antiretroviral treatment

| In order for viruses to reproduce, they must infect a cell. Viruses are not technically alive: they are sort of like a brain with no body. In order to make new viruses, they must hi-jack a cell, and use it to make new viruses. Just as your body is constantly making new skin cells, or new blood cells, each cell often makes new proteins in order to stay alive and to reproduce itself. Viruses hide their own DNA in the DNA of the cell, and then, when the cell tries to make new proteins, it accidentally makes new viruses as well. HIV mostly infects cells in the immune system. Infection: Several different kinds of cells have proteins on their surface that are called CD4 receptors. HIV searches for cells that have CD4 surface receptors, because th |

End of HIV?

New Lab Fabricated Protein Kills of the Mutants of the HIV Virus

|

| David Duran |

Well, you most likely won't be surprised by the reactions from the haters and skeptics to this monumental news. This news has been long-awaited by those who know their positive status, are taking medication and are taking care of themselves. Is it a license to be reckless? No, but it is a reassurance that treatment as prevention does work.

As someone who happens to be HIV positive, my major fear regarding the disease is passing it on to someone else. My second fear is the rejection I could possibly face with disclosure. Do I disclose before being intimate? If a partner asks me upfront, I am always honest right back, and when the topic is left up to me to bring up, I'd say that I do initiate the conversation the majority of the time. But in the back of my head, I always would reassure myself that my viral load is undetectable and most likely would not be putting anyone at risk. With this landmark finding, is it possible that everyone, especially gay men, will be more inclined to get tested, know their status and be upfront and open about it all the time?

In a perfect world, everyone would get tested, know their status, and take the appropriate steps thereafter. The shame and stigma that surround HIV would diminish, and the world would go on as normal, and HIV would be controlled and the spread of the virus contained. Having an undetectable viral load would be sexy. Knowing your status and getting tested regularly would be, well, regular. Being HIV positive and having an undetectable viral load would be considered the same thing as being HIV negative. Instead, we would frown upon those who don't know their status. Being HIV positive and having an undetectable viral load would be accepted, especially within the gay community.

So will all this happen overnight? Will Grindr or other dating apps see an increase in gay men changing their status to say, "Undetectable as of..."? In this dream scenario, HIV-positive people who are on treatment and taking care of themselves by maintaining an undetectable viral load would feel more empowered to come out and show everyone their A-plus report card each time they have their labs done, wearing those test results with honor and being proud for being healthy.

Unfortunately, unless those of us who are HIV positive become more open about our status and stop hiding behind the stigma, things most likely won't change overnight. We can all already hear the naysayers with the release of the first two years of this second study. And at the same time, we shouldn't automatically ditch the condoms or all our safe-sex practices. As we all know, there is a world of other communicable infections.

What I hope will not happen is for HIV-positive people with undetectable viral loads to hide behind these results and live life as if they were HIV negative. Not being able to transmit the virus is the only thing the two types of individuals have in common. An undetectable viral load is not to be used as a justification for not disclosing your status before engaging in unprotected sex. Instead, these results should build up your confidence so that you can be more open about your HIV status and, if you are HIV positive, keep up on maintaining your undetectable viral load as well as being healthy.

The more we open up and discuss what it means to be HIV positive with an undetectable viral load, the more society, especially those within our own community, will begin to understand, learn and accept. With advancements in antiretroviral therapies, attaining and maintaining an undetectable viral load is not difficult, especially if treatment is started immediately after learning of a positive HIV status.