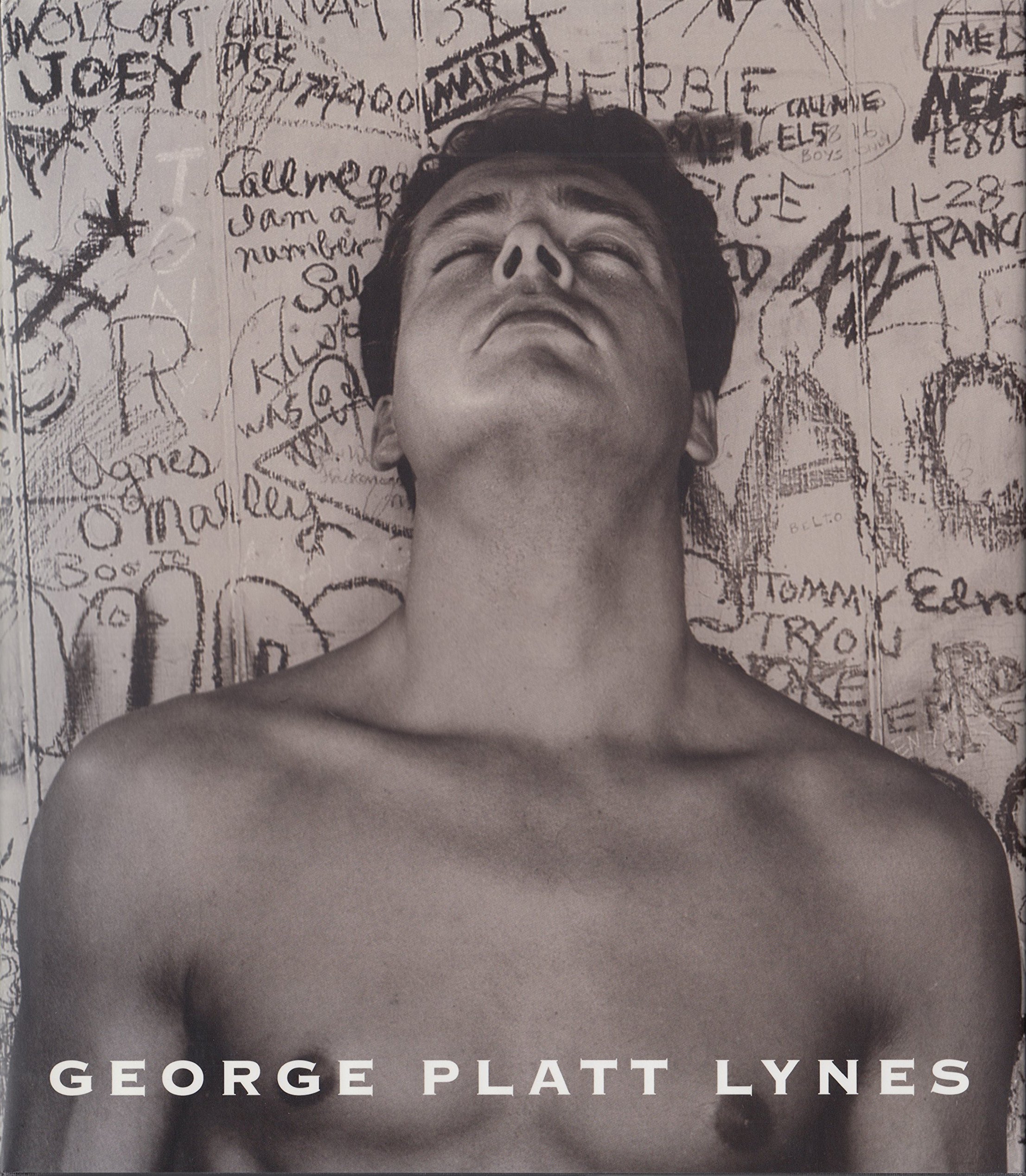

The forgotten Legacy of Gay Photographer George Platt Lynes

From the late 1920s until his death in 1955, George Platt Lynes was one of the world’s most successful commercial and fine art photographers.

His work was included in one of the first exhibitions to showcase photography at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, and he showed at the extremely popular Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. His photographs for Vogue and Bazaar, his shots of dancers at the School of American Ballet and his portraits of some of the most important creative figures of his era were lauded for their innovative use of lighting, props and posing.

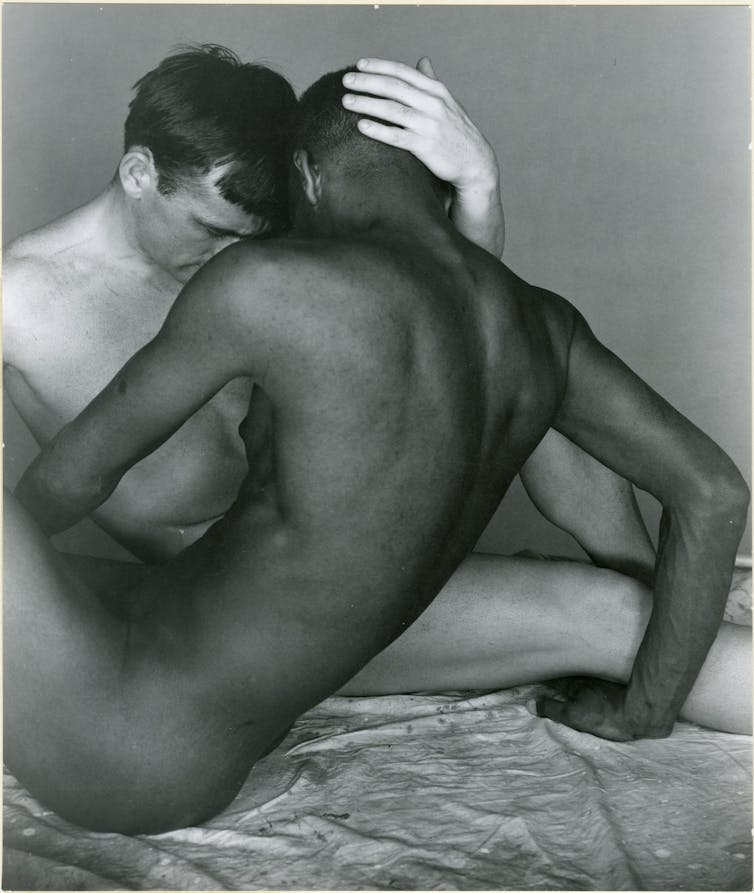

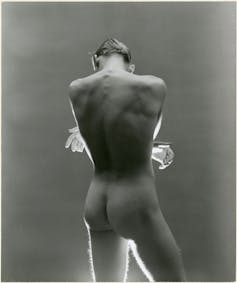

But in his view, his most important works were his nude photographs of men. Yet during Lynes’ life, few even knew of their existence.

Because of prevailing attitudes toward homosexuality, which included criminalization and strict obscenity laws, Lynes – himself a gay man – had to keep this incredibly influential and important body of work hidden away.

These nuanced photographs of the male form ended up sparking a friendship between Lynes and Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey, the founder of the Institute for Sex Research, later renamed the Kinsey Institute, at Indiana University. Upon his death, Lynes gifted over 2,300 negatives and 600 photographs to the Institute for Sex Research.

The dynamic between Lynes’ commercial and fine art photographs, along with the relationship between Lynes and Kinsey, is the subject of a new exhibition I recently co-curated at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields titled “Sensual/Sexual/Social: The Photography of George Platt Lynes.”

On view through Feb. 24, 2019, the exhibition features many pieces that have never been displayed before. They fill a gap in art history and serve as a window into a time in American culture when gay men like Lynes faced obstacles to unfettered self-expression.

Groundbreaking photography

George Platt Lynes was born in New Jersey in 1907 and attended the Berkshire School in Massachusetts, graduating in 1925.

As a young adult, Lynes had a passing interest in photography, but his dream was to be a writer: he published a literary journal called The As Stable Publications and opened up a bookstore in New Jersey. Neither endeavor proved fruitful, so when he happened to inherit a studio’s worth of photographic equipment from a friend, he decided to focus on photography as a career.

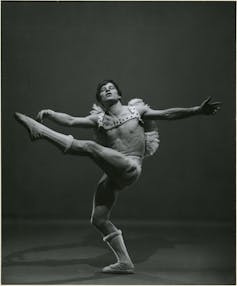

One of Lynes’ friends from his Berkshire School days was Lincoln Kirstein, who had recently co-founded the School of American Ballet with choreographer George Balanchine. Lynes and Kirstein became reacquainted and Lynes became the primary photographer for the school, later to be called the New York City Ballet, for 20 years.

Beginning with his ballet photography, Lynes would follow an impulse to upend established norms.

Whereas most photographers would take photos of dancers during their performances, Lynes would take photos of the dancers off-stage, often bringing them to his studio. He wanted to encourage the viewer to focus on the interplay of light, shadows and the body. These images are considered to be some of the finest ballet photographs ever taken.

“I consider that George Lynes synthesized better than anyone else the atmosphere of some of my ballets,” Balanchine wroteafter Lynes passed away. “[His] pictures will contain, as far as I am concerned, all that will be remembered of my repertory in a hundred years.”

Lynes’ fashion photographs were no less groundbreaking. He started photographing for fashion magazines in 1933 to supplement his income. But through his innovative use of props and lighting, he soon found himself one of the most sought-after photographers in the industry.

Inspired by Surrealists, Lynes would juxtapose seemingly disparate ideas and objects to create something new. He posed models in odd, sometimes humorous settings. In one image, included in the exhibition at Newfields, Lynes has placed a basket full of hay and birds atop the head of a model who wears a glittering, beautifully tailored dress, and displays her perfectly manicured nails.

Lynes often shot fashion spreads in his apartment in Manhattan, which was lavishly decorated and provided a more personalized atmosphere than photographs shot in a studio. Lynes was also a master darkroom manipulator, working with his negatives and prints to achieve the look he wanted.

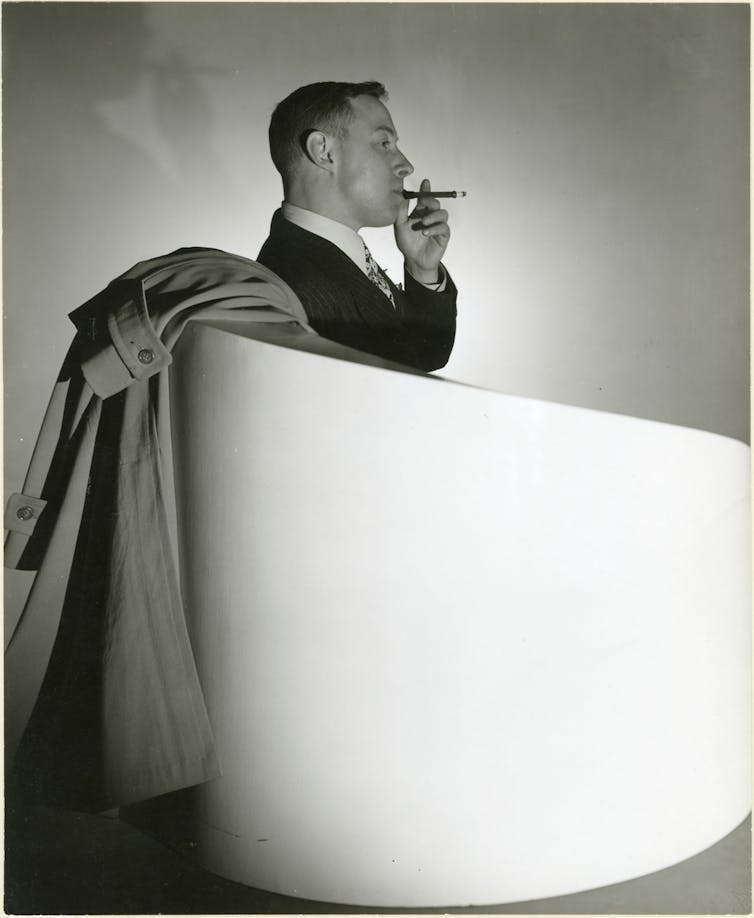

Portraiture was another of Lynes’ specialties. Lynes had an active social life, and was known for throwing lavish parties that were attended by the stars of the avant-garde.

He was able to capture in his photographs some of the most influential creative people of his time, including writer Tennessee Williams, artist Marc Chagall and composer Igor Stravinsky. He did so with great attention to detail, using props and creating individualized sets for his subjects.

Lynes’ true passion

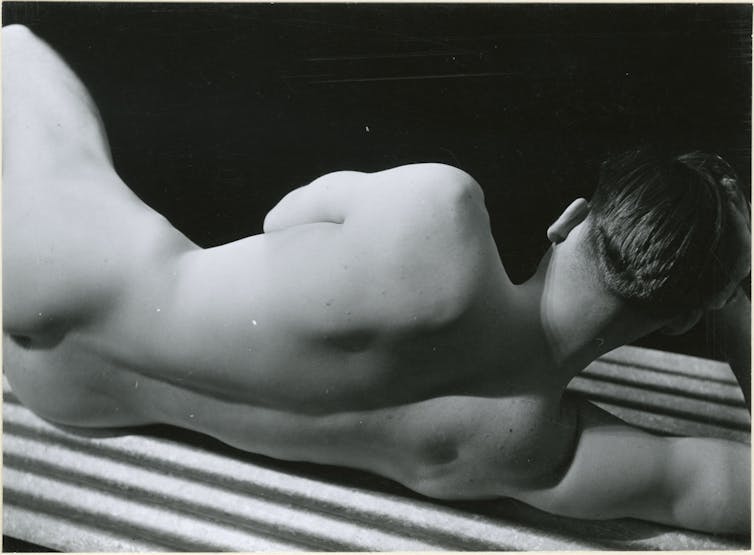

Yet all along, Lynes had been taking photographs of the male nude.

The naked male form has long been represented in fine art, mostly appearing in religious, athletic or classical contexts. Lynes’ interest in Greek classical representation of the male body – especially his focus on musculature – grounded his male nude photos in an accepted aesthetic tradition. But Lynes’ photographs also present the male form as beautiful and desirable, adding a completely new element of homoeroticism.

Lynes’ models included his friends, lovers and studio assistants. Some were professional paid models, including a young Yul Brynner, who posed for photographers and drawing classes in New York to make ends meet.

Lynes took considerable risk in photographing the male nude and his models also faced a number of potential repercussions.

After World War II, there was an increase in policing and crackdowns on LGBTQ communities. If he publicly exhibited these works, he might compromise his ability to get commercial work and could face criminal penalties.

But he also identified this body of work as his favorite. “I’ve done my best work when I’ve worked only for pleasure, when I’ve not been paid, when I have a completely free hand, when I’ve had a model who has excited me in one way or another,” he wrote to his partner, Monroe Wheeler, in 1948.

A friendship forms

In the late 1940s, Dr. Alfred Kinsey had just published “Sexual Behavior in the Human Male” and was busy building his collection of material culture related to human sexuality.

Kinsey first learned of Lynes’ work through writer Glenway Westcott. Westcott, Monroe Wheeler and Lynes had been in a ménage à trois relationship for many years, and Westcott thought that Lynes’ images of male nudes might be of interest to Kinsey.

Kinsey began corresponding with Lynes about acquiring his photos, and over the years the two men developed a friendship. Lynes was grateful for Kinsey’s work to normalize the diversity of human sexuality. He was thrilled to play a small part: “The big interest of the moment is Kinsey – in all our lives,” he wrote to his mother in 1949. “I had a three hour interview with him last Sunday … discussing artists, the erotic in art, and suchlike. … It’s an extraordinary job he is doing.”

The Comstock Act, which criminalized the sending of “obscene” materials through the United States Postal Service, was still in effect. So sometimes Kinsey would travel to New York, where Lynes was living, to transport the materials by hand. Other times, they would use private, expensive shipping companies to ship the materials.

When Lynes was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1955, he thought about his legacy and destroyed some of the negatives and prints from his commercial work. He wanted the work that he would be best known for to be the work that was also the most meaningful to him, which were his male nudes.

Kinsey offered the Institute for Sex Research as a possible repository for his work. Lynes was adamant about keeping his models’ identities confidential so they wouldn’t suffer any repercussions for posing nude, and Kinsey agreed. Today, the Kinsey Institute holds the largest collection of Lynes’ work outside of the Lynes estate.

Lynes had a unique command of formal aspects of photography – especially lighting – that made him an innovative technical artist. His choice of subject matter was pivotal to his aesthetic, which remains evocative and timeless. Presenting all of his subjects with dignity, grace and compassion is one of the most enduring aspects of his legacy.

Subsequent generations of photographers acknowledge how important Lynes is to the history of photography. But because of the times in which he lived – and the way he hid the work that he was the most proud of – his name became less familiar to the general public.

Through the preservation of his work by the Kinsey Institute, and the exhibition at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Lynes’ photographs will be seen and understood as the important and influential body of work that it is.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Comments