Gay Rights in Your Country

With the U.S. Supreme Court set to rule this month on the issue of same-sex marriage, CNN Opinion approached gay rights activists and leaders in other countries to get their view of the situation in their own societies.

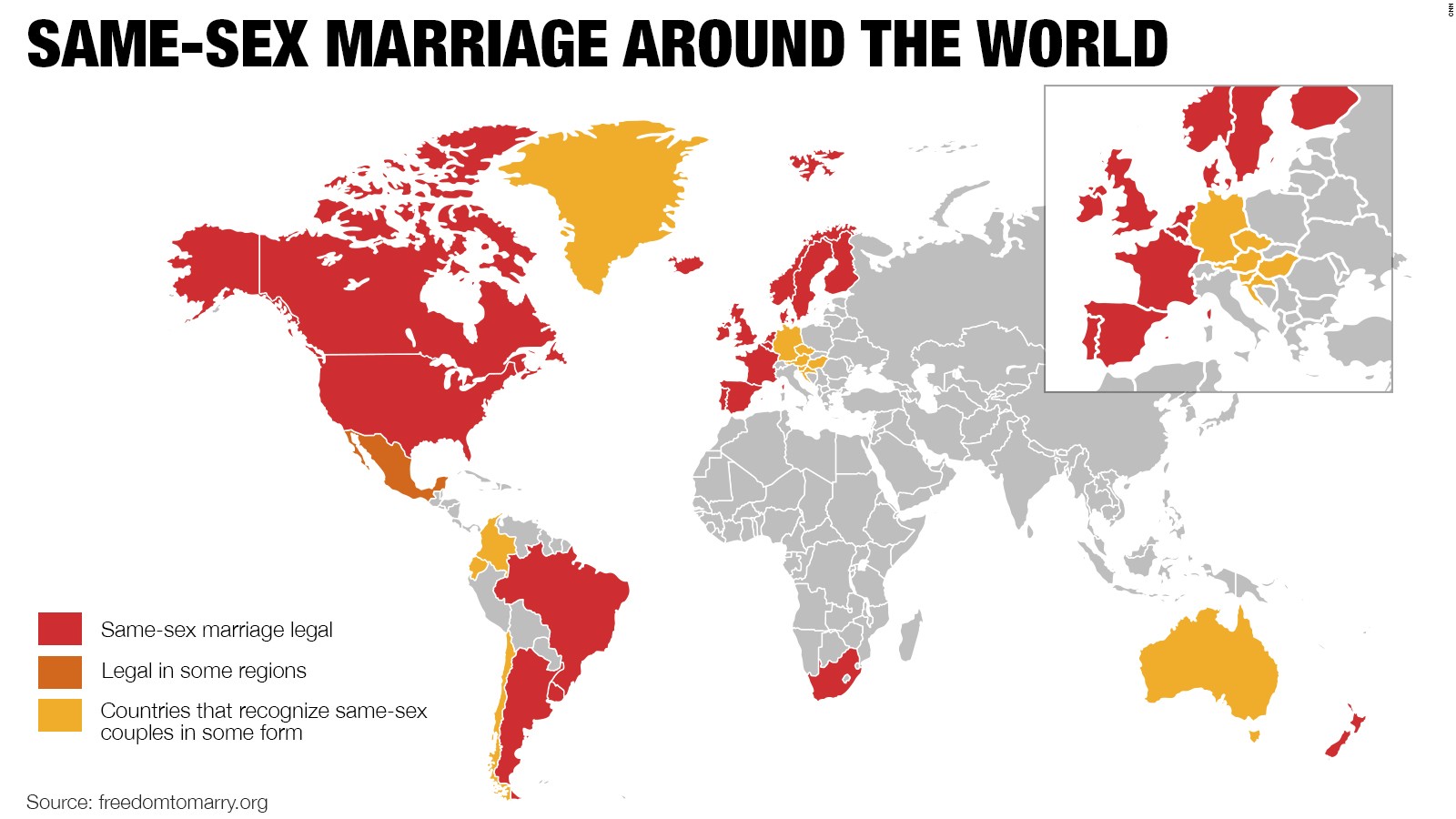

According to Pew Research, the view of same-sex marriage has shifted dramatically in the United States in the past 14 years -- from 57% opposed in 2001 to 57% now saying they are in favor. But Pew has also found that, across the globe, majorities in many countries still believe that society should not accept gay relationships.

Of those countries surveyed, the strongest support for acceptance of homosexuality came in Europe -- especially Spain (88% believe it should be accepted) and Germany (87%) -- and Latin America. In the Middle East and Africa, in contrast, clear majorities in all but one nation believed homosexuality should not be accepted, including South Africa, where same-sex marriage is legal.

The responses in our roundup -- which included countries and regions ranging from Colombia to southern Africa to Singapore -- showed a similarly diverse range of views on how same-sex relationships are viewed, and the question of whether things are getting any better for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities.

But no matter the country or continent, one theme ran consistently through all the contributions: However far legal recognition or public acceptance has advanced since 2001, when the Netherlands became the first country to legalize same-sex marriage, they believe there is still a long way to go.

All views expressed are the writers’ own.

The Netherlands

Philip Tijsma is public affairs manager at COC Nederland, a Dutch organization for LGBT men and women.

On April 1, 2001, the Netherlands became the first country in the world to open civil marriage to same-sex partners -- the highlight of an era marked by a long-running fight for equal rights in this country. Since then, more than a dozen countries have followed suit.

Philip Tijsma:

Yet despite this success, it's also obvious that equal rights enshrined in the law do not necessarily lead to equal treatment in society. Indeed, while some may think of the Netherlands as some sort of “gay paradise," and although it is true that much has been achieved, the truth is that the layer of acceptance in this country is thinner than many may think.

For example, one poll showed that 1 in 3 Dutch people thinks it's offensive to see two men kissing in public, compared with 1 in 10 for a straight couple. Meanwhile, about 7 in 10 LGBT people say they have been confronted with physical and/or verbal violence because of their identity. Plus, many LGBT students have a difficult time in high school, are bullied and see suicide rates that are almost five times higher than average.

As a gay man living in Amsterdam I have experienced much of this myself: being called a “dirty faggot" on the street, having beer cans thrown at me, and not hearing a word about the subject of homosexuality in the liberal high school I attended.

With this lack of acceptance in mind, the focus of the Dutch movement has shifted from equal rights to equal treatment and acceptance of lesbian women, gay men, bisexuals and transgender people in our society. A recent highlight in this fight is that the Dutch government in 2012 introduced the understanding of respectful treatment of LGBT people as a compulsory subject in all primary and secondary schools.

In the meantime, we keep advocating for equal rights. The Netherlands, for example, has no laws explicitly protecting transgender people from discrimination, which is one of the reasons the country has sunk to seventh place in the equal rights ranking of the European LGBT organization ILGA.

Thus the fight for equality continues, because whether it is social acceptance or equal rights for LGBT people, there is still much to fight for in the first country to introduce marriage equality.

Hong Kong

Tommy Chen is spokesman for Rainbow Action in Hong Kong:

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in Hong Kong continue to face alarming levels of discrimination and harassment in society, a reality not helped by the fact that there is no legislation that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Meanwhile, the government continues to ignore recommendations from United Nations treaty bodies and numerous civil society groups for legislation to protect the LGBT community in Hong Kong.

Tommy Chen

This matters, because discrimination is still very much a reality here.

One study, conducted by the Women Coalition of HKSAR (Hong Kong Special Administrative Region) in 2010, found that more than 50% of LGBT respondents had experienced discrimination, which actually marked an increase from a previous study conducted in 2005, in which 39% said they had been discriminated against. Meanwhile, research by the University of Hong Kong Public Opinion Programme found that 79% of the Hong Kong working population believed that LGBT individuals face discrimination or negative treatment.

As a result of the ongoing discrimination, the demand for sexual orientation discrimination legislation has been growing in the past few years. Almost 9,000 people marched last November in support of anti-discrimination legislation for LGBT people. And they seem to have backing among the public at large — a survey conducted by the Equal Opportunities Commission in 2012 found that 60% of the public supports legislation against discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Yet even though a majority of the public -- as well as the majority of the representatives in the Legislative Council -- supports this kind of legislation, the government continues to resist proposing any. And, because Hong Kong is not a regular democracy, legislation can only be proposed by the government, not by individual lawmakers.

Our best hope for change, then, is to urge the international community to send a clear message to Hong Kong's government to end sexual orientation discrimination. It is time that our leaders rose to the standard that is expected of an international city.

Canada

Nancy Ruth is a Canadian senator from Ontario.

Some big things have changed for women and lesbians in my lifetime in Canada. Others, like violence, have hardly changed. I do not see the world through LBGT eyes. I see it through the eyes of a woman. Being a lesbian is my second level of discrimination.

Nancy Ruth

L, B, G and T are different communities -- communities in a big, diverse and complex world of communities. We deserve to be treated as such, not lumped together as "Other."

Over the past 30-plus years in Canada, women and LBGT communities in Canada have made legal gains. Canada adopted a constitutional Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1985. It has offered a degree of substantive and formal equality for the disadvantaged. I look to the Charter to ensure that people achieve equality in their day-to-day lives, as Canada guarantees affirmative action in its Constitution.

In 2005, Canada became the fourth country in the world to legalize same-sex marriages. We forgot to fix our divorce legislation so that those who had married here could divorce here! We’ve fixed that now.

When I came of age in the 1950s and 60s, there were few spaces I could go to be safe as a woman and as a lesbian. That remains the case today for many women, for many lesbians. We have been formally accommodated, both in the mainstream and in gay culture, but not fully included.

Economic, social and cultural realities, like all aspects of violence, remain gendered and racialized. We spend vast amounts on the ISIS war on terror, but not on the war on terror against women and girls, the violence in the next room, street or town. Now the buzz is that because sex and gender are a matter of personal choice, across a spectrum and fluid, we have no use for sex and gender. I do not believe this. Sex is determined at birth with a DNA pattern. Gender fluidity is a matter of personal choice.

Ultimately, through these changes, I remain committed to laws, communities and spaces that address widespread and deep discrimination against women in all of their diversity.

United Kingdom

Lord Chris Smith of Finsbury is a member of Britain's House of Lords and a former secretary of state for culture and media under a Labour government.

When I first came out 30 years ago -- as the first ever openly gay MP in the United Kingdom -- there was ferocious inequality and a huge amount of discrimination. An unequal age of consent. A prohibition on "promotion" of homosexuality. No equality in the armed services, in the diplomatic or civil service, in access to goods and services, or in the recognition of partnership. LGBT rights were used as a political weapon by the Conservative Party. And there were regular denunciations of any sort of gay equality in the rabid parts of the tabloid press.

Chris Smith

How things have changed since then. All inequalities in law have been swept away. A Conservative government has helped to put equal marriage on the statute book. And even the tabloids have — albeit grudgingly -- celebrated the first gay marriages.

It's been one of the most rapid and remarkable stories of social change in recent history. Partly, that's been because a Labour government systematically picked off one bit of discrimination after another and changed the law. But even more importantly, it's because society has changed. People everywhere have realized that they have friends, neighbors, work colleagues, people they admire on television, even perhaps MPs, who just happen to be LGBT. And they are just as good, as valuable, as likable and as effective as anyone else. And it’s because social attitudes have changed that the law has been able to change too.

In recognizing difference and diversity, we've moved from prejudice, to tolerance, now to acceptance, and we're moving toward celebration. We’re not there yet, but we're moving fast in the right direction.

Dominican Republic

Guillermo Peña is a lawyer and political scientist in the Dominican Republic. He is the coordinator for the Human Rights Observatory for Vulnerable Groups in Santo Domingo.

Sadly, discrimination and violence are still a part of life for an alarming number of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people in the Dominican Republic. And, despite some promising recent legal reforms, a survey conducted last year found almost three-quarters of Dominicans believed the country discriminates against LGBT people.

Guillermo Pena

One of the problems here is the widespread lack of knowledge on human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity among police officers. A report published by the Human Rights Observatory for Vulnerable Groups(Observatorio de Derechos Humanos para Grupos Vulnerabilizados), for example, noted that the head of the country’s police force had said publicly that he would not accept homosexuals in the force.

This view, he argued, was consistent with article 10 of Law 285-66, which prohibits sodomy between police officers of the same sex. Yet this very law runs contrary to the Dominican constitution and international treaties signed by the country.

Meanwhile, trans workers in the Dominican Republic are still stigmatized and face frequent discrimination. For example, one recent study documenting the experiences of 90 trans sex workers in the two largest Dominican cities, Santo Domingo and Santiago, found that 42% of respondents had been verbally abused on the streets while they worked. Indeed, one passerby said to an interviewee, "Someone bring me a gun to kill this 'bird'" (an insult used to refer to homosexuals in the country).

If things are to change, and if LGBT people are to be able to live without fear of threat, then the Dominican state will have to pursue anti-discrimination legislation. Human rights are for everyone — and the state must ensure the law reflects that.

Colombia

Maria Mercedes Gomez is the regional coordinator for Latin America and the Caribbean of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission.

Colombia's Constitutional Court has taken some important steps in guaranteeing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex rights. From decisions on civil unions, social security and protections for intersex children to the adoption of the biological child of a domestic partner, the country's top court has provided legal recognition of LGBTI rights.

Maria Gomez

Earlier this year, for example, the court handed down a landmark decision on trans rights, telling Colombia's army that it could not compel trans women to serve in the military. The case was a breakthrough for trans women, who had typically been treated as male for military service purposes and compelled to get the military passbook for accessing basic rights. In spite of these advances, the petitioner in the case, Gina Vanesa Hoyos Gallego, is aware that dropping this requirement to serve is merely one of many obstacles she has to face to be fully recognized as a citizen.

More recently, on June 5, the Colombian President signed Decree 1227, which authorizes citizens to change their sex on identification documents and ends a long-standing element of discrimination. This decree ends the insecurity faced by transgender people of being misrecognized by the state and having to live with the criminalization and insecurity of not having the basic identification documents that others are guaranteed. With this decree, which was promoted by the Colombian ministries of the Interior and Justice, and with the help of Aquelarre, a coalition of trans organizations and civil society allies, trans people can finally have their ID changed to the sex with which they identify, rather than sex they were assigned at birth.

Yet despite these gains, state and nonstate violence continues to affect LGBTI communities. Much more work remains to be done, and Colombia will need to see a transformation in both the country's political and cultural practices to ensure these recently introduced rights are fully implemented.

LGBTI groups and individuals in Colombia have come a long way in gaining a political voice and recognition. Our hope is that one day, all Colombians will be able to enjoy their rights in peace, safety and with dignity, regardless of their sexual orientation and gender identity.

Singapore

Bryan Choong is the executive director of Oogachaga Counseling and Support in Singapore.

"I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it." -- Nelson Mandela

Bryan Choong

In a society that is less than fully accepting of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, coming out can be fraught with fear, and triumphing over that requires a certain amount of courage. After all, coming out can mean rejection from one's family, friends and community. Some end up losing their home or the opportunity to receive the education or job that they want.

Sadly, this is still the reality in Singapore. But that doesn’t mean there aren't brave men and women pushing for change.

In 2006, 15 people publicly revealed their personal stories and photos in the book "SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century." The following year, 100 more defied the Botanic Gardens' ban on holding a Pink Picnic on its grounds to celebrate LGBT diversity. Subsequently, more than 1,000 signed the parliamentary petition to repeal Section 377A of the Penal Code, a law that criminalizes consensual sex between adult men, even in private.

All these examples point to an emerging reality: that the momentum for the community to mobilize and become more visible has been growing. In 2009, 2,500 people gathered for the first Pink Dot, while in 2013, two court cases were mounted to challenge the constitutionality of 377A.

Encouragingly, the government has shown some willingness to engage with the LGBT community, as public opinion is gradually shifting in our favor. However, these positive changes are happening only because the community has shown its true courage by stepping up.

And, for my part, there are times when I find I am caught up with my work and I lose sight of the fact that this is going to be a relay race, a shared and ongoing journey that no one can complete alone. Because the fact is that we are still walking through a long dark tunnel.

The good thing is that we can now at least see light at the end — we just need to keep walking.

Southern Africa

Anneke Meerkotter is litigation director at the Southern Africa Litigation Centre.

While it's hard to predict the future, the prospects of the eventual legal recognition of the rights of LGBT persons in southern Africa look better now than they did even just a year ago.

Anneke Meerkotter

In November 2014, the Botswana High Court held that the refusal to register a local LGBT organization amounted to a violation of the rights to equal protection of the law, freedom of expression and freedom of association. This decision was significant, as the court emphasized that the penal code offenses that criminalize consensual sexual activity do not criminalize homosexuality, nor do they criminalize advocacy for the reform of these laws.

Yes, this might seem an obscure distinction, but it’s important because it helps to carve out a space for organizing around the rights of LGBT persons in an environment where consensual same-sex acts still remain criminalized (as is the case in many countries).

A similar judgment was handed down by the Kenya High Court in May. Meanwhile, also last month, the Zambia High Court upheld the acquittal of activist Paul Kasonkomona, who was arrested in February 2013 after he spoke out on public television about the need to protect the rights of LGBT persons.

Kasonkomona's acquittal, after a lengthy court process, is noteworthy on a number of levels. Alleged arbitrary criminal offenses are frequently used against human rights defenders who speak out against human rights violations. With this in mind, it is important for courts to assert the right to freedom of expression, even where the ideas being expressed were controversial.

Indeed, in order to protect human rights in general and LGBT rights in particular, it is essential that we ensure that the rights to freedom of expression and association are protected in national constitutions and legislation, and not instead eroded through arbitrary, sometimes politically motivated prosecutions.

Peru

Gabriel de la Cruz Soler is the executive director of No Tengo Miedo, a Peruvian collective committed to promoting greater justice for LGBT people.

Almost three decades ago, a group of activists formed the first LGBT organization in Peru. Since then, lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans Peruvians began to fight against discrimination and sought the full recognition of our rights, despite the adverse social and political context that we faced. It is thanks to these individuals that there are now numerous organizations like ours working to create a more just and less violent country.

Gabriel de la Cruz Soler

Yet despite these advances, the state still does not recognize our families. It refuses to pass a gender identity law, or a law to protect LGBT people who are victims of violence. It also fails to include us in its national human rights plan.

It’s this reality that means groups like No Tengo Miedo (I Am Not Afraid) will continue to push and to join forces with activists, artists, educators and academics to expose our vulnerability as a community and to denounce the systematic and structural violence that our society and state too often perpetrate against our people.

Ultimately, we are doing this to make ourselves visible.

In recent days, we launched a campaign to collect stories from across Peru through our virtual platform www.notengomiedo.pe. As more and more people come out of the closet with us, we will be able to produce a document that can then be presented to the presidential candidates running in the 2016 elections. This will help candidates know and understand what is happening to us and why it is important to include us in their government’s plans.

Will our struggles bear fruit? We hope so, so that Peru can be a place where "defending life" does not mean devaluing life due to a person's sexual orientation or gender identity. We also hope to see a day when promoting the "interests of the child" will also include working against homophobic and transphobic bullying. And we want to see a time when promoting "equality and social inclusion" will mean including us in all public policies.

When we are visible, we are stronger.

The Philippines

Ging Cristobal is project coordinator for Asia at the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission.

When the Pew Research Center asked Filipinos if they agreed with the statement "Homosexuality should be accepted by society," almost three-quarters of respondents said yes. Yet, however promising this sounds, this rosy picture doesn't match the reality for far too many lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the Phillippines.

Ging Cristobal

The reality is that discrimination persists in both the workplace and the education system in the Philippines, while violence continues to haunt the lives of many gay men and transgender women. Meanwhile, stigmatization and bullying are still a curse for LGBT youth.

What has the official response been? Unfortunately, for the past 16 years, a national anti-discrimination law that would penalize and prevent discrimination against LGBT individuals and others has been stalled in the country’s legislature.

That said, there have been breakthroughs and pockets of progress around the country. For example, increasing numbers of local anti-discrimination ordinances have been enacted in cities across the Philippines, although these lack clear and specific details and processes to integrate them into the present legal, judiciary, and government system. As a result, these local efforts are left toothless.

As a result, the idea that there is "acceptance" in the Philippines creates a false sense that LGBT Filipinos are free and equal and that they live in dignity. Instead, the road to achieving the basic rights they were born with as human beings is still very much an uphill one.

Tunisia

"Tamarind" is an LGBT activist in Tunisia. He wrote under a pseudonym for his safety.

Back in 2011, Tunisians overthrew the oppressive Zine el Abidine Ben Ali regime, calling for justice, freedom, and dignity for all Tunisians. LGBTIQ people hoped for these things themselves, too. And yet four years later, gay intercourse is unlawful in Tunisia under Article 230 of the Tunisian penal code and is punishable by up to three years' imprisonment. Meanwhile, Tunisians and foreigners alike continue to suffer harassment, violence and even death over their sexual orientation or gender.

This is particularly disappointing because Tunisian activists had organized themselves into associations soon after the revolution in order to mobilize efforts at change and to challenge a penal code that is in outright conflict with the newly adopted constitution.

As in many other Arab, Muslim, and Mediterranean countries, LGBT individuals face numerous challenges in their fight for equality: religious conservatism, cultural resistance, intrusive laws and unsympathetic police forces. The situation has been all the more challenging because of the fleeting nature of post-revolution governments, the rise of political Islam and the emergence of extremism.

Still, a number of associations have continued to fight for equality, and activists are using social media to raise awareness, inform the public and mobilize individuals. Encouragingly, Tunisian media have started discussing LGBT rights, although this has itself spurred a wave of sometimes alarming reactions and opinions.

CNN

Updated June 22, 2015

Comments