"Undocuqueer" Transgender and Undocumented~~What Rights Do They Have?

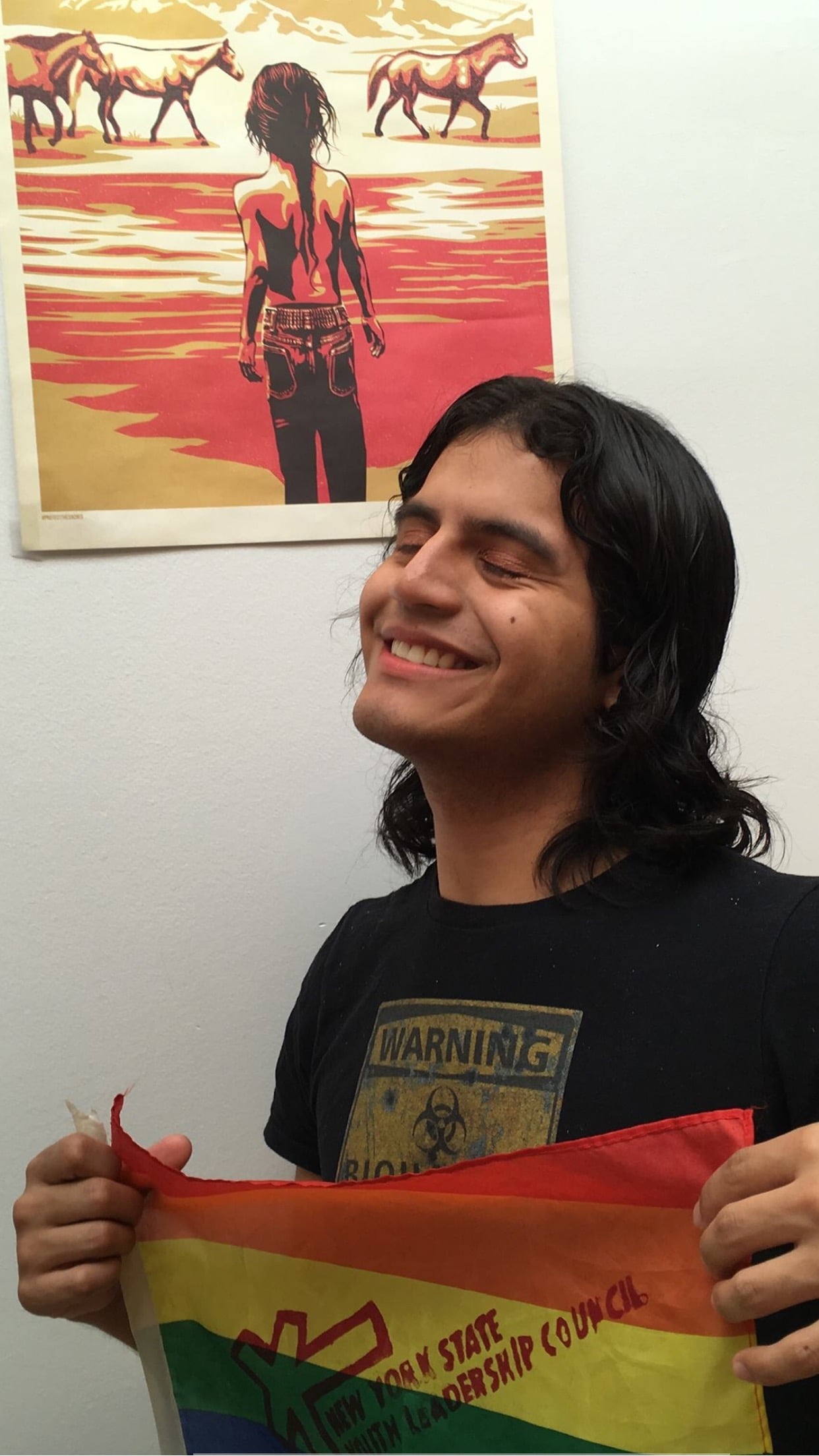

Ximena Ospina knows all too well what oppression looks and feels like. The 23-year-old transgender activist, who was born in Cali, Colombia, is a current DACA recipient. She lives in NYC, where she's been studying sociology and business at Columbia University since September 2016. It's a major change from where she was last year: homeless, alone, and with little opportunity in the workforce. Having come to the US from her home country as a young child, Ospina has had to fight for her place not only in this country but also within the Latinx community as a transgender, undocumented woman.

Ospina first came to the US in 1999 on a tourist visa with her sister and her father's cousin. The experience was traumatic for the then-5-year-old, whose parents had already immigrated and settled in New Jersey. The family overstayed their visas but struggled financially. A year after making a home in the US, Ospina's parents made a difficult decision: to send Ospina and her sister back to Colombia for a few months while they got their finances in order. They were later able to afford to fly their children back to the States on a tourist visa, which they overstayed. That time around, the US became Ospina's permanent home.

In 2018, Ospina is helping to unite undocumented queer individuals like herself who have trouble finding their tribe. She's a scholar under Point Foundation, which helps rising lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer students achieve their full academic and leadership potential. She's also a regular Section Leader in New York's Pride March and a translator for the New York Immigration Coalition. Ospina, who also goes by "Undocuqueer" on social media, spoke to POPSUGAR about her journey as a transgender woman and undocumented Latinx in a country where her rights are constantly targeted — and her strength and endurance underestimated.

POPSUGAR: What were the first years like, living as a child in a new country that you're not from?

Ximena Ospina: It wasn't too difficult because it was the best of an immigration POC enclave, I would say. Most people were either immigrants themselves or children of immigrants. Adjusting wasn't too hard because I was surrounded by Latinxs and people of color. I didn't feel necessarily excluded from the mainstream, only in that I noticed I didn't look like anyone on TV or movies. But we also just watched so much Latinx television that it wasn't even that big of a deal. If anything, I guess my biggest struggle growing up was just my femme-ness and my queerness. Most of the violence I received was about my queerness and not the fact that I wasn't a white American.

PS: When did you come into your identity not just as a Latinx but as a transperson?

XO: I didn't arrive to a conclusion or understand myself as trans until I turned 21. I came out as bisexual in 2010 but didn't come out to my friends as trans until 2015.

PS: Did you always know growing up that you were undocumented?

XO: I knew just because it would always come up in conversation. I didn't feel shame about it. I grew up being fully aware that I was going to be forced into undocumented misery, but that didn't affect me a lot growing up.

PS: Did you experience the effects of being undocumented when you first signed up for DACA or when you were trying to pay for school?

XO: I started to feel the main effect of it probably during driver's ed, which was in high school. It was mandatory, so I knew that even if I did well in the class and if I passed the driving test, there was no point because I still couldn't get a license. But again, there were so many undocumented people in school that it was very normal. It was just stressful. DACA came out after I graduated, so that entire time, I couldn't make any money, and my parents were not interested in giving me allowances or anything. I had to sell garbage bags to groups of teachers and random stuff to members of my school just to pay for prom and the senior retreat.

PS: When did you first sign up for DACA?

XO: The day after I graduated high school. But I didn't get my DACA [status] until February 2013. I was happy not to be working under the table [anymore] because before I got my DACA, I was working at a warehouse and working in landscaping.

PS: Were you going to school while working?

XO: No, I wasn't. I didn't go to college right after high school. I was only going to school part-time, paying for two classes at a time in cash because the scholarships weren't [as] plentiful as they are now.

PS: Do you remember specifically what it felt like signing up for DACA? Were you nervous about trusting all your information to the government?

XO: I wasn't scared. I really just had faith in the government and everything that Democrats were saying and Obama was saying. I was just excited to be able to work and have a life — and just being able to get my own car and drive, because my relationship with my parents wasn't good, and I depended on my dad a lot for rides.

PS: What was the process like?

XO: It was a little nerve-racking because I did it all by myself. I didn't want to spend money on lawyers, and lawyers were really predatorial at that time. I was mostly frustrated to have to drop all the money [for the DACA application]. (Editor's note: an initial DACA application costs roughly $465.) That was already very painful to come by, doing all these manual-labor jobs.

PS: What would you say are some misconceptions about DACA recipients?

XO: A misconception is we deserve more sympathy than other immigrants. I feel like we're just lucky to have [immigrated] at a certain age. (Editor's note: DACA recipients must have entered the country before their 16th birthday and been under the age of 31 in June 2012 to qualify.)

"I used to think of myself as a Latinx person who happened to be undocumented but was actually part of the LGBTQ community. As I began my activism, I began to think of myself as belonging to both communities."

PS: Was this during your coming out as a transperson? Did you have to change your name in that paperwork?

XO: I actually decided that all of this — legally changing [my] birth name and gender — is going to have to happen after I've gained status, which is a really depressing thing and certainly causes me daily anxiety and depression. It's hard to live with, but I know I probably won't legally be able to change my name for a while.

PS: How would you describe your activism?

XO: I think my activism is more focused on intercommunity building more than awareness raising. My activism used to be more about awareness raising at the beginning until I realized, again, we're preaching to a choir, really. Because none of this is about awareness or understanding systems. It's really just like a very intentional forced oppression of people.

PS: Would you say there were parallels between finding your queer community and also finding your undocumented community?

XO: I used to think of myself as a Latinx person who happened to be undocumented but was actually part of the LGBTQ community. As I began my activism, I began to think of myself as belonging to both communities. As times progressed, my work got more comprehensive. I realized that it was a waste of my time and energy to fight for both communities as a whole, and [instead I fight] for the people that go through my experiences.

PS: Would you say that everything you're describing to me right now is what inspired your activism?

XO: I think my activism comes from my loneliness . . . from the fact that my sister left the house when I was 13 and she's never come back, really. She visits, but she wasn't allowed back into the country [from Canada] for 10 years, so I grew up without her. That upbringing created this sense of loneliness in me, and so as I became an adult and had more control of my life, I sought out these communities because I realized, yes, there is such a thing as oppression and hatred.

PS: You have experienced homelessness. One in five transpeople has experienced discrimination when looking for a home, and more than one in 10 has been evicted from their home. What do you think this country can do to lower these numbers?

XO: People who are looking for roommates have to cut the whole gender bullsh*t because a lot of my homelessness was exacerbated by the fact that people were specifically looking for cis [roommates]. What they really should do is look for roommates who won't kill them and who need the housing they're offering.

PS: Have you met a lot of LGBTQ+ people through DACA?

XO: I feel like DACA was rather inconsequential to my life in terms of how I socialize, really, or who I socialize with, until I started activism. I felt it was really important to have undocumented folks around me. It's definitely been a lot of work because undocumented queer folks . . . it's so hard for us to have spaces to come together. I'm just glad that my work basically has been to put me in touch with people like me.

PS: Is there something from the undocumented queer experience that you would want people to know about?

XO: I want people to begin to realize that the curves of political agency, or at least navigating the political climate of these days, that [undocumented queer people] are actually masters at it. I feel we hold the freaking keys to survival because we already know what it's like to fight for LGBTQ rights. And we already know how to live under that kind of pressure and that kind of hatred and that kind of demand to constantly validate yourself. I think what's more frustrating is that even the cisgender heterosexuals of the immigrant rights movement totally disregard just how much experience we have with oppression.

PS: Can you tell me how you felt the moment Trump set his sights on DACA?

XO: I wasn't surprised. I was just like, "OK, how am I going to survive now? And how am I going to make sure I show up for people who are going to be suffering?" The day he rescinded DACA, I was actually outside Trump Tower during the press statement. I was by Trump Tower protesting, yelling, the whole shebang. Because at that point I knew there was nothing else I could do except yell and let out my anger.

PS: Do you feel the pressure to have a "Plan B" if they take away DACA?

XO: I have "Plan B through Z." I don't think any undocumented person at this point doesn't have a "Plan B" . . . it's always been trying to find ways that I can apply for some sort of protection because I'm trans. My deportation is a little like a death sentence because transwomen of color in Latin America don't live past their mid-30s. They're murdered or they kill themselves from abuse. (Editor's note: according to a report by Transgender Europe, 82 percent of reported trans murders between October 2016 and September 2017 were in Central and South America.)

I'm lucky enough that I have gathered resources for myself that might possibly ensure that I can live a freelance livelihood doing what I like, but I know that's a very privileged position, and I know that a lot of undocumented queers don't have the opportunity or the option to rely on their status to survive.

Comments