Ukraine Pressures NATO on Becoming Part of The Alliance-NATO Seems Positive

|

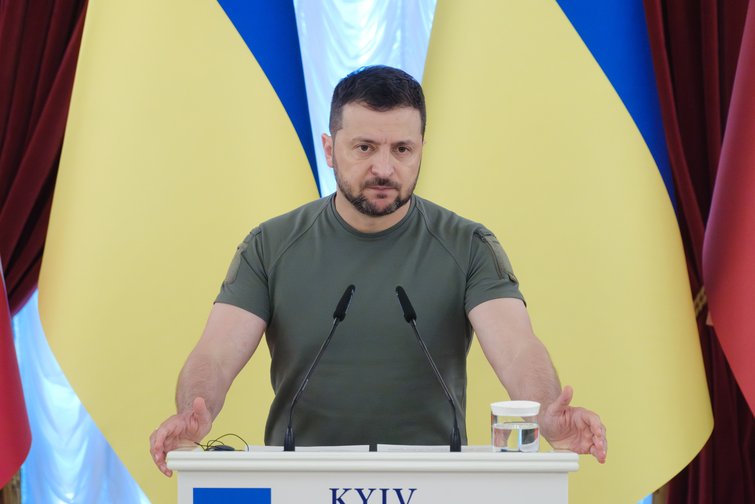

| Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelenskyi has said his presence at the NATO summit depends on whether Ukraine receives a clear timeline for joining | Vitalii Nosach/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images |

e highly-anticipated NATO summit in Vilnius next week is seen by Ukrainian officials as pivotal for the future of their country as they push for security guarantees and a path to membership.

Speaking on Wednesday, President Volodymyr Zelenskyi told Ukrainians the summit in the Lithuanian capital would be “a key moment for our common security in Europe”, adding: “Everything depends on our partners.”

The summit comes with Ukraine in the midst of a closely-watched counteroffensive to liberate its southeastern territories and Crimea from Russian occupation.

With expectations high from both the public and officials about the success of the counteroffensive – which is backed by Ukraine’s Western allies – there is an impression that the government has limited time to make important decisions on long-term security and cooperation with the West. Membership

Ukraine wants its application to join NATO, submitted in September last year, to be accepted the day after it wins the resistance against Russian aggression.

Zelenskyi has more than once stated his presence at the summit depends on whether Ukraine receives a clear timeline for joining NATO. This has forced Western capitals into publicly discussing their views on accepting Ukraine’s fast-tracked membership – not at some unspecified point in the future, but as a real possibility.

Baltic countries, central Europe, and notably Great Britain and Italy, say they are ready to see Ukraine among the ranks of NATO members. But the stance of the US – labelled by Zelenskyi as a “decision maker” – is that “Ukraine would have to make reforms to meet the same standards as any NATO country before they join”.

Serhiy Kudelia, associate professor of political science at Baylor University, believes Ukrainian officials’ firm demands of membership status is a negotiating tactic designed to draw important decisions on arms supply and media attention.

By pushing for a formal invitation to the alliance, Ukraine might hope to reach a middle ground with its partners at NATO and receive some of the more serious arms aid that has been blocked recently, Kudelia says.

So even if Ukraine doesn’t get a clear message on membership, Kudelia believes Zelenskyi should attend the summit, saying Ukraine’s participation itself would be a “historic event”.

“To avoid participation, no matter what the conclusion will be for Ukraine, I think it will be a mistake. And I think [Zelenskyi’s] appearance there on par with other NATO leaders would by itself be a very significant win for Ukraine diplomatically,” Kudelia notes.

“If there is no breakthrough there, no major progress in terms of membership, so be it,” thinks Volodymyr Dubovyk, associate professor at Odesa Mechnikov National University. “We should continue to talk to our allies and friends and partners in NATO explaining, again, why Ukraine needs NATO, why NATO maybe needs Ukraine. We should continue this conversation, so the Vilnius summit is not the end of it.”

Security guarantees

NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberg has already said the alliance will “sustain and step up support for Ukraine” at the Vilnius meeting.

And speaking on 4 July, Lithuanian president Gitanas Nausėda said a number of countries are preparing additional military support for Ukraine to announce at the NATO summit.

Yet the nature of the security guarantees for Ukraine remains unclear.

“We have not heard any specific commitments yet,” Kudelia says. “And that's another issue that may be decided at the summit: whether instead of NATO as an alliance providing security guarantees to Ukraine, we will see a temporary solution in the form of a multilateral security arrangement that would resemble something like what South Korea or Taiwan receive from the United States and other Western countries.”

None of the documents or frameworks that were created over the last year, like the Kyiv Security Compact proposal, the NATO-Ukraine Commission or the discussed Israeli security-type commitments, include any real details on what Ukraine’s security commitments might look like.

The Kyiv Security Compact is a document developed by a group of international experts led by head of the president's office Andriy Yermak and former NATO secretary general Anders Fogh Rasmussen. But it contains only broad recommendations for a security agreement that would introduce guarantees to Ukraine after the war to prevent a repeat of Russia’s aggression.

“The Yermak-Rasmussen [compact] is still on the table,” says Kudelia, noting it could “become more formalized” in the future, including at the Vilnius summit. But that would require specific provisions on arms supplies, economic help for reconstruction, intelligence sharing, and military training – even to the point of deploying Western troops, he said.

NATO’s deputy secretary general Mircea Geoană, in an interview with Digi24, said while Ukraine waits for progress on its membership, the alliance is working on an assistance package and security guarantees.

For Zelenskyi, though, these security guarantees are not an acceptable replacement of NATO membership.

“Ukraine doesn't want any hollow, meaningless guarantees or assurances. It needs some very concrete, very committing, very binding guarantees,” says Dubovyk. For the most part, he says, Ukraine needs to “receive immediate assistance, including actual boots on the ground”.

“What Ukraine needs, our allies and our partners are not ready to provide us with. So on guarantees, we've kind of hit a dead end in a way,” underlines Dubovyk.

Estonian prime minister Kaja Kallas said this week that bilateral agreements on security guarantees "blur" the debate about Ukraine's NATO membership.

“The only security guarantee that really works and is much cheaper than anything else is NATO membership,” Kallas told the Financial Times.

Zelenskyi and NATO members understand that Ukraine joining NATO will not happen until Ukraine ends Russia’s war. Thus, Kudelia believes that getting a formalized bilateral or multilateral framework in the near future “certainly would be a great alternative or very important step forward as far as improving or strengthening Ukrainian security”.

“I think if that type of agreement based on the Yermak-Rasmussen document is formalized, this is the best that Ukraine can hope for prior to the end of the war,” Kudelia said.

Comments