American Gods Gives You Food For Thought About Religion

The first season of American Gods ends with an image that compacts the many themes of the series into one odd moment. It's an aerial shot, slowly revealing a line of cars, buggies, and other vehicles crowding the tiny road to a neglected Wisconsin tourist trap called The House on the Rock. Without giving you any spoilers, I can say that this scene captures American Gods' perspective on religious faith in America.

And now, with a generous dose of spoilers, I will tell you what I mean by that.

Though we were left on a cliffhanger, the season's final episode, "Come to Jesus," did resolve one major plot arc. We now know why gods still have power in what Media calls "an atheist world." She's not technically correct about that—surveys show that 89 percent of Americans believe in God(s). But this series, based on Neil Gaiman's 2001 novel, has managed to create a spellbinding story about how true belief rests on healthy skepticism.

From old gods to new

In this series, skepticism basically means understanding how the god sausage is made. That's why it's so satisfying when Mr. Nancy tells the complete tale of Bilquis in the season finale. Though we've seen pieces of many gods' biographies, we finally see a god's life cycle from birth to death to rebirth. It's the ultimate demystification of a mystical being.

Bilquis is known by many names: Queen of Sheba, Bar'an, moon goddess, etc. We meet her earliest worshippers at the Temple of Bar'an (near Ma'rib in modern-day Yemen) in 864 BCE, during what looks like a lunar eclipse. The ancient queen/goddess absorbs dozens of people in a ritual orgy version of what we saw in earlier episodes, where she pulls her sexual partners into the cosmos through her vagina.

But over time, politics and culture change the way she's worshiped. She's a sexually liberated disco queen in Tehran in the 1970s until forces from the Iranian Revolution raid a club where she's seducing a woman. That woman is Bilquis' bridge to America, and when the woman dies of AIDS in the 1980s, Bilquis is bereft. Her once-glorious visage appears only in menus for Middle Eastern restaurants, and she hears about her ancient temple in television reports of fighting in Yemen that has damaged her altar. By 2013, she's living on the street, nearly dead.

That's when the change happens. Technical Boy facilitates the rebirth of Bilquis by offering her a mobile phone, installed with a Tinder-like app called "Sheba." Here we're seeing a deal similar to what Vulcan took, and what Mr. World and Media offered Wednesday earlier in the season. Her ancient worshipers will return, delivered via a modern device. She's no longer worshiped for herself, but as one part of a much bigger system that delivers what Wednesday sneeringly calls "existential crisis aversion." Still, she gets her sacrifices. As Mr. Nancy points out, she survives.

At first, it appears that Bilquis lives only at the pleasure of Technical Boy, Media, and the other new gods. That's what seems to be the case with Vulcan, too. But the real message of this series is quite the opposite.

Religious Darwinism

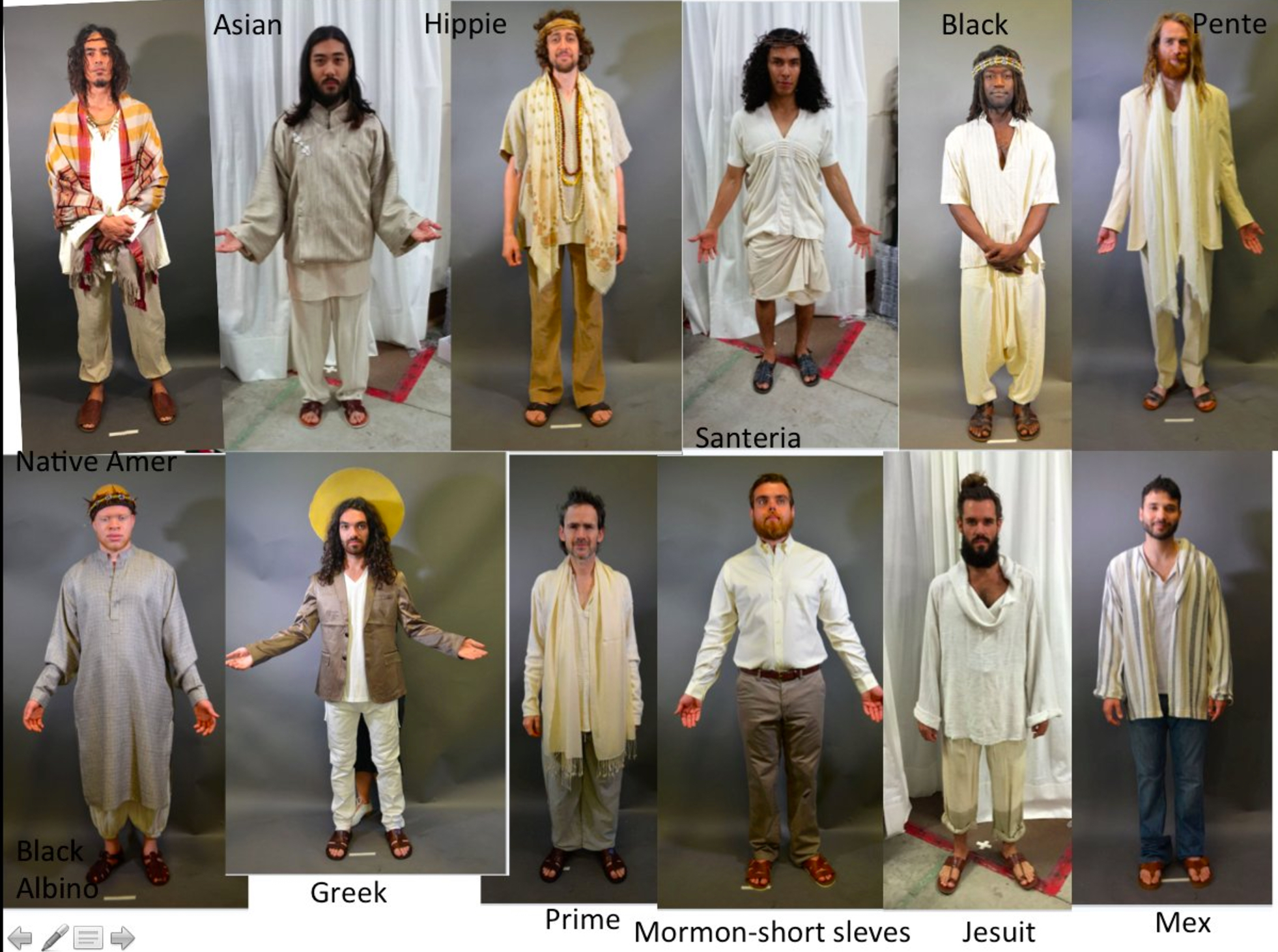

When we meet all the Jesuses (Jesusi?) at Ostera's Easter celebration, we learn the secret that the new gods are trying to hide: no god, no matter how popular, can ever monopolize human faith.

What's brilliant about the Easter scene, with its multi-ethnic, multi-sect Jesus meetup, is that it manages to respect Christianity while at the same time suggesting that it isn't quite the monolithic faith that you might expect from the world's most popular religion. When we see all those Jesuses, it becomes clear that Christianity is many things to many people. There is no single Christian faith, and therefore the idea of "one God" is impossible. I called this a respectful (though playful) representation because the holiness of Jesus is never called into question. We are simply reminded that America is a land of many gods, and several dozen of them happen to be different flavors of Jesus.

More to the point, Jesus himself depends upon Ostera to provide context and significance for his holiest day. Though Media insists that Easter is only relevant because it's a Christian holiday, we already know that all the trappings of Easter come from the worship of the pagan goddess of the harvest. The egg hunt, the candies, the imagery of animals and flowers—all these things belong to Ostera. It is a perfect hybrid of two kinds of worship, one old and one relatively new.

To return to my earlier comments about Bilquis, this is clearly the case with many rituals of worship in American Gods. Bilquis gains her power from ancient beliefs in what Mr. Nancy calls "the power of rebirth and creation," combined with the desire for connection and sex that fuel our worship of Technical Boy's Internet. Vulcan combines the Bronze Age worship of forge and sword with modern fealty to guns and state power. Ostera's power encompasses Neolithic prayers for a good harvest and modern Christian ritual.

Media calls it "religious Darwinism," where old gods adapt to the new world. And as that world keeps changing, Media warns, one-day humans could "all decide that God doesn't exist." That's why the old gods need "the platform and delivery mechanism" of television, movies, the Internet, and whatever it is that Mr. World embodies.

Media calls it "religious Darwinism," where old gods adapt to the new world. And as that world keeps changing, Media warns, one-day humans could "all decide that God doesn't exist." That's why the old gods need "the platform and delivery mechanism" of television, movies, the Internet, and whatever it is that Mr. World embodies.

And yet, as for Wednesday retorts, humans still desperately need to be inspired by gods. Partly that's because they "wonder why things happen," and partly it's because they want someone to blame when things go wrong. But more than that, it's because gods offer humans a simple, appealing bargain. As Wednesday puts it, "You want to know how to make good things happen? You are good to your gods." None of the new gods can offer this bargain because they are just a delivery mechanism, an amplifier.

The new gods depend on the old gods for what Technical Boy would probably call "content." And that, ultimately, is the message of the first season of American Gods. Beneath the glamor, guns, and vape smoke, there's a raw need for the primal bargain that ancient humans struck with the very first gods. We offer them a good sacrifice, and they make good things happen.

(De)constructing faith

In America, where many cultures flow together, faith is as diverse and hybridized as humanity itself. Though American Gods have sometimes stumbled in its effort to represent a full range of religions, cults, and superstitions—and appears to have entirely forgotten that Native Americans exist—it has still crammed an astonishing diversity into eight episodes. What has emerged is an arc that tracks how a nation of immigrants wove a mystical firmament of immigrant gods.

Immigration is, in fact, fuel for faith. America's new gods depend on imported forms of awe, like Bilquis' cosmic eroticism, to lure in new believers. Plus, new-ish gods like Jesus gain power entirely because they are designed for export, nationally and culturally. While Odin is one god with many names, Jesus is many gods with one. He represents hundreds of localized instances of faith that can easily be snuffed out. Indeed, one episode begins with the death of a Mexican Jesus, who is shot down when Vulcan worshipers murder a group of illegal immigrants at the US border.

American Gods revel in the beauty and power of faith, but this show isn't afraid to admit that gods are created by humans. It's a difficult line to walk, and we've watched Shadow try to walk it throughout the season. He begins as someone with no belief in anything other than Laura, the (secular) love of his life. But by the final episode, after Odin reveals himself, Shadow professes belief in "everything." This is what American Gods asks of its audience, too. We must believe everything and nothing. We must assume that gods are real, but also know that they are our creations.

That's why the series' final scenes are such incredibly complicated moments. We watch as Ostera, a queen who has deep roots in ancient and modern faiths, reveals her true power. "I feel misrepresented by the media," she tells Media. And then, a few beats later, she uses her power to steal spring from the world in a kind of magical eco apocalypse. This is a feat far beyond anything we've seen even from Odin, and it comes with a demand for worship.

"Tell the believers and non-believers we’ve taken the spring," Wednesday announces to Media. "They can have it back when they pray for it." As those words sink in, our perspective pulls back to reveal that Laura has arrived. Now the lure of Earthly love is in the mix, tugging at Shadow's loyalties. And finally, we pull all the way back to see the gods are arriving for some kind of showdown at House on the Rock.

House on the Rock is the perfect location for a meeting of the gods as we have come to know them. It combines an ancient need for sacred natural places with a modern-day hunger for cheesy distractions. The fact that it can be both of these things reveals why a war between old gods and the new gods would be catastrophic. These gods don't just need each other; they are each other. They cannot be unbound.

The many unfinished plot threads will continue to unwind next season, but this season ended with a satisfying reveal. We discovered that gods are a cultural construct, but nevertheless, they still have the power to destroy the world. In American Gods, there is no contradiction between knowing something is imaginary and having faith in it.

Listing image by Starz

Comments