Clinton’s Secret for Winning Fl: Arriving Voters from PR

Last Wednesday morning contained an unusual landmark in the endgame of the 2016 election season: the first time in months that Central Floridians could confidently buy a plantain without being hassled about their level of civic engagement.

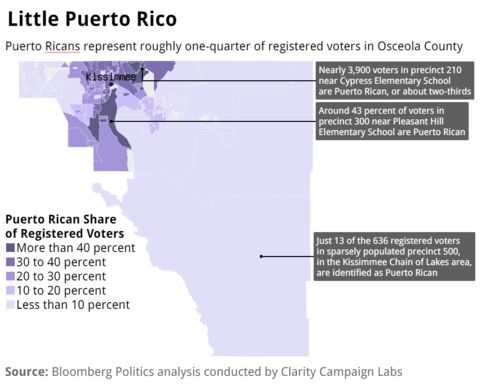

Throughout the year, their region has been overrun with clipboard-grasping canvassers listening for the distinctively accented Spanish of native Puerto Ricans. While in most states registration drives focus on college campuses and African-American neighborhoods—the standard marketplaces where canvassers find non-registrants who skew Democratic—Florida has presented a distinct demographic opportunity. The center of the state, across several counties sprawling outward from Orlando, has been a destination for one of the most significant domestic diasporas in recent American history. The debt crisis that has been roiling Puerto Rico for the last two years has forced residents to flee the island in droves, with many settling in Florida’s Orange and Osceola counties.

“From senior citizens to 22-year-old college students, anybody who’s anybody is moving here from Puerto Rico,” Clyde Fasick, a student from the Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico working on Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton’s campaign in Osceola.

“From senior citizens to 22-year-old college students, anybody who’s anybody is moving here from Puerto Rico.” Clyde Fasick, Hillary Clinton campaign organizer

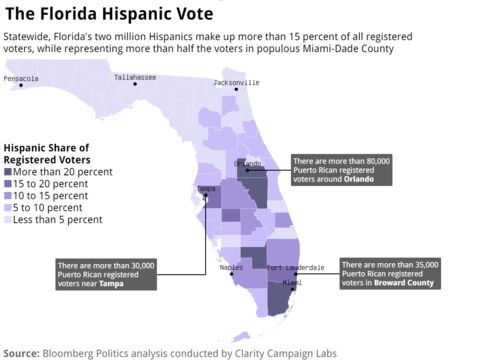

Four years ago, President Barack Obama won 60 percent of Florida’s overall Hispanic vote, compared to Republican Mitt Romney’s 39 percent. This year, some national and Florida polls have pegged GOP nominee Donald Trump’s support among Latinos below 20 percent—a difference that could place this ultimate swing state securely into Clinton’s column, if her campaign can reach its turnout goals. Trump and Clinton each scheduled multiple days in Florida this week, no doubt aiming to reach the 2 million Hispanic voters who now make up roughly 16 percent of registered voters in the state. And in contrast with South Florida’s Cuban-Americans, a swing constituency both sides have long struggled over, Puerto Ricans in the state look this year to be an overwhelmingly Democratic bloc, requiring not ideological persuasion, but the arduous labor of registration and mobilization.

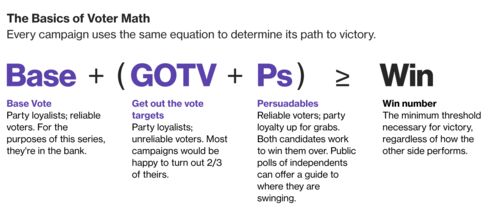

In a report released by WikiLeaks after Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta’s e-mail account was hacked, the campaign’s analytics team determined that nearly one-quarter of the work required to win Florida was registering new voters. In comparison, that number was less than 10 percent in Wisconsin, and nearly 60 percent in North Carolina. (The Clinton campaign has declined to verify the authenticity of the hacked e-mails.) Some of that work has been taken on directly by Clinton’s campaign, under the auspices of the consolidated field effort it runs with the Florida Democratic Party, but the campaign also benefits from the attention of non-profit groups that coordinate work among themselves. (As non-profits, they are forbidden from sharing their plans with Clinton’s campaign, though signaling sometimes takes place through the media.)

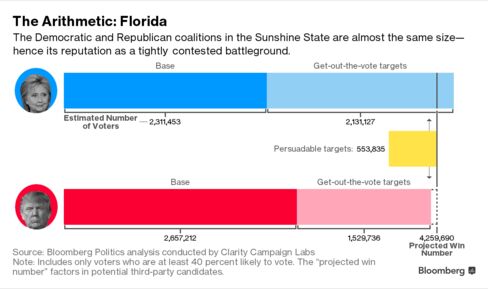

Despite Florida’s hallowed swing-state reputation, its well of 554,000 persuadable voters is shallow—a relatively small share of the electorate. Obama was able to keep this state blue for the past eight years in large part because Democrats have a sizable advantage when it comes to the number of supporters they can attempt to mobilize, with more than 60,000 targets than what's available to Republicans. (Four years ago, after more than 8 million ballots cast in the state, Obama won by about 73,000 votes.)

Trump may seek help from the 60 percent of persuadable voters who are over the age of 50—especially men. But this year, almost every other key demographic groups seems to be tilting in Clinton’s favor. There are nearly 30 percent more women in Florida who lean Democrat than Republican—a gap that is 10 points wider than the split among men. Clinton also has more than twice as many mobilization targets than Trump within the state’s swelling Hispanic communities.

She may find additional support among the state’s 415,000 Republican-leaning Latinos, many of whom appear to be standing behind incumbent Republican Senator Marco Rubio as he distances himself from Trump. If Clinton can turn out the entirety of her coalition and peel off 45 percent of Latinos who’ve leaned toward the GOP in the past, she could win the Sunshine State without the help of a single persuadable voter.

Ground Forces

Last Tuesday afternoon, three Clinton canvassers stood outside Kissimmee Meat & Produce, looking to slow those entering and exiting just long enough to ask whether they were registered. The independently owned supermarket sits in Osceola County’s 410th precinct, where, according to a Clarity Campaign Labs analysis, 42 percent of the 246 voters who have registered since the 2014 elections are likely to be Puerto Rican. Not all are recent transplants from the island: some were raised in Florida and are just reaching voting age; others are retirees relocating from large Puerto Rican communities in New York, New Jersey, and Illinois.

Not long ago, Democrats worried that the new arrivals would become a key swing bloc. These voters do not come with partisan loyalties—Puerto Rico’s two parties are not split on a left-right axis as much as by their support for statehood—so even people who are enthusiastic about voting can become paralyzed when prompted to check a box attached to a party name. Clinton has been vocal about her support for Puerto Rico's right to vote on whether it should be a state—past polling suggests such a measure would pass comfortably—while Trump has signaled he is open to the possibility of statehood. “I realize some of them don’t recognize which candidate is Democratic and which is Republican,” says José Castellanos, who supervises a team of four canvassers for Mi Familia Vota. “As soon as I say a certain name, they react.”

Earlier this year, Democrats were aggressively testing messages they thought could sway new transplants to line up with Democrats, mostly by contrasting party leaders’ backing for a federal bailout of the island with Republican opposition. The communications department of Clinton’s Florida campaign has treated San Juan as a local media market, working as assiduously to place stories in El Nuevo Dia de Puerto Rico as in the Sun-Sentinel. New transplants are as likely to read news from their former home as from sources in the Orlando media market.

To help target narrowly tailored messages to these voters via digital ads and direct mail, Civis Analytics, a firm working for the pro-Clinton super-PAC Priorities USA, built a statistical model to predict the ethnicity of every Hispanic voter. Florida is among the states where citizens have been historically required to identify their race or ethnicity when registering to vote, but forms don’t distinguish Puerto Ricans from, say, Colombians or Venezuelans. “It’s very important to differentiate Cubans from non-Cubans in Florida,” says Matt Lackey, vice president for research and development. The Civis analysis found Colon and Nieves were the last names that most over-index among Puerto Rican voters, compared to Morejon and Llanes among their Cuban peers.

It turned out that it did not take much persuasion to move the new Puerto Ricans into Clinton’s column. Latino Decisions, a polling firm that supplies her campaign with research on Hispanic public opinion, found Clinton winning 74 percent of the vote to Trump’s 17 percent, with an even larger margin among the subset of those born on the island. The island-born viewed Clinton more favorably, and Trump more unfavorably, than their mainland-born peers. And within both groups, only 11 percent of voters said the debt crisis was the most important issue to them, behind even “immigration or deportations”—even though as citizens those issues are unlikely to affect Puerto Rican families directly. In Florida’s Senate race, Puerto Ricans were split between the Cuban-American Rubio and his challenger, Patrick Murphy, with the island-born leaning toward the Democrat, and mainland-born slightly preferring the Republican.

So Democratic campaigners shifted Puerto Ricans from targets for persuasion to pure mobilization opportunities. They would not need to be convinced to vote for Clinton, sure, but they did need to be registered and then mobilized to participate, in a place with a very different electoral culture.

Unlike foreign immigrants, as U.S. citizens, Puerto Ricans are all immediately eligible to vote, and many are more habituated to voting than many Americans. Puerto Rico has some of the world’s highest voter-turnout rates, which observers credit both to the fact that Election Day is an official holiday and to the block-party atmosphere that inspires. For years, Puerto Ricans voted at a higher rate than Finns; the only countries in the hemisphere with higher participation rates made voting compulsory. Even though turnout for the island’s quadrennial elections has fallen in recent years, it is still 10 points higher than for presidential contests on the mainland.

That hasn’t always translated into similar participation for Puerto Ricans on the mainland, where their turnout rates lag behind the population as a whole. (Civis Analytics projects turnout among Florida Puerto Ricans this year to be 10 points lower than among Cubans.) “When people come to vote here, it’s heavy,” says Fasick. “It’s a more festive feeling back home.” Organizers have been working to recreate some of that spirit in Central Florida, snaking the boisterous automotive caravans known as caravanas through Orlando and Kissimmee. Clinton’s campaign has started blasting music at local phone banks as volunteers make calls.

Story has been updated to more precisely characterize Hillary Clinton's position on Puerto Rican statehood.

This is the seventh in a series of eight Battlegrounds 2016 stories on the unique arithmetic that governs presidential elections in battleground states. Read more about how the battleground game is played.

—With assistance from Andre Tartar

Comments