Gay Men Can Now Donate Bone Marrow(life saving) in the US

This posting appeared a couple of hours ago on the nbcnews.com by . Iam posting it here just as it appeared on NBC”s post. All credit is given to NBC. Due to time limitations and importance of the story this blog wanted it posted as soon as possible and after editing to fit in our page it was posted here.

Cara Pagels was teaching in South Korea when she found out she had aplastic anemia. Like many people who are diagnosed with bone marrow disorders, she didn't know what the disease was.

"The first time I heard about it, I assumed it was something I could fix by taking iron pills," Pagels told NBC Out.

The reality is that aplastic anemia, a rare condition that affects just two in a million people, devastates the body's ability to make new blood cells. Patients commonly suffer from organ failure, spontaneous bleeding and even brain hemorrhage as a result. The causes of the disease, which are thought to be exposure to toxins and pesticides, are unknown, but its impact can be fatal. Aplastic anemia can be treated with medications and transfusions. But for Pagels, without a bone marrow match, she could die.

In July 2016, the 26-year-old left her job and her school in South Korea, where she had spent three years teaching. She initially headed to the East Asian country after tutoring at a refugee center, and while there, she said she "absolutely fell in love with teaching."

Patients in need of a bone marrow donation often face extraordinary challenges to finding that perfect match. While there are eight different blood types, there are millions of varieties of tissue types. Some people will never find a donor, and for the 13.5 million people currently enrolled in the National Bone Marrow Registry, there's only a 1 in 430 chance volunteers will ever be called upon to donate tissue.

But for Pagels, the challenge is also personal.

Many of her friends are gay or bisexual and historically unable to donate to blood centers under Federal Drug Administration policy. The FDA placed a lifetime ban on men who have sex with men (MSMs) until December 2014, when the policy was lifted in favor of a 12-month deferral period. Accustomed to being turned away from blood centers due to the fear they might transmit HIV, Pagels' gay and bisexual male friends were worried they wouldn't be able to help her out.

Christopher Rosner, 26, a longtime friend and former coworker of Pagels', attempted to donate blood in college, prior to the new policy being put into place. Rosner, who wasn't aware of the ban on MSM donations at the time, said he was "furious."

"It was the first time I had ever been discriminated against because of my sexual orientation," Rosner said, adding, "There's plenty of people who would be willing to help out, but we can't."

That groundbreaking policy change traces its beginnings all the way back to 2005, when Be the Match first received guidance from the FDA that populations considered at "high risk" for HIV transmission could donate bone marrow in instances of extreme urgency -- such as an instance where an individual who had previously been banned from the registry constituted the only match for a patient in need of a life-saving donation.

Enforcement of those guidelines, however, was slow to change. Gay and bisexual men continued to be turned away for bone marrow donation until last year, as Medium writer John Colucci found out when he attempted to sign up for the registry in February 2015. Be the Match told him in an email that the group was working to "amend our policy and be more inclusive of potential donors while continuing to ensure safe and effective marrow donations for patients in need."

Just 10 months later, the group stopped asking questions about donors' sexual orientation during the recruitment process. As Director of Community Engagement Mary Halet explained, this decision was made after years of consultation with guiding committees and infectious disease experts.

"What we learned over time is that as donors donated having those risk factors, we found consistently that their infectious diseases were negative," Halet said. "Patients were not placed at any additional profound risk. The risk of dying from leukemia or blood cancer is far greater than the potential risk of dying from infectious disease transmission."

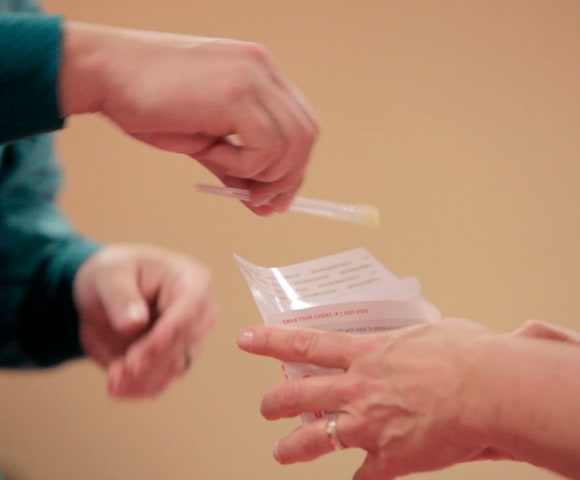

To sign up for the National Bone Marrow Registry, Be the Match representatives collect tissue from the inside of donors' cheeks with a Q-Tip. Each potential donor is then put through a rigorous screening process. If selected, volunteers are first tested to make sure their human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing matches the cotton swabs collected at registration. After that, tissue samples are put through two rounds of infectious disease testing, which scans for diseases ranging from HIV to Hepatitis B and the West Nile Virus.

During screening, donors are asked additional questions on the basis of individual risk. Italy and Spain have switched to a similar system for blood donations, which determines eligibility based on behavioral factors like intravenous drug use and unprotected sex, without an outbreak of infectious diseases in the blood supply.

"We've had no pushback," Halet said of the decision to allow MSM donations. "The response has been very favorable."

Jason Cianciotto, the Vice President of Policy, Advocacy and Communications at Harlem United, believes if allowing MSMs to donate tissue has had no negative impact on the bone marrow registry, the FDA should do the same for blood donation. The FDA, which regulates donation guidelines, sets its blood and tissue recommendations separately. It's time for the organization, he said, to update its policies to meet current scientific understanding on HIV.

"[The 12-month deferral period] is a scientifically unsound policy that particularly stigmatizes gay and bisexual male communities, as well as transgender women," he told NBC Out. "It carries forward the false notion that HIV is a gay disease. Gay and bisexual men who are HIV-negative and who practice safe sex, are married and in monogamous relationships, or on PrEP—and if they're taking it regularly, have little to no risk of contracting HIV—are effectively banned for life."

Some MSMs will remain celibate and be able to donate blood. A vast majority will not.

The original FDA policy dates back to 1983, when it was more difficult to test for HIV in the blood supply. Through rapid advancements in screening technology, the medical community has shortened that window, able to confirm presence of the virus in a blood sample as few as nine days. Today, the chances of contracting HIV through a blood transfusion are just 1 in 1.47 million, but the FDA, according to critics, remains stuck in the past. The government body has currently said it's reviewing its standards.

The impact of allowing gay and bisexual men to donate blood is impossible to underestimate. In 2014, a report from UCLA's The Williams Institute found that striking down the ban on MSM donations could increase the blood supply by 4 percent each year and could help save the lives of more than a million people.

While Be the Match said lifting the MSM tissue ban has generated excitement among LGBTQ donors, few are initially aware of the policy change. That knowledge gap continues to put at risk many of the individuals who are the least likely to have a match, most of whom are people of color. Thirty-four percent of African Americans in need of a bone marrow donation do not have a match, and the numbers are similar for Asian Americans (28 percent), Latinos (20 percent) and Native Americans (23 percent). In contrast, 97 percent of Caucasian patients have a match.

"Eighteen to 24-year-old male donors are our primary target," Melissa Betheil, an account executive with the New York Blood Center who works with Be the Match, told NBC Out. "Women get pregnant. When you're pregnant, you can't donate. When you're breastfeeding, you can't donate. We really want men to donate, yet excluded some of them for so long."

Pagels argues that it's important for blood and tissue centers to do further outreach to these communities and fight the stigma that keeps many from donating. It could save lives like hers.

"It's sad and depressing that people are rejected that opportunity to help fellow humans," Pagels said. "It really limits the chances we have for survival when so many people are being excluded from the registry."

Comments