Luke Evans, Actor "Was Bullied Before I knew What It Meant (gay)"

|

| Luke Evans photographed in Portland, Oregon earlier this month. Styling: Sara Paulson. Grooming: Terri Lodge Photograph: Mason Trinca/The Guardian |

In this exclusive extract from his new memoir, the star recalls his childhood as a ‘tormented tug of war’ between his faith and his sexuality

‘I thought I’d die at Armageddon’: read an interview with Luke Evans

Mam pushed open the front gate, which was hanging off by a hinge. The garden before us was a mess – an old sofa sprouting weeds and springs, a pile of half-burnt plastic toys – though we’d seen worse. The other day we’d had to edge around a large, angry-looking pony to get to the front door. It was 9am on Saturday, and, while most children my age were at home watching Going Live!, I was dressed in a suit and tie, knocking doors in a village up the valley with my parents and other Jehovah’s Witnesses to spread the word.

I had been doing this every week since I was born – an hour and a half on Saturdays, again on Sundays, and throughout the school holidays – but it never became any less of an ordeal. A few months earlier, we’d been in New Tredegar and a bunch of teenagers on bikes had followed us down the street, shouting, “Fuck off, you Jovey bastards!” Sometimes, when people started throwing things or set dogs on us, we would get in the car and leave, but this time we’d ignored the shouts and carried on.

Like me, Mam was smartly dressed. As a Jehovah’s Witness you always had to look respectable, because you were representing the religion. We always smelled nice; we smiled a lot and had neat hair. There was a lot of deprivation in the valleys and when people saw us at their front door, looking so clean and fresh and happy, it must have been a powerful draw. Join us, and you could be like this, too!

Mam was armed with a leather briefcase, inside of which were copies of the Jehovah’s Witness magazines, a Bible and a stack of report sheets, which would be filled out with notes such as: Number 48: do not call again orNumber 16: come back same time next week. She was a pioneer, which is what the religion calls those who knock doors regularly. Mam used to spend upwards of 60 hours a month doing the rounds of the villages of south Wales in a bid to save souls.

Mam knocked at the door; a few moments later, a woman opened it. “Yeah?” She was in her nightie, hair all over the place, a cigarette clamped between her lips. You could tell she was ready to say no even before she knew what we were there for – and, really, who could blame her?

|

“How are you this morning?” asked Mam. “Do you have a hope for the future?” The woman scowled. It was then that I noticed the boy. He was standing in the corridor behind his mum wearing Spider-Man pyjamas and, to my horror, I recognised him instantly. He was in my school, and he was looking at me with such disgust that I wanted to disappear inside my suit, bought oversized so it would last me a bit longer. I thought, this is not going to help me at school next week.

The door slammed in our faces before Mam had a chance to finish her spiel. She smiled down at me, undaunted as ever, and we made our way back down the path, my cheeks burning with shame. I hated knocking on doors. I hated forcing our ideas on people who had no interest, hated trudging around the rainy, grey streets when I could have been at home playing or watching TV. But I knew there was no point complaining. It was our moral obligation as Jehovah’s Witnesses to give as many people as possible the chance to come to “the truth” before Armageddon. We didn’t knock doors because we wanted to; we did it because we had to.

Though it’s been portrayed in movies as this monstrous, terrifying thing, the prospect of Armageddon didn’t scare me as a child. As far as I was concerned, it would just be God stepping in and stopping all the bad stuff that was going on in the world. Besides, I knew my parents and I were going to be saved, and would then live in paradise on Earth, free from violence, pain, war and crime. It was everyone else who was going to die in the storm of hail, earthquakes, floods, fire and sulphur.

My parents were brilliant at door-to-door work; they still are. They can talk to anyone. Years later, when I was an actor, I took them to the premiere of The Hobbit, and in the car home Mam told me she’d had a lovely chat with a man who had Welsh heritage. “He was so nice,” she said. “He told me this fascinating story about his childhood.” “What was his name?” “Oh, I can’t remember. He had a funny beard.” Well, that could have described hundreds of people in The Hobbit. “He was short,” Mam went on. “And had a funny accent. Australian, maybe … ?” I stared at her. “Peter Jackson?!” “That’s it! Who’s that then?” “He’s the director of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.” I couldn’t believe it. Peter Jackson is a very lovely, quiet and reserved man. I spent a year in his company, working with him and having dinners with his family, and barely knew anything about him, yet my parents had drawn out these deeply personal stories in a matter of moments in the chaos of a movie premiere party.

“Good morning, class. Please open your books and write today’s date at the top of the page.” I did as I was told. Monday, 15 April 1987. I frowned, staring at what I’d just written. The teacher had moved on, but I wasn’t listening. There was something about that date … “Oooh!” I was so excited that it came out as a shriek. “It’s my birthday today!” The classroom fell silent. At the back, somebody sniggered. I turned around to see a sea of faces staring at me, their expression one big: what the hell? You can understand why. This kid doesn’t know it’s his own birthday? What about when he woke up and opened his presents? Hasn’t he been planning a party? Didn’t anyone wish him happy birthday? But no, none of those things had happened. I’m not sure my parents would have even remembered it was my birthday, and, if they had, they had been told by the religion that celebrating was forbidden, so they’d have kept quiet about it.

To this day I’m still not sure when my parents’ birthdays are. One’s in August and the other November, I think. When I left home and celebrated my first birthday – my 18th – I tried to enjoy it, but I felt guilty, and that guilt stayed with me for a long time. The only events we were allowed to celebrate were wedding anniversaries and the memorial of Jesus’ death. This was the most sacred occasion of our year and was marked with an evening service at the Kingdom Hall on the night of the Last Supper.

During the memorial, unleavened bread and wine were passed around the congregation, but the only people allowed to taste them were the anointed. These were Witnesses who believed they are among the anointed, the 144,000 people mentioned in the Bible who have been chosen to go to heaven to rule alongside Jesus when they die. We knew a few of these and they were hugely respected and somewhat revered within the community. I have no idea how they knew they were anointed, but you couldn’t question it: if they told the elders they were one of the anointed, everyone had to believe them.

You can probably see a theme developing here: don’t question what you’re told. Do as the Bible says. Stick to the rules. And I guess this is fine, as long as it’s not doing anyone any harm, but for me it’s another matter entirely when it comes to the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ prohibition of blood transfusions. In the Bible, blood is portrayed as a sacred gift given to us by God. It’s not ours, so to pass it around is to break the sanctity of the gift. This was obviously written long before the invention of life-saving modern blood transfusions, but because it’s in the Bible the Witnesses are sticking to their guns. If you voluntarily accept a blood transfusion – even if it’s to save your life – you will be shunned by the community.

|

There was a young woman who died after she started haemorrhaging while giving birth and refused a transfusion. “It’s OK, I’ll be resurrected and will see you in paradise,” she promised her husband and newborn baby. It’s the most extraordinary belief. Unfortunately for my parents, I was first in line for accidents when I was growing up. One time I was messing around in the car park at the Kingdom Hall when I slipped and fell on my bottom, on to a shard of broken glass. I could feel I’d ripped my trousers, so I sheepishly went to tell Mam.

She was talking to someone in the foyer. “Mam?” “What is it, love?” “I’m sorry, Mam, I think I’ve torn my trousers.” I turned round to show her, and apparently the back of my trousers was completely soaked with blood, so much so that it was pooling on to the carpet. They rushed me to the little hospital in Aberbargoed, and while I was having stitches, my traumatised mother was passed out cold on the bed beside me. Thankfully, I always managed to hold on to just enough blood to avoid the issue of a transfusion, though I’ve been left with quite an impressive scar on my right bum cheek.

Like most Jehovah’s Witness families, we had a picture book at home called My Book of Bible Stories. I enjoyed reading about Adam and Eve, Noah’s ark, and Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt. There was one story that always unsettled me, though: the tale of Lot’s wife.

The story is intended to be about the perils of being materialistic. Don’t hang on to worldly things like Lot’s wife; the biggest television and nicest car isn’t going to help you when Armageddon comes. Yet as I got older, I discovered the reason the people of Sodom and Gomorrah were considered so abominable was because they were homosexuals.

The Bible doesn’t mess about when it comes to homosexuality: “detestable” is the word that’s used. According to the scriptures, “Men who lie with men” are up there with thieves, adulterers and murderers, and will die with the rest of Satan’s wicked at Armageddon. It gradually dawned on me that those poor people in my picture book were dying a horrible death simply because they were gay. God clearly considered that to be enough of a reason to burn them alive. And if you were a kid who was perhaps beginning to realise that you were different from other boys … Well, that picture was more than enough to make you keep quiet about it.

The first sense I had of being gay – or at least different – was at the age of eight, when our class got a substitute teacher. He played rugby for Llanelli and had a sharp haircut and a two-seater sports car. He was handsome and sharply dressed; all the girls fancied him, and all the boys wanted to be him. I remember staring at him, muscles busting out of his shirt, and thinking: wow. Even then, I knew I was looking at him in a different way from the other boys.

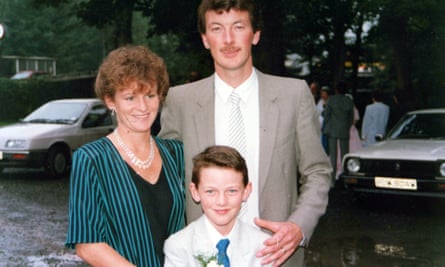

I was bullied for being gay before I even understood what it meant. The worst nickname was “Jovey Bender”, because it combined two aspects of my identity that could never be reconciled. It wasn’t possible to be a “Jovey” and a “Bender” because being gay was strictly forbidden by the religion. And so began a tormented tug of war in my head that would go on throughout all my years at school.

It’s a terribly dark place to be as a child, knowing you’re somehow “wrong”, but with no idea why that is or how you can fix it. I hated school. Children can be horribly intolerant; evil little bastards some of them. Anything slightly different about you and you’re a target – and I was different in almost every way possible. I remember a maths class where the only free seat was next to me and this boy wouldn’t sit down. To be treated like that as a child and made to feel there’s something intrinsically wrong with you … it’s so painful, and it stays with you. Even now, if you asked me what I looked like as a child, I would automatically reel off the things I was bullied about: big ears, skinny legs, hair that would never go spiky or lie in curtains like the other boys’. I felt inadequate physically, and that feeling grew with me into adulthood.

You might imagine that becoming famous would have helped, and I do have brief moments when I think: my God, people actually think I’m handsome?! But it’s all so separate from my daily reality, and that voice inside my head – the one telling me I should look younger, have better muscle formation or smoother skin – often drowns out any compliments I might be lucky enough to receive. Thankfully, I’m in a place now where I can get these negative feelings under control and appreciate myself.

As a young person you would usually have someone older who you could ask for advice, but I didn’t have anyone. If my mother had realised how prolific the bullying was, I know she would have stepped in, but I couldn’t tell my parents because I was too ashamed of the names I was being called.

So I stayed quiet, kept my head down, stuck with the other Witness kids and threw myself into my studies. Maybe it was because I had a lot of love at home, but even in junior school I knew it wasn’t me that was the problem, it was the bullies. Throughout my childhood, whenever bad stuff happened, there was a refrain going through my head: this is only temporary. Even at a young age I had this clear-eyed view. Once school was over, I knew my life would begin.

Comments