The FBI Infiltrated Gay Orgs During the Purple Scare of 1961

|

| You heard about the red scare of the fifties in which there was a communist undeer almost every bed but How About the purple scare? FBI went for the gays and infiltrated orgs.You don't have to be gay to laugh at that and you don't have to be gay to know that many times in our history the government was not, is not, our friend. |

By Eric Cervini

A story of queer liberation is concealed in a dystopian-looking crypt in Washington, D.C.

You can’t find it under the gilded ceiling and marble columns of the Library of Congress’s Jefferson Building. Instead, you have to enter the mammoth, rectangular Madison Building next door. The harsh lights and linoleum floors make it feel morguelike. In its windowless manuscripts room, uniformed archivists slowly wheel out boxes of documents from the depths of the building.

Only in this austere setting can you begin to understand the sheer magnitude of the modern fight for LGBTQ rights in America, which resulted from the Lavender Scare, the government’s systematic persecution of “sexually deviant” federal employees in the 1950s and 1960s. Thousands of American citizens lost their jobs because the government learned they were “perverts,” morally inferior, and therefore susceptible to blackmail by Communists. But a decade before the June 1969 uprising against police harassment led by trans and gender nonconforming bar patrons that became known as the Stonewall Riots, one disgraced federal employee fought back.

Frank Kameny, an under-recognized grandfather of the gay rights movement, was a victim of the Lavender Scare. A Harvard-educated astronomer, he had always dreamed of going to space, but after the government learned of his sexual orientation, he was barred from working for his country ever again. To protest, he founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, and he became the first openly gay man to testify in Congress on behalf of the homosexual minority, the first to protest at the White House to call for the end of the gay purges, and the first to declare—first in his legal writing, and later on a picket sign—that to be gay was morally good.

Kameny kept virtually every letter he ever sent or received—tens of thousands of them. Shortly before he died, he sold his vast collection of personal papers, which the Library of Congress now holds in the Madison Building: letters, notes, meeting minutes, and legal files.

If these documents were piled on top of one another, the stack would rise taller than a six-story building. I’ve spent the past seven years—first as an undergraduate, then as a PhD student—digitizing and analyzing these documents for the first time. They now form the backbone of my forthcoming book, The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. the United States of America, which follows Kameny in an astonishing series of unprecedented fights against the U.S. government.

I’ve also spent the past several years researching the national context of Kameny’s story: I researched the stories of queer Black activists like Bayard Rustin, who influenced Kameny’s own strategy. I unearthed thousands of recently declassified legal transcripts and government documents, including a 1,000-page FBI file that details the government’s surveillance and infiltration of Kameny’s organization. And I examined archives to understand the stories of other LGBTQ activists in New York and California, including trans heroes like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. From these documents, and from dozens of hours of personal interviews with surviving activists of Kameny's era and beyond, I pieced together a long-hidden picture of the diverse and interconnected struggle for LGBTQ equality.

For a historian, there’s no better feeling, after combing through thousands of documents, than discovering one that changes how we understand our past. It’s my hope to make that feeling available to anyone. For this reason, I’ve made over 117,000 pages of LGBTQ historical documents available online at The Deviant’s Archive. The Deviant’s War is almost entirely predicated on the documents in this collection, and other stories are almost certainly hidden in their pages.

Below are 10 of the most revelatory documents I found. They offer just a glimpse of Frank Kameny’s war against the United States federal government, and a picture of the wider pre-Stonewall struggle against federal interrogators, bigoted congressmen, and the FBI—a fight that grew throughout the Sixties and exploded in scale after Stonewall. Their struggle continues today, and knowing the history of our movement allows us to learn from their successes and mistakes as we continue fighting.

ALL COLLAGES BY HUNTER FRENCH | IMAGES COURTESY ERIC CERVINI

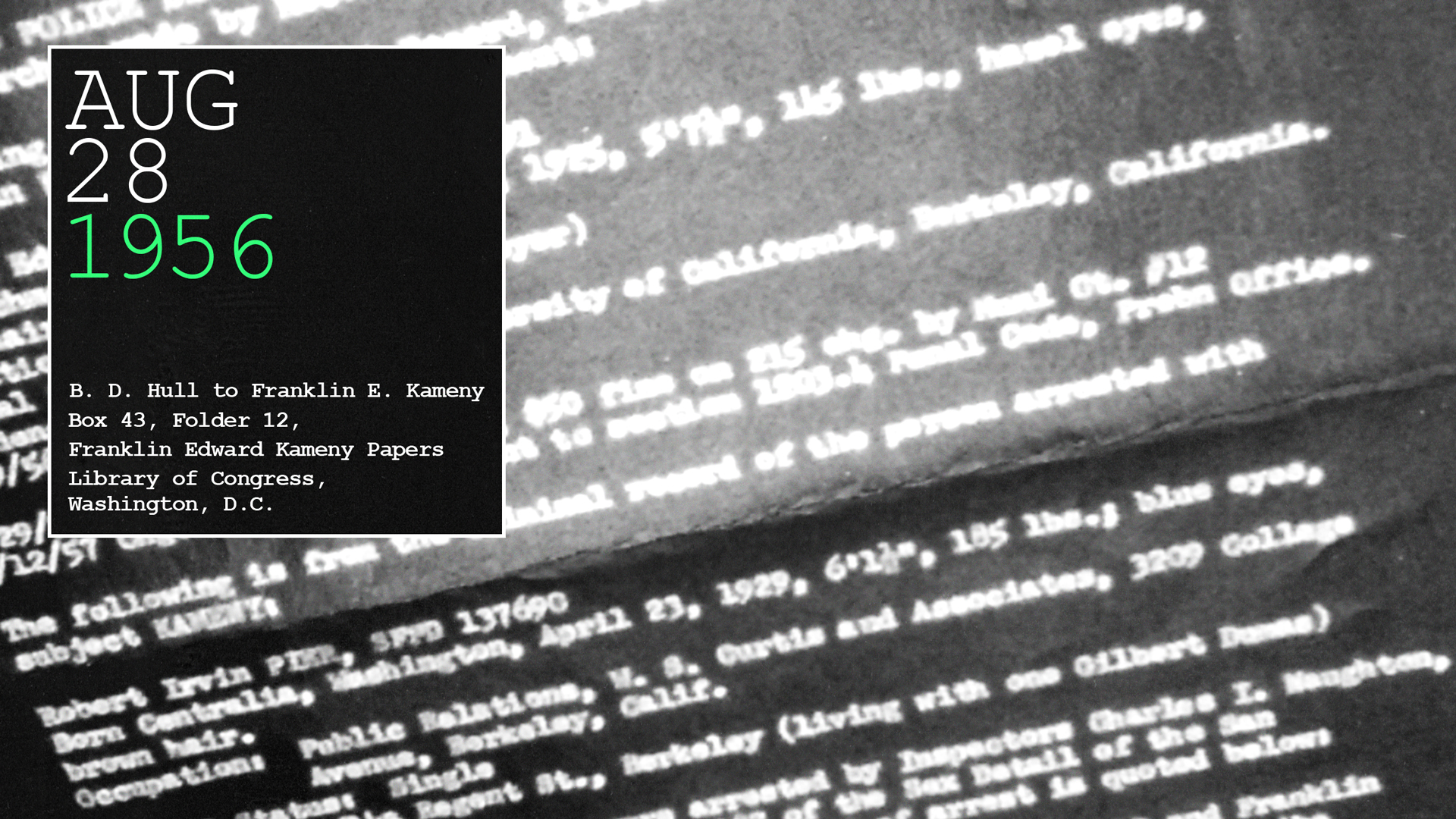

In 1956, Dr. Franklin E. Kameny’s future looked exceedingly bright. The young astronomer was known as a sardonic man who seldom made mistakes; he had just graduated from Harvard with a PhD in astronomy. The Space Race, the competition between the US and the Soviet Union to reach and dominate outer space, was beginning. The government desperately needed scientists like Kameny to develop the technologies that would allow America to travel to space. But during an astronomy conference in San Francisco, Kameny was arrested in a San Francisco public restroom with another man—two police officers had spied on the restroom from the ceiling, watching the pair from behind a ventilation grill. Sixty years later, I found the police report in Kameny’s papers at the Library of Congress.

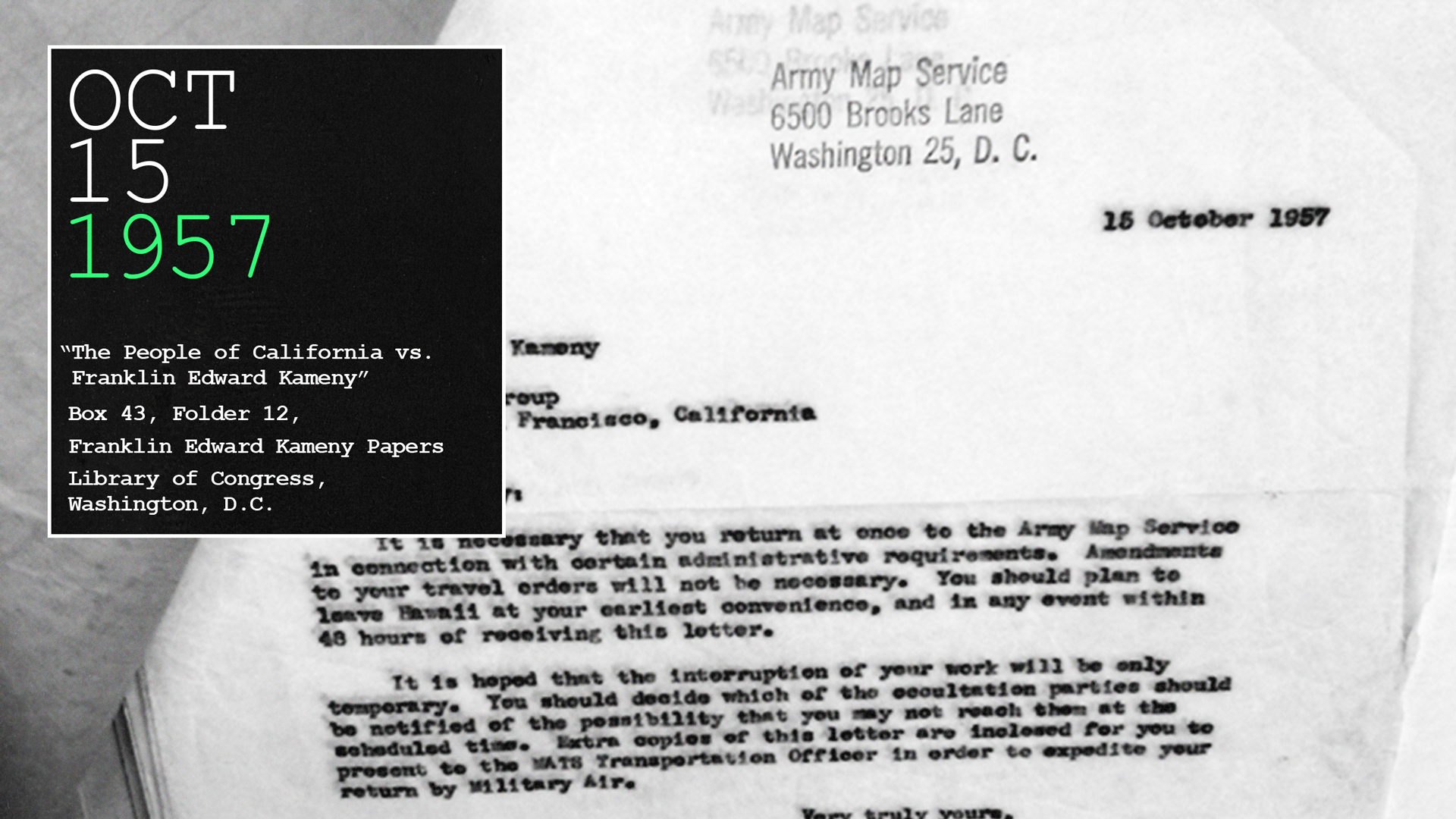

A year after his arrest, Kameny was working on a Department of Defense project in Hawaii when he received this letter. The Civil Service Commission (CSC), the governmental bureau responsible for determining whether federal workers were suitable for federal employment, had discovered Kameny’s arrest record. The government summoned Kameny immediately to Washington, marking the beginning of his first battle against the gay purges.

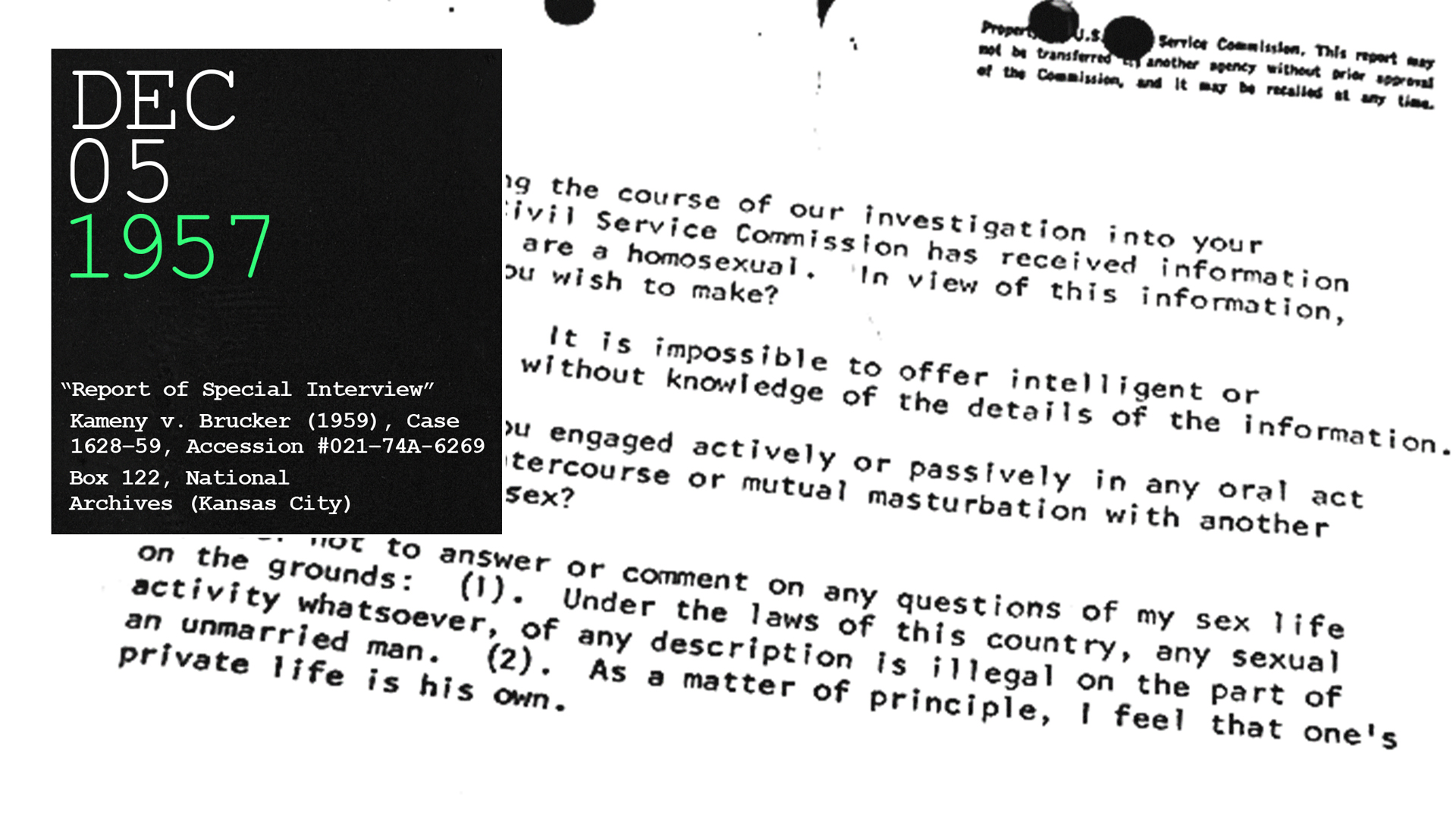

After weeks of uncertainty, CSC subjected Kameny to a series of humiliating interviews. The interrogators asked him repeatedly about his sex life: “Dr. Kameny, have you engaged actively or passively in any oral act of coition, anal intercourse, or mutual masturbation with another person of the same sex?” Each time, Kameny refused to answer. This transcript was especially difficult to find: After searching for the record in archives across Washington, I finally tracked it down to a federal storage facility in Kansas City. I was lucky to be able to find them: hundreds of thousands of other documents like this one, including those inside the FBI’s massive Sex Deviates file––collected by then–FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in his surveillance of LGBTQ Americans––have been destroyed, likely to cover up countless invasions of privacy.

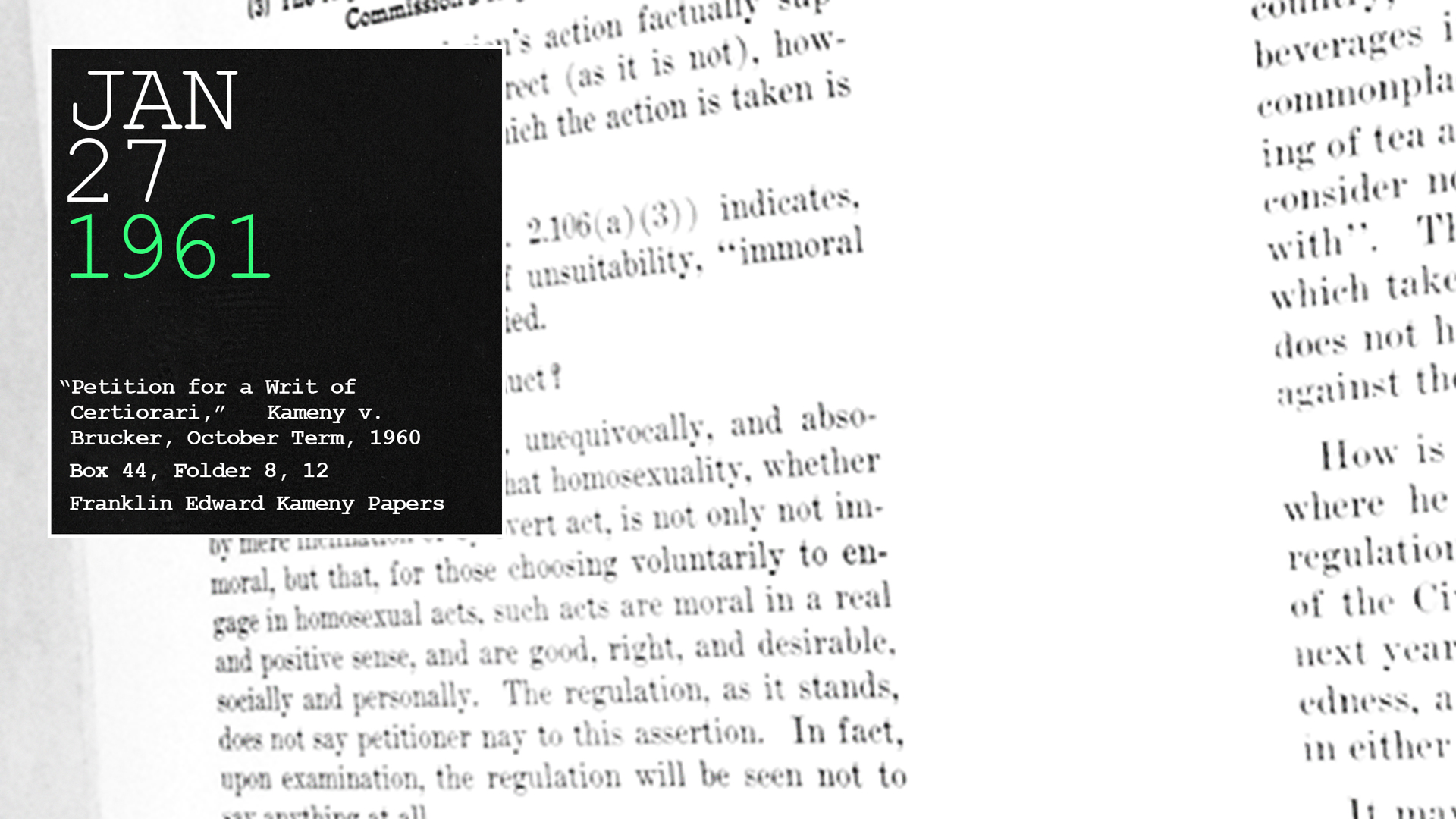

At first, Kameny thought that he’d be able to explain himself out of the situation. He argued that the San Francisco arrest had been a misunderstanding. The government fired him nonetheless, claiming he had falsified a government document when he had admitted his arrest was for disorderly conduct rather than lewd behavior and loitering. Kameny was forever barred from working in the aerospace industry. Thrust into poverty, Kameny fought back: He became the first openly gay man to petition the Supreme Court for LGBTQ equality. He wrote his brief, which simply requested a trial, without an attorney, and the document became a revolutionary manifesto for gay rights. In its most significant passage, Kameny declared that homosexuality was not immoral, as the government claimed, but morally good. A decade before Stonewall Riots, Kameny was declaring his pride.

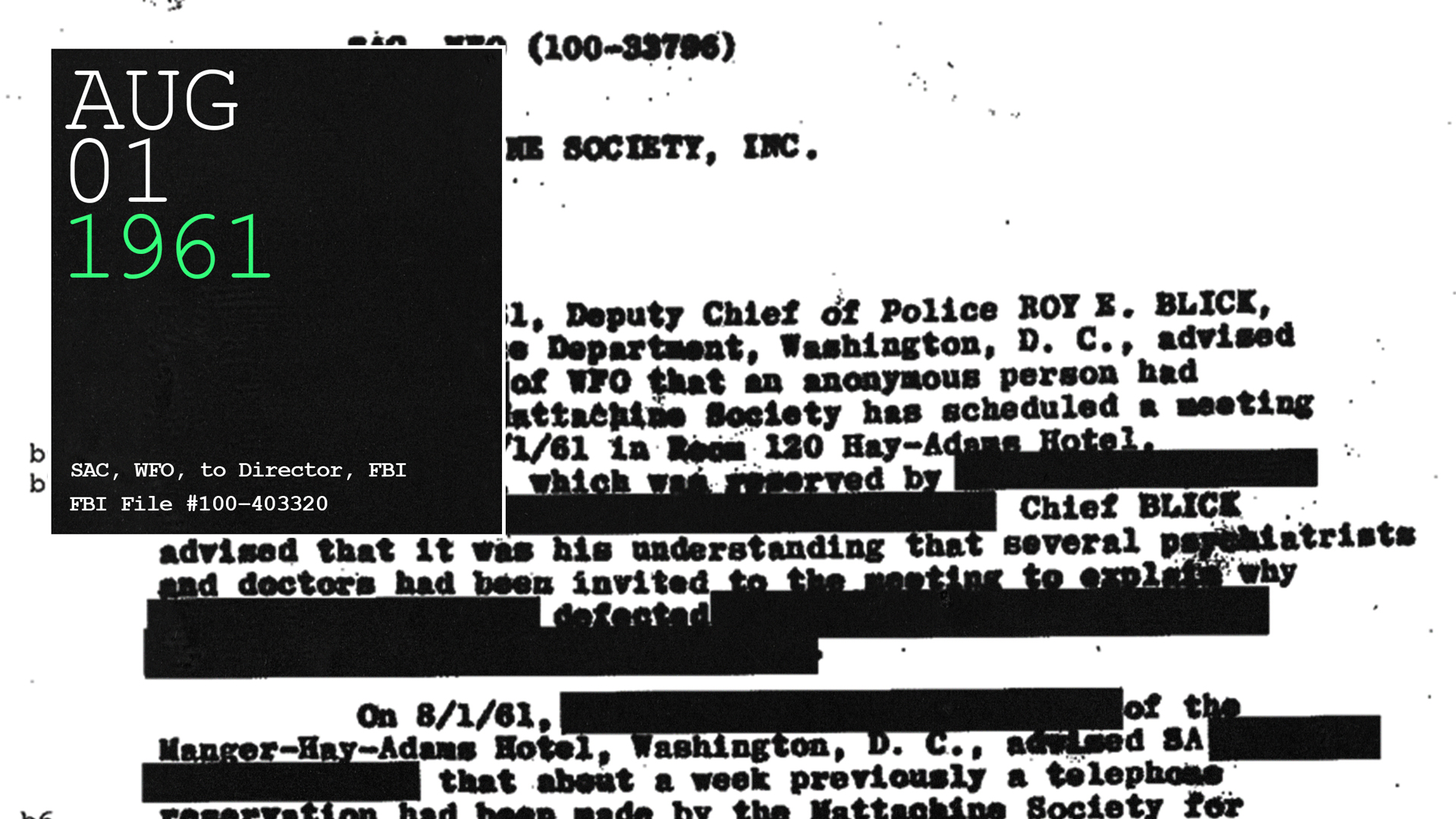

After Kameny's Supreme Court effort failed, he turned to organizing. He and 15 other gay men met in the Hay-Adams Hotel in Washington, directly across from the White House, to create a new organization of homosexuals: The Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW). The 16 men, dressed in business attire, discussed by-laws and the dry logistics of building a new organization. But the FBI was listening. According to a recently declassified 1,000-page FBI file, the hotel manager eavesdropped on the meeting and reported back to the FBI, and the meeting's summary went straight to J. Edgar Hoover's desk.The Bureau learned that homosexuals—who, in the government’s eyes, were national security risks—were organizing only a few hundred feet from the White House.

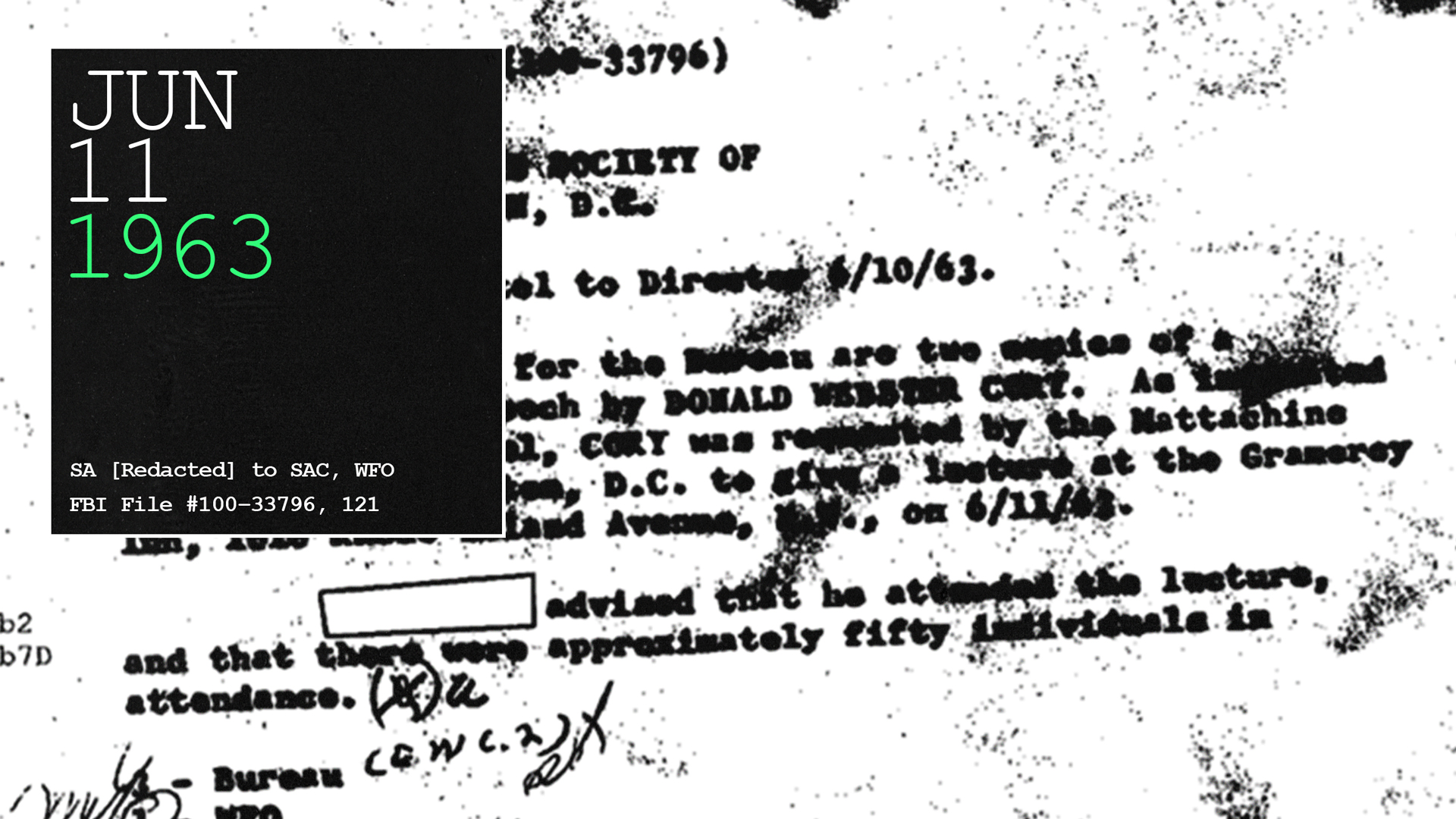

After cross-referencing the FBI file with Kameny’s personal papers, I made a startling discovery: The FBI successfully recruited an informant within the Society, and this individual handed a list of dozens of alleged homosexuals over to the FBI. Several careers—several lives—were likely ruined. The extent of the infiltration, including the informant’s motivation for betraying his fellow homosexuals (another Mattachine member had cheated on him) has never been revealed before. And in this document, the FBI reports on the MSW’s first public event: a lecture by pioneering gay author Donald Webster Cory. The informant reported that Cory had merely followed the “party line” of the pre-Stonewall gay rights movement.

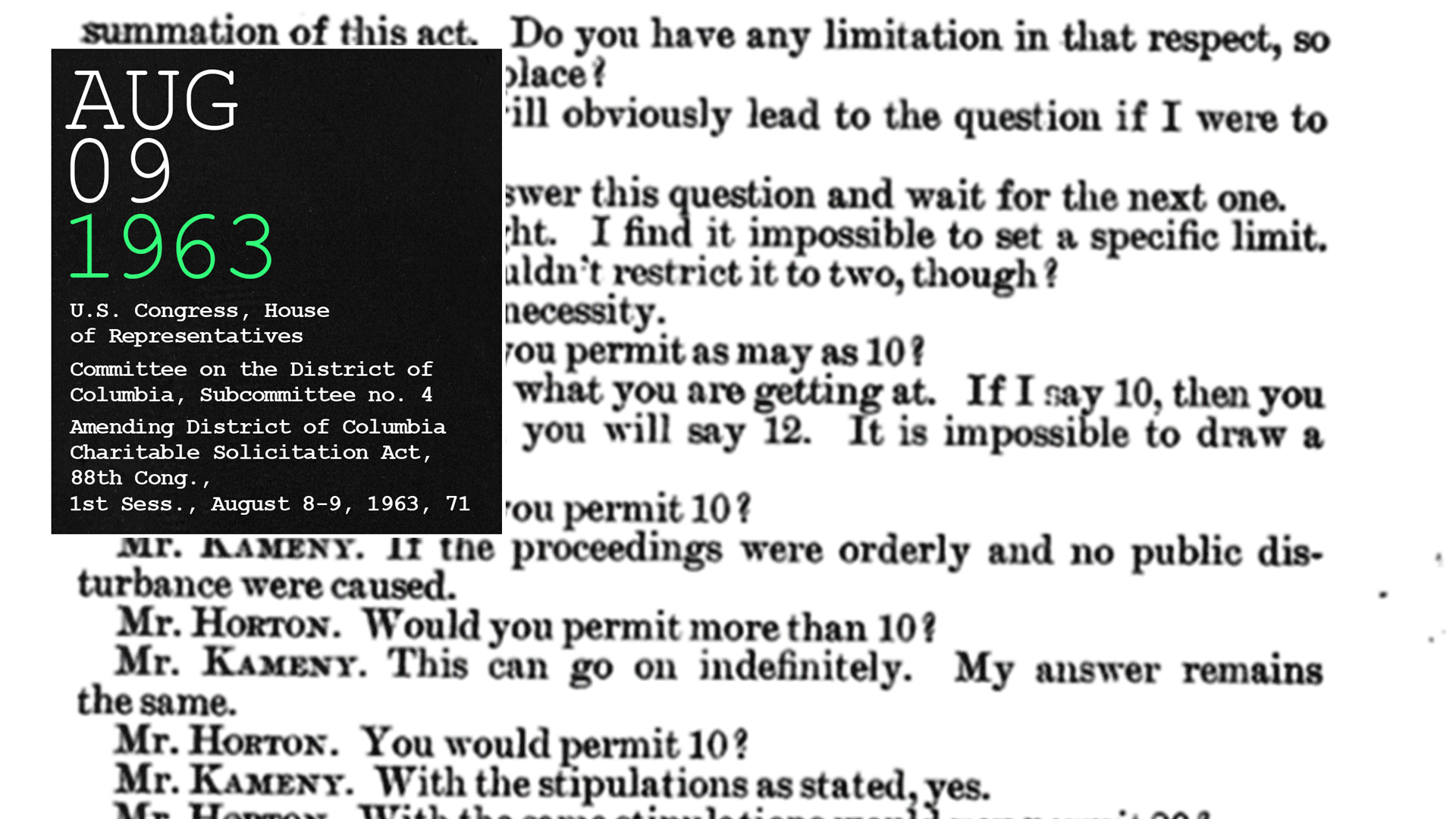

A few months later, a U.S. congressman from Texas, John Dowdy, was enraged to learn about an organization of homosexuals in the District of Columbia and introduced legislation to ban the organization. Frank Kameny, who was still avoiding public declarations of his homosexuality, became the first openly gay man to testify before Congress, defending his organization during a two-day saga of questioning designed specifically to humiliate the witness.

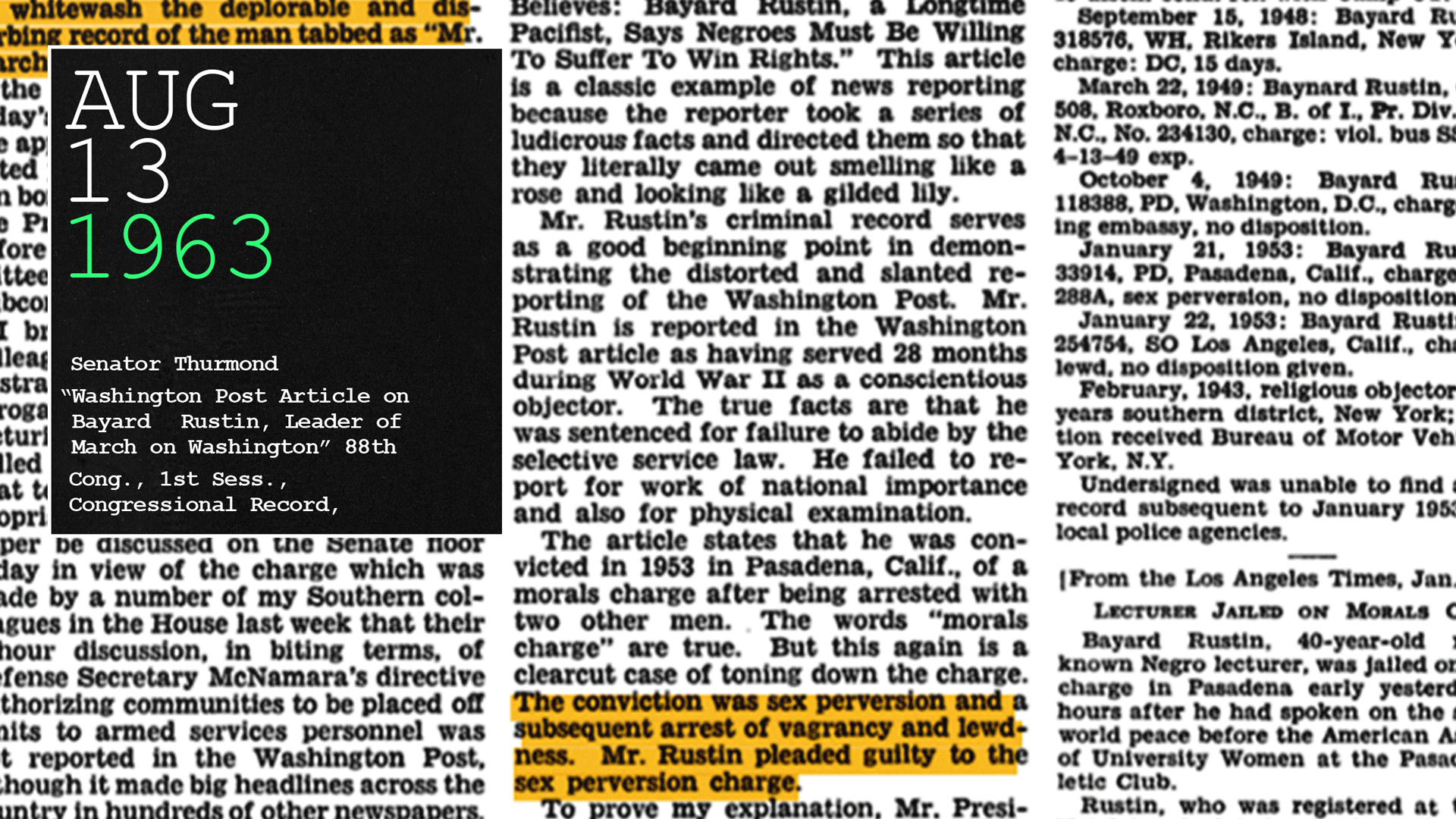

Four days later, Strom Thurmond stood on the floor of the Senate to announce that the organizer of the upcoming March on Washington, Bayard Rustin, was a sexual pervert. The move backfired: The Black Freedom Movement rallied around Rustin, and the March became a historic event: hundreds of thousands of Americans demanded action on racial inequality from the federal government, which then enacted the 1964 Civil Rights Act. At the March, Frank Kameny stood in the crowd, listening to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech alongside a delegation of gay members of Mattachine Society of Washington. Almost immediately after the march, the FBI received intelligence that homosexuals, inspired by the event, intended to begin demonstrating themselves, something that had never been done before.

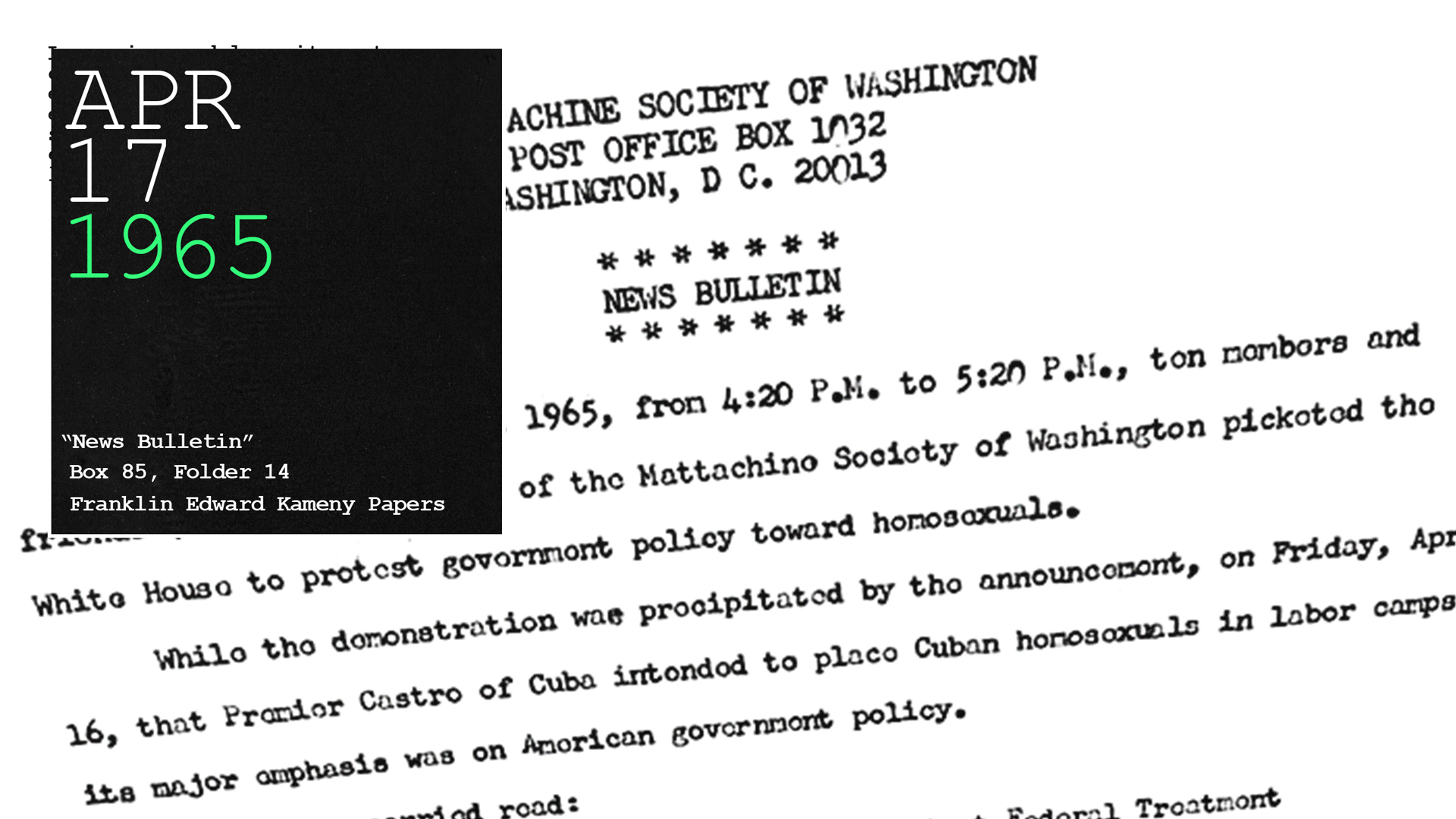

Early in my research, I was surprised to learn that the Society organized its first demonstration in Washington in front of the White House as a response to news from Cuba: Fidel Castro’s government had announced plans to send sexual deviants to labor camps. At this historic march, seven men and three women (all white) marched silently in a circle, comparing Cuba’s policies to those of the United States. To project professionalism and respectability, Kameny demanded that all of the demonstrators wore suits or dresses. But the press, distracted by a massive anti-war march the same day, ignored the pro–LGBTQ rights protest. The protestors resolved to march once again.

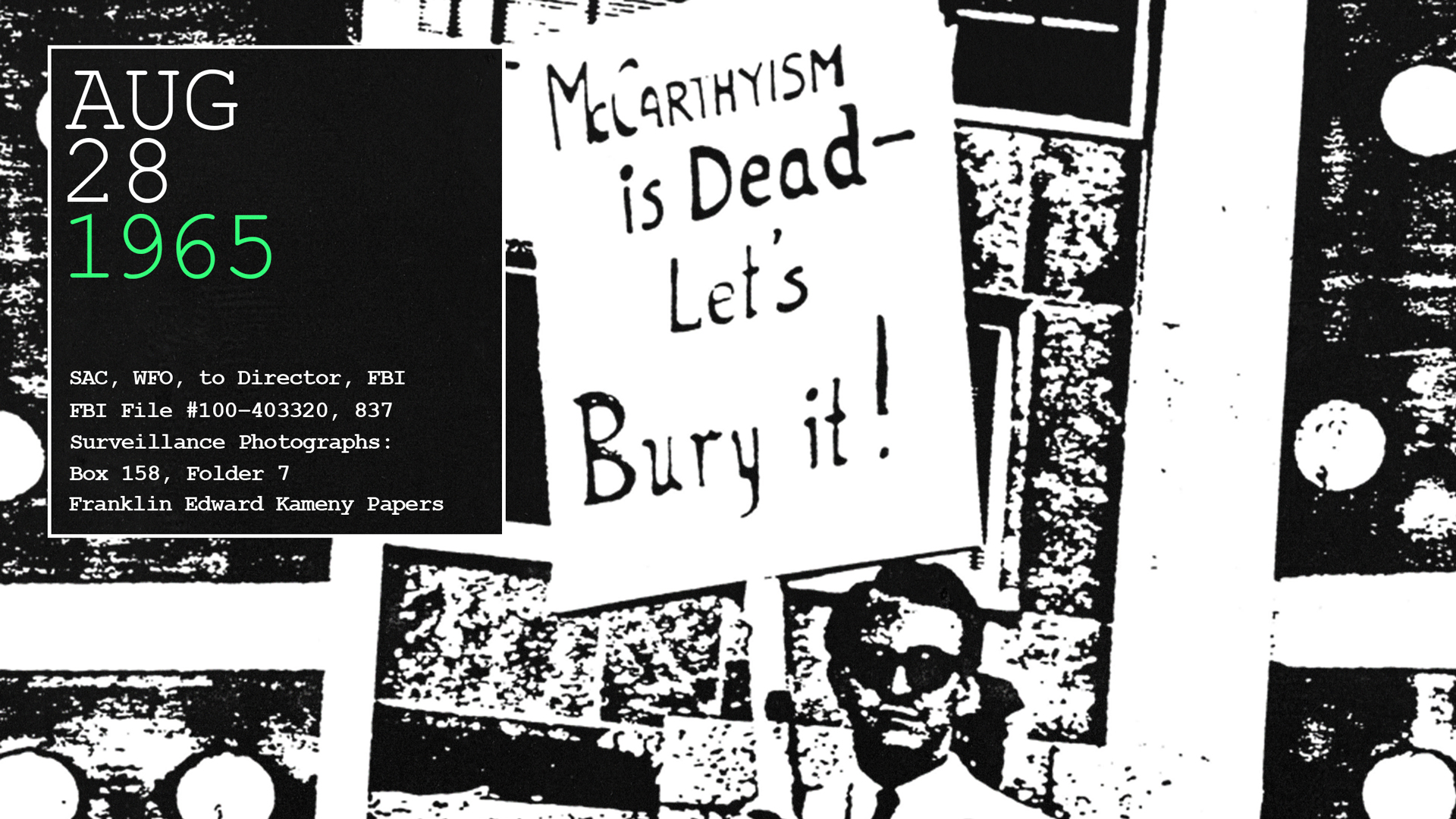

There are 23 photographs in my book, and this one is my favorite. At a Mattachine demonstration in front of the State Department protesting the gay purges, federal investigators were watching. By photographing license plates, faces, and picket signs, the investigators hoped to identify the homosexuals and remove them from their federal jobs. The marchers knew this, but marched nonetheless. In this photograph, you can see a demonstrator staring straight into the camera. The activists continued marching each Fourth of July until 1969, when Stonewall changed everything. Within months, the annual marches had transformed into a new tradition: a holiday called Pride. T

The Deviant’s Archive includes 117,000 additional documents, ranging from radical lesbian newsletters to interrogation transcripts from inside the Pentagon, and I reference only a fraction of them in the book. I hope that this “open sourcing” of history will inspire other scholars, whether they’re trained historians or curious members of the LGBTQ community, to continue unearthing hidden parts of our past—in this collection, and in other archives across the country. Today’s America teaches us that we can’t afford to forget the lessons of the past: how to be vigilant, how to work together, and how to fight back. But we have to search for those lessons first. Then, we have to share them with the world.

Comments