WasThomas Barrow on "Downton Abbey" Correctly Portrayed As a Gay Man Of That Era?

Fifty-seven minutes into the first episode of Downton Abbey, the fastidious, sharp-featured footman Thomas Barrow makes his move, confronting his erstwhile summer lover—the impoverished (but entitled) Duke of Crowborough—with epistolary evidence of their affair. Barrow has all the coiled menace of a spiteful child, a weak sort of strength that only kicks when you’re down.

The Duke, on the other hand, is louche and unctuous, the human personification of privilege lounging in a fabulous dressing gown. Their short tete-a-tete is a gem of a scene, their body language forecasting the inevitable: the attempted blackmail fails, and three minutes later, Barrow watches his letters burn, taking with them his imagined future as the Duke’s valet and lover.

It’s a bold move—for Barrow, sure, but more so for Downton Abbey. With one short scene, creator Julian Fellowes made a declaration: the love that dare not speak its name would be given a voice here. Goodbye to veiled intimations and Significant Looks; goodbye to fusty, dusty “confirmed bachelors” and “spinster” aunts; goodbye to the historical closet and your mother’s Masterpiece Theatre.

Hello to the future of the gay past.

“I think what we've done with Thomas in the story is tried to reflect how scary it was,” says Alastair Bruce, who worked as the historical advisor to the show, and is reprising that role with the new Downton movie, in theaters September 20. In the film, audiences will see Barrow in the context of a wider gay world for the first time: visiting a secret gay bar, dodging police harassment, and possibly even finding love.

It’s an exciting tale set in an exciting period. The post-Edwardian moment—Downton Abbey opens in 1912, with news of the sinking of the Titanic; the movie takes the story all the way up to 1927—was an era of tremendous upheaval in Western culture. World War I was still “the war to end all wars,” the Roaring Twenties were ratcheting up to the Great Depression, and the last vestiges of Victorianism were being thrown out the Overton window. A rejection of the past was so fundamental to this period that we still refer to the artistic flourishing of this moment as “Modernism,” despite it now being 100 years ago.

All of them, that is, except for Thomas Barrow. Barrow is instantly recognizable as a modern gay man, even if he never quite uses those words. From isolation to conversion therapy, his struggles are our struggles, just in period drag. On the one hand, this feels like an elaboration of that famous gay liberation slogan “we are everywhere,” expanding it to be “we were everywhere” also. On the other hand, it seems to remove sexuality from the domain of history entirely, suggesting that the experience of being gay has always been the same, no matter the place or period. This helps to explain why, after such a strong start, Barrow’s storyline in Downton Abbey largely fizzles out: he has nowhere to develop. While everyone else in the show becomes, Barrow already is.

The question for queer Downton Abbey fans, then, is this: Is Thomas an accurate unveiling of historical homosexuality, hidden but fully formed, just waiting for us to notice his existence? Or is he a backward projection of our current idea of what it means to be gay, an anachronism disguised as a revelation?

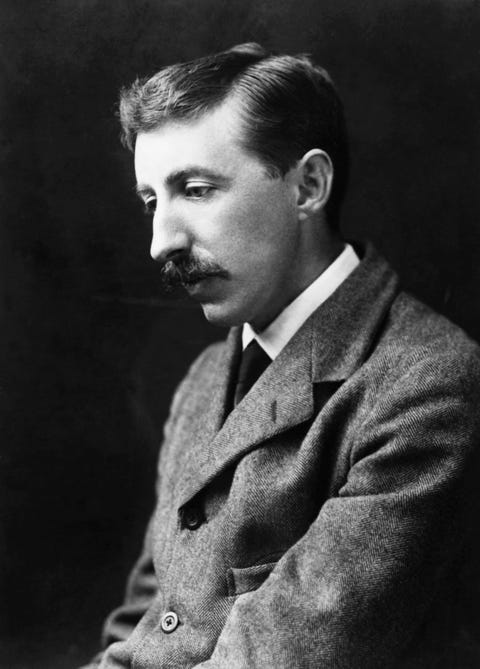

The most obvious point of reference for Barrow’s character can be found in E. M Forster’s Maurice. Forster, born on New Year’s Day, 1879, documented the emergence of modern England through the foibles and failures of those that lived (like Forster himself) on the outskirts of the upper-class.

Maurice, his most autobiographical book, was written in 1914. It follows its titular protagonist, Maurice Hall—“a mediocre member of a mediocre school”—as he discovers his desires for other men. After an abortive and agonizing affair with a fellow student from his own upper-class milieu, Hall meets Alec Scudder on a visit to his ex’s estate. The affair between Scudder and Hall races forward, moving quickly through break-up and blackmail before delivering the happy ending that was Forster’s raison d’etre for writing the book in the first place. Like Thomas Barrow, Alec Scudder seems preternaturally gay, fully aware of his sexual desires, that they are exclusively for men, and that they mark him, irrevocably, as a different sort of person.

Maurice, his most autobiographical book, was written in 1914. It follows its titular protagonist, Maurice Hall—“a mediocre member of a mediocre school”—as he discovers his desires for other men. After an abortive and agonizing affair with a fellow student from his own upper-class milieu, Hall meets Alec Scudder on a visit to his ex’s estate. The affair between Scudder and Hall races forward, moving quickly through break-up and blackmail before delivering the happy ending that was Forster’s raison d’etre for writing the book in the first place. Like Thomas Barrow, Alec Scudder seems preternaturally gay, fully aware of his sexual desires, that they are exclusively for men, and that they mark him, irrevocably, as a different sort of person.

On the surface, this feels like incontrovertible proof of Downton’s historical accuracy. But when Forster wrote Maurice, he’d never had a relationship with another man, and he wouldn’t until midway through World War I, when he was 38 years old. “He imagined these things well before he experienced them,” agreed Moffatt, Forster’s biographer. Yet the book is often used as period research.

“It’s much easier just to look at some medical texts and maybe some literary ones, rather than do the difficult task of working out what people really thought,” said Professor Alison Oram, who led the initiative Pride of Place: England’s LGBTQ Heritage, which documented queer historical spaces for the British government.

In particular, literary research can substitute the experiences of the upper class for those of all people. In the post-Edwardian period, upper-class men were more likely to already understand the world in terms of heterosexuals and homosexuals, with a bright and absolute line dividing the two. But for working-class men like Thomas Barrow, same-sex desire didn’t necessarily preclude having an otherwise “normal” existence, often including relationships with women.

When Forster himself did, finally, embark upon a sexual relationship, it was with an Egyptian man named Mohammed el-Adl. Like Alec Scudder and Thomas Barrow, el-Adl was young and working class. But whereas Scudder and Barrow seemed to think of themselves as gay, el-Adl experienced his desire for men differently. He was worried about being caught but didn’t have the kind of existential, what-does-this-mean-about-my-identity crisis that we in the West associate with same-sex behavior. Soon after he and Forster met, el-Adl married a woman (for whom he had romantic feelings), but it didn’t curtail his relationship with Forster.

Forster was keen to get al-Adl to understand sexuality, and sexual orientation, in the same way that he did: An unconscious extension of the broader colonial project of reshaping the world in the image of (aristocratic) England. Over time, British customs would obscure and eventually replace the thousand years of Middle Eastern history celebrating (some kinds) of sex between men, another example of “modernity” being born in this period.

But while El-Adl’s desires might have seemed strange to Forster, they would have been fairly recognizable to another group: working-class Brits. In the post-Edwardian period, “there could be greater accommodation of same-sex desires and same-sex acts in working-class communities,” says Professor Justin Bengry, a cultural historian of queer sexuality in England.

The Labouchere amendment of 1885 made “gross indecency”—a.k.a. sex between men—a crime, and was used to prosecute Oscar Wilde. It was a forerunner to the kinds of police repression that Barrow encounters in the new Downton movie. But in popular understanding, being a “criminal pervert” wasn’t necessarily about the sex you were having. It was about how well you lived up to the expectations of your gender, if you wanted a married life, and if you were otherwise respectable.

The most highly visible queer people in this period would have been those who openly defied gender norms. Even when it came to the prosecution of Wilde, much was made about his aesthetic and dandified existence, which mocked traditional manhood.

The most highly visible queer people in this period would have been those who openly defied gender norms. Even when it came to the prosecution of Wilde, much was made about his aesthetic and dandified existence, which mocked traditional manhood.

But for masculine, working-class men, wanting sex with men “didn’t necessarily question their sense of themselves as virile or ‘normal,’” said Dr. Bengry. According to historian Matt Houlbrook’s Queer London, this is the “central difference between the sexual landscape of interwar London and the present day.”

To a 21st century ear, this might sound surprising. But we have to remember the context in which these men were raised. The Victorian world was cleft in twain, with men on one side, and women on the other. The divide between them was imagined as vast and almost insurmountable. Outside of their immediate families, men were expected to spend most of their time with other men; women, with other women. Romantic and intense same-sex friendships were de rigueur. Heterosexual marriage obviously had sexual dimensions, but it was also a deeply practical institution, the main unit of economic production in the country, and the only insurance against the vagaries of old age.

As Victorian ideals receded from dominance—as cross-gender friendships became more common, as marriage became more companionate, as urbanism and greater social mobility created economic possibilities outside the family—the men and women who still had intense friendships and bloodless marriages began to seem strange. Increasingly, sexologists, politicians, and writers began to promulgate the idea that these behaviors were signifiers of homosexuality, to be surveilled and curtailed.

Forster never did edit Maurice, however, and his hard-won knowledge of the complexities of the human heart (amongst other organs) died with him. As decades passed, the neat fiction of binary sexuality became broadly acknowledged “truth,” leaving less and less space for middle-dwelling, working-class men like Buckingham and el-Adl.

From an earlier and earlier age, people would be taught—in streets as much as in schools—that homosexuals existed, that they were unlike other men and that any apparent “middle ground” was actually a slippery slope headed straight to hell.

All of which brings us back to Thomas Barrow and the new Downton Abbey movie. Barrow might have been an implausible outlier at the beginning of the show in 1912, but by the 1950s, working-class men who identified as homosexual were thronging the streets of London. We may never get to see that learning process happens for Barrow (unless there’s a Downton Abbey sequel planned; fingers crossed), but at long last, in the new film, we’ll get to see a world in which it could.

Comments