The Supreme Court Guided By Principles of Justice or The Principles of Their Politics?

BY

Three explosive cases are about to test whether conservative Supreme Court justices are seen to rule according to their professed legal principles—or their politics.

On October 8, just day two of the new term, the Court will hear arguments questioning if the federal law that prohibits workplace discrimination "because of...sex"—Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964—applies to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Millions of Americans' rights are at stake. About 4.5 percent of the adult U.S. population identifies as gay or lesbian—about 11.3 million people—according to a recent Gallup poll. Another 1.6 million are transgender, estimates a friend-of-the-court brief submitted by 82 scholars who study that population. Though 22 states have enacted their own laws barring discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and/or gender identity, 28 have not, meaning that about 44 percent of the LGBTQ population relies solely on Title VII for workplace protection.

Interest in the case extends far beyond the LGBTQ community itself. More than 1,000 outside organizations and individuals have weighed in via more than 70 friend-of-the-court briefs. Among those supporting LGBTQ employees are more than 200 major corporations (including Apple, General Motors, IBM and State Farm), all the major unions, the American Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the American Medical Association. The defendant employers, in turn, count among their supporters the Conference of Catholic Bishops, the National Association of Evangelicals and privacy groups whose members fear having to use the same bathrooms as members of the opposite biological sex. The Trump administration's Justice Department and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission are also backing the employers in these cases, and U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco's office will take part in the oral arguments.

At a time of profound skepticism about the Court's claims of nonpartisanship, its approach to these cases will be scrutinized for signs of political bias. The Republican Senate's blanket refusal to permit Democratic President Barack Obama to appoint any successor after the death of conservative Justice Antonin Scalia in February 2016 thrust the Court's partisan underpinnings into a harsh, undeniable light.

The damage was exacerbated when, as the 2016 presidential election approached, several prominent Republican senators pledged to try to deny Democrat Hillary Clinton any Supreme Court appointments if she won. Just last month, four Democratic U.S. senators, led by Rhode Island's Sheldon Whitehouse, filed an extremely unusual friend-of-the-court brief in a gun-control case baldly asserting that "the Supreme Court is not well," that "the people know it," and hinting that the Court may need to be "restructured to reduce the influence of politics." As if that wasn't enough, a recent book excerpt published in The New York Times, corroborating accusations of collegiate sexual misconduct by now-Justice Brett Kavanaugh (which he categorically denied at the time), has revived the partisan rancor surrounding last year's confirmation hearings and led some Democratic presidential candidates to call for his impeachment.

Since Kavanaugh was sworn in last October, replacing swing-vote Justice Anthony Kennedy—a more moderate conservative and strong champion of LGBTQ rights—Republican-appointed conservatives have commanded a solid five-person majority on the nine-justice court. Looking just at the presumed ideological proclivities of the justices, the LGBTQ employees in these cases might be assumed to face an uphill battle.

Associate Justice Antonin Scalia

But cases aren't supposed to be decided by ideology. In cases like these, justices say they ground their decisions on the text of the statute in question and the precedents interpreting it. For at least 20 years, conservative jurists, led by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, have championed a doctrine of statutory interpretation called "textualism," which purports to provide an objective decision-making methodology that transcends ideology. It hinges on the plain meaning of a statute's words, rather than on the subjective intent or expectations of the legislators who enacted it.

Those rules now dictate an outcome in favor of the LGBTQ employees, they and their allies insist. "This is a moment of truth for textualists," Yale Law School professor William Eskridge Jr. said. "It's either put up or shut up." Eskridge co-authored a friend-of-the-court brief supporting the employees. "Either give Title VII's text and structure the effect its breadth demands or admit that textualism does not free statutory interpretation from ideology."

Four former U.S. solicitor generals sounded the same theme in their own brief, co-authored by constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe of Harvard Law School. "These cases are simpler than they seem," Tribe wrote. "Here, all that is necessary to decide the questions presented is a direct application of textualist principles to the plain language of Title VII." Tribe wrote on behalf of Walter Dellinger III (acting SG under Bill Clinton), Seth Waxman (SG under Clinton), Theodore Olson (SG under George W. Bush) and Neal Katyal (acting SG under Barack Obama).

The employers and their allies respond that the 1964 law was obviously never intended to address these forms of alleged discrimination, that Congress has repeatedly rebuffed invitations to amend the law to do so and that the employees are, therefore, effectively inviting the Court to rewrite that law by illegitimate judicial fiat. "Federal courts should not usurp Congress's authority by judicially amending the word 'sex' in federal nondiscrimination law to include 'transgender status,'" writes John J. Bursch, vice president of appellate advocacy for the conservative nonprofit Alliance Defending Freedom, which represents R.G. and G.R. Harris Funeral Homes, the employer accused of discriminating on the basis of gender identity in one of the three cases to be argued. (ADF describes itself as advocating "for the right of people to freely live out their faith.")

"For more than 40 years," assert Justice Department lawyers in their brief supporting the employers accused of discriminating against two gay employees, "Congress has repeatedly declined to pass bills adding sexual orientation to the list of protected traits in Title VII." ("What Congress hasn't done shouldn't affect the interpretation of the statute," responds American Civil Liberties Union staff attorney Gabriel Arkles. "It should be interpreted for what it says." The ACLU is co-counsel for two of the three plaintiffs in these cases, Donald Zarda and Aimee Stephens.)

The Softball Player, the Skydiver, and the Funeral Director

Courts do not decide legal issues in the abstract; they address questions presented to them in specific lawsuits. So before diving into the evolution of the law and the parties' particular arguments, it is crucial to examine the facts of the particular cases before the Court.

There are two involving sexual orientation (those of Zarda and Gerald Bostock), which have been consolidated and will be argued together first, and one involving gender identity (that of Stephens), which will be argued separately immediately afterward.

|

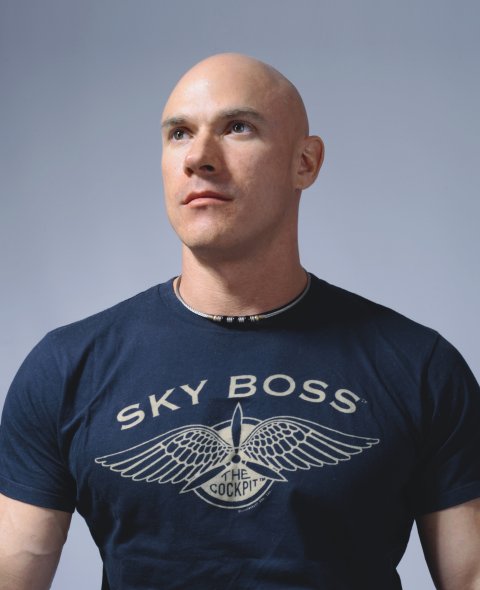

FE_SCOTUS_05

Skydiving instructor Donald Zarda.

JORGE RIVAS

|

In 2003, Gerald Lynn Bostock took a job as a child welfare services coordinator in the Clayton County juvenile court system in Jonesboro, Georgia, near Atlanta. For ten years he compiled an outstanding record, his attorneys claim. In January 2013, however, he started playing softball in a gay association known as the Hotlanta League. This drew criticism, he claims, from people influential with his employer, Clayton County. Three months later the county audited Bostock's unit and, that June, he was fired for "conduct unbecoming of a county employee." The county now claims that Bostock had mismanaged funds. Bostock, now 55, denies the accusation and denounces both the audit and its findings as phony excuses manufactured to hide the real reason for his termination: bias against his homosexuality. Bostock is appealing a ruling of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, in Atlanta, which affirmed the pretrial dismissal of his suit on the grounds that Title VII did not bar discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Meanwhile, in 2010, Donald Zarda was a skydiving instructor for Altitude Express in Calverton, New York, on Long Island. He often led "tandem" jumps, where he was strapped closely to the customer. That June he was fired for, he was told, having shared "inappropriate information" with a customer "regarding his personal life." Zarda maintained that he told a woman client he was gay in order to dispel the awkwardness of the tight physical contact. Altitude asserts that, after the jump, the woman complained of being "inappropriately touched" by Zarda, and that only then did Zarda mention his sexual orientation. Zarda sued that September. In February 2018, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York ruled that his case could go forward to trial because Title VII prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation. (In October 2014, Zarda, then 44, died in Switzerland while engaged in the extreme sport known as BASE-jumping—diving from a cliff wearing a wingsuit. His executors, however, have continued to press his suit.)

Finally, there is Aimee Stephens.

|

| Transgender funeral director Aimee Stephens.CHARLES WILLIAM KELLY/ACLU |

Then known as Anthony, she was hired as a funeral director in Garden City, Michigan, near Detroit, in October 2007. The employer, R.G. and G.R. Harris Funeral Homes, was owned by Tom Rost, a "devout Christian," according to the employer's attorneys. In late July 2013, while on vacation, Stephens wrote Rost explaining that she had "a gender identity disorder that [she] had struggled with [her] entire life," and had, with the support of her wife, decided to transition to female identity in anticipation of eventual reassignment surgery. When she returned to work, she wrote, she would be using the name Aimee and dressing in a skirt suit, in accordance with Harris Homes' dress code for women. Rost fired her two weeks later, before her scheduled return, explaining that it was "wrong for a biological male to deny his sex by dressing as a woman or for a biological female to deny her sex by dressing as a man," Stephens alleges. Rost also said that customers "don't need some type of a distraction" and that her "continued employment would negate that."

Initially, during the Obama administration, the EEOC took Stephens' case and sued Harris Homes on her behalf. But after Donald Trump took office, the EEOC reversed its position, and it now supports Harris Homes. In May 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, in Detroit, ruled that Stephens' case could go to trial because, in its view, Title VII does bar discrimination based on gender identity.

The Evolving History of the Law

There is no dispute that most of the legislators who wrote and voted for Title VII never envisioned targeting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. In 1964, most states still criminalized homosexual conduct and the term "gender identity" was largely unknown. In the 1970s a consensus arose among the federal circuit courts that Title VII (or other, similarly worded federal anti-discrimination statutes) did not reach sexual orientation cases. Courts also rebuffed the tiny number of gender identity cases that arose.

By the early 2000s, however, the legal landscape had changed. Judges began to reassess earlier assumptions in light of, primarily, two intervening U.S. Supreme Court rulings. In 1989, in the landmark Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins case, the Court decided that Title VII barred discrimination based on sexual stereotyping. There, in denying a promotion to Ida Hopkins, partners at the accounting firm had described her as too "macho" and "aggressive," and had suggested she should learn to "walk more femininely, talk more femininely, dress more femininely, wear make-up, have her hair styled, and wear jewelry." Courts began to consider whether sexual orientation and gender identity cases were simply extreme cases of sexual stereotyping: inappropriately assuming that all men should date women, for instance, or that all people assigned female sexual characteristics at birth should identify as women for the rest of their lives.

The other key, intervening Supreme Court precedent was a unanimous ruling in 1998 authored by Justice Scalia. It was as much a victory for textualism as for Title VII plaintiffs. In that case, Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., a male roustabout on an oil rig complained of severe sexual harassment from other males on the rig, including supervisors. The Court ruled that Title VII barred same-sex sexual harassment, even though such practices were probably not envisioned by anyone in Congress who voted for the law in 1964. "It is ultimately the provisions of our laws rather than the principal concerns of our legislators by which we are governed," Scalia wrote. Later that year, in another unanimous ruling involving a different statute, Scalia re-enforced his textualist approach: "The fact that a statute can be applied in situations not expressly anticipated by Congress does not demonstrate ambiguity. It demonstrates breadth."

In light of these precedents, judges began to see Title VII as reaching more broadly than previously assumed. In the early 2000s, three federal appeals courts allowed transgender plaintiffs to sue based on sexual stereotyping, without deciding whether discrimination based on gender identity itself was forbidden. In 2012, in an administrative case, the EEOC ruled that Title VII did, in fact, protect transgender plaintiffs. In late 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder instructed Justice Department staff to enforce that interpretation as well. In July 2015, the EEOC decided that Title VII also banned discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, reversing its earlier position. Then, in April 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, in Chicago, became the first federal appeals court to rule that Title VII barred discrimination against homosexuals, overruling an earlier precedent. It found that bias against the lesbian employee in that case—stemming from the stereotype that women should date only men—"represents the ultimate case of failure to conform to the female stereotype."

"But for" and "Stereotyping"

The LGBTQ employees in the three cases now before the Court make two main "textualist" arguments. One is the stereotyping argument just described—that discrimination against people attracted to the same sex amounts to the "ultimate" form of sexual stereotyping. The other is known as the "but for" argument. The Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled in the past that an employer discriminates "because of of...sex"—the literal text of Title VII—when it treats an employee "in a manner which, but for that person's sex, would be different." Lawyers for the LGBTQ employees say they obviously meet that test. As lawyers for fired Clayton County employee Bostock put it: "When an employer fires a female employee because she is a lesbian—i.e., because she is a woman who is sexually attracted to other women—the employer has treated that female employee differently than it would treat a male employee who was sexually attracted to women." Thus, but for her sex, she wouldn't have been fired.

Similarly, attorneys for Aimee Stephens, the transgender funeral director, contend: "Harris Homes would not have fired her for living openly as a woman if she had been assigned female sex at birth." Thus, but for her biological sex, she wouldn't have been fired.

The employers respond that both arguments are wrongheaded. The arguments lose sight, they claim, of what was the obvious central goal of Title VII: that an employer did not favor one sex over the other. So long as an employer discriminates against all homosexuals, for instance—i.e., both gay men and lesbians—the employer is not favoring either sex over the other. Similarly, so long as employers discriminate against all transgender employees—those transitioning to men and those transitioning to women—they are not favoring either sex.

Under this view, the LGBTQ plaintiffs are guilty of using a "faulty comparator analysis," to use the technical term used by the employers' attorneys. "[Gay skydiver Zarda] is wrong to compare himself to a heterosexual woman," write attorneys for Zarda's former employer. "Zarda (a man attracted to the same sex) must be compared to a lesbian woman (a woman attracted to the same sex). Because employers that base decisions on employees' sexual attraction would treat both Zarda and the lesbian comparator the same way, the comparator analysis reveals no sex discrimination." Similarly, they argue, "the alleged stereotype in this case—the belief that people should be attracted to the opposite sex—is not a sex-specific stereotype and does not treat employees of one sex worse than the other sex."

It is hard to look at these cases without contemplating what might have been. Had President Obama been permitted to fill the Supreme Court seat vacated by the death of Scalia in 2016 with D.C. Court of Appeals Judge Merrick Garland, the U.S. might be a different place. The liberal-leaning faction of the Court would now own five seats, and the employees' chances of prevailing in these cases would be strong. But Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell famously refused to let Obama have any Supreme Court appointment during the last 11 months of his final term. (Obama won his second term with 51 percent of the popular vote.) "Let's let the American people decide," McConnell said at the time, alluding to the upcoming election.

The people then voted for Hillary Clinton by a margin of 2.8 million votes—48 percent to Donald Trump's 46 percent. But Trump won the electoral college and became president. Trump replaced Scalia with Justice Neil Gorsuch in April 2017.

Even then, the employees in these cases might still have been favored to prevail. At that point, Justice Kennedy was still on the bench, and he had authored many of the trail-blazing decisions expanding LGBTQ rights, including Obergefell v. Hodges in June 2015, concluding that same-sex couples had a federal constitutional right to marry. (Kennedy had been appointed by President Ronald Reagan, who had won 58.8 percent of the popular vote.) But Kennedy resigned in June 2018 and Trump nominated staunch conservative Kavanaugh, approved by the Senate on October 2018.

With Kennedy out and Kavanaugh in, some observers see the LGBTQ employees' prospects in these cases as bleak. Where will they find a fifth vote? Zarda's co-counsel, Gregory Antollino of New York, professes to "feel confident" that the employees' textualist arguments will carry the day with at least one member of the conservative faction. "We believe we can get Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, or [Chief Justice John Roberts, Jr.]" he claims.

But if Antollino is wrong, the chief justice will have a hard time softening the blow to the Court's perceived legitimacy. In the past, he has striven mightily to moderate the Court's rightward shift, in an apparent effort to preserve the institution's aura of being above the political fray. He has crafted miraculous compromises where few had imagined any was possible—most famously when he agreed with conservatives that the Affordable Care Act violated the Constitution's Commerce Clause, yet joined liberals to uphold it under the Taxation Clause.

It's often said that, among the three branches of government, the Supreme Court is unique in that its legitimacy depends on its ability to hold itself above the political fray. Its members are not elected; as a body, the Court has no power to enforce its own rulings, so it is entirely dependent on the goodwill of the other branches to carry out its proclamations. ("It has no influence over either the sword or the purse," as Alexander Hamilton famously put it in Federalist No. 78.) Its legitimacy, therefore, hinges on its ability to persuade us, through force of reason, that its decisions flow from neutral principles and precedents. Justice Scalia spent much of his judicial career trying to craft and enshrine conservative rules of interpretation that he believed would enable judges to do just that.

In this case, the justices may need to decide whether they want to be conservatives in the jurisprudential sense, or in the political one.

→ Roger Parloff is a regular contributor to Newsweek and Yahoo Finance. He has also been published in The New York Times, ProPublica, New York Magazine, and NewYorker.com. For 13 years he was a staff writer at Fortune Magazine

Comments