The People Before us Made it Possible to Have Freedom as LGBTQ

Fifty years ago, the nation’s psychiatrists effectively put gay people’s mental health — and their very place in society — to a vote.

Five months prior, on Dec. 15, 1973, the 15-member board of the American Psychiatric Association had voted unanimously, with two abstentions, that homosexuality should no longer be considered a mental illness.

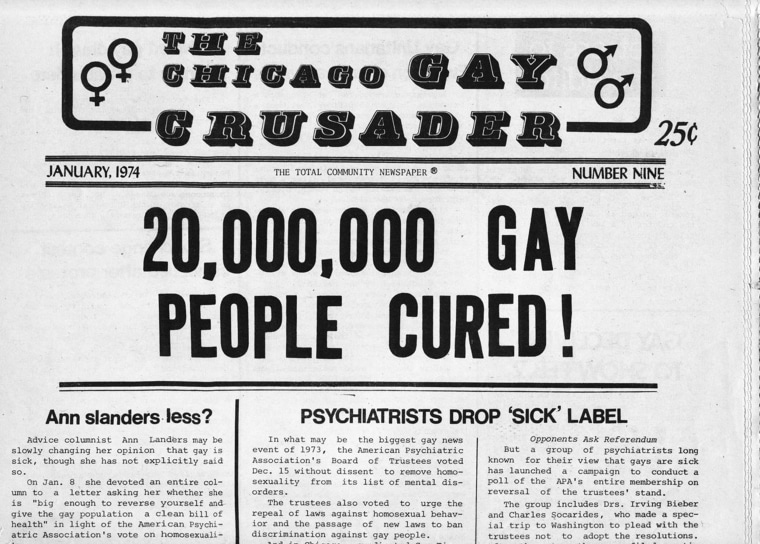

The epochal elimination of the homosexuality diagnosis from the APA’s influential bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, made the front page of The New York Times and The Washington Post. The Chicago Gay Crusader ran the cheeky, if world-weary, banner headline, “20,000,000 Gay People Cured!”

|

But the policy shift was met with dismay by prominent APA members who remained wedded to their conviction that homosexuality was a pathology warranting “reparative” treatment. They prompted a ballot referendum of the organization’s rank and file to repeal the board’s vote.

On April 8, 1974, the APA reported the tally: 58% of the more than 10,000 members to cast a ballot had supported upholding the vote.

Gay people remained “cured.” “It was a sea change in LGBTQ rights,” said the APA’s current president, Dr. Petros Levounis, who as an openly gay man represents a prime product of that change.

Loosening psychiatry’s grip on homosexuality

Those two crucial votes were the culmination of years of both external gay-activist pressure on the APA and an internal reform campaign, fueled by the myriad civil rights movements that bloomed out of the 1960s. These revolutionaries sought to release the repressive grip that Freud-descended psychoanalysis held over postwar American society.

“Psychiatry really set the conditions within which people had to make sense of themselves,” said Regina Kunzel, a professor of history and women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Yale University, referring to the period, from about 1940 through the 1970s, when psychoanalysis dominated the psychiatry field and enjoyed its cultural and political zenith.

Kunzel is the author of a new academic text, “In the Shadow of Diagnosis: Psychiatric Power and Queer Life,” in which she argues that historians have underrecognized psychiatry’s sweeping influence over the perception and treatment of gays and lesbians during the mid-20th century.

The word “power” is littered across the pages of Kunzel’s tidy and at times harrowing account of the mistreatment and torment sustained by gay and gender-nonconforming Americans at the hands of the psychiatric establishment. Psychiatrists, Kunzel asserts, were not merely interested in caring for distressed patients or exerting their influence on the culture at large. They also sought to bolster their own power and authority by proclaiming subject-matter expertise regarding homosexuality and enforcing the heterosexual nuclear family as a Cold War-era bulwark against the existential threat of communism.

“Psychiatry wasn’t just doctors in hospitals, in clinics,” said Kunzel, who sourced copious documentation of gay people being locked in such asylums for years against their will. “They really made bargains with the state to enhance their authority.”

Psychiatrists did so by partnering with the military to weed homosexuals out of the armed forces, and with the criminal justice system to aid in the policing and sodomy prosecutions of gay people. Their pathologizing of homosexuality also influenced the federal government’s campaign to flush gays from the civil service during the Lavender Scare (recently depicted in the limited series “Fellow Travelers”).

This swell of criminalization of gay Americans came in the wake of the Kinsey reports and their bombshell findings. In 1948, Alfred Kinsey published “Sexual Behavior in the Human Male,” shocking Americans with his finding that 37% of men reported a history of sex with other men. The cultural backlash to Kinsey was driven at least in part by psychoanalysts.

As a countervailing anti-psychiatry movement eventually began to take hold, psychiatrists stoked homophobic anxieties with one hand while offering a solution — reparative therapy, also known as conversion therapy — with the other, fueling a feedback loop that bolstered their central and supposedly indispensable place in society.

Gay activism’s ascent thus became dependent on psychoanalysis’ decline. The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, saw the APA’s categorization of homosexuality as a disease as the linchpin obstructing gay liberation.

“Off the couches and into the streets!” became a popular liberationist slogan, emphasizing that gay people were not mentally ill and were a force to be reckoned with.

Psychiatry ‘legitimized a great deal of horrors’

By defining homosexuality as a pathology — the diagnosis appeared in the DSM’s first edition in 1952 — the APA “legitimized a great deal of the horrors,” said Andrew Scull, a sociology professor at the University of California, San Diego, and an expert on the history of psychiatry.

Such horrors, many of which were imposed by coercion or during forced institutionalization in the name of curing homosexual urges and behaviors, included lobotomy, insulin shock, what’s now known as electroconvulsive therapy, and aversion therapy treatment (including the use of emetics and electric shocks, including to the genitals).

One company that made shock therapy devices even had a regular booth at the APA’s annual conference.

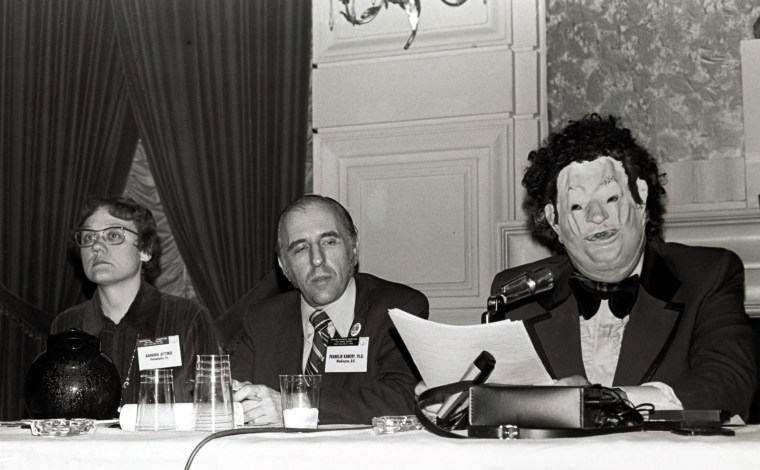

In 1970, the year after the Stonewall uprising, infuriated gay activists began infiltrating these conferences and raucously demanding an end to such mistreatment and the delisting of homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder. In 1972, a gay psychiatrist stunned conference attendees when he appeared on a panel anonymously — dressed in an oversized tuxedo, a ghoulish mask, and a wig — and spoke of the anguish of working in the profession from within the closet.

|

During this same period, Kunzel writes, the APA top brass was seeking to defend psychiatry as an evidence-based science in the face of mounting attacks on the field’s legitimacy. So when gay advocates presented to the organization newer research suggesting that homosexuality was not a sickness but a normal variant of human sexuality, they found a receptive audience among key APA leaders.

“Organized psychiatry was scuttling for safety,” Dr. Richard Pillard, who at the time was a young APA member and a very rare openly gay psychiatrist, recalled in “Cured,” a recent documentary about this moment in the organization’s history.

Dr. Lawrence Hartmann’s APA membership also dates back to that era. Speaking about the appeals he and others made to the organization’s leadership to reconsider its stance on homosexuality during this historic window, he said: “It took some persuading. Sometimes science and politics can cooperate.” Even as he remained professionally in the closet, Hartmann in 1970 helped found what became an influential group of APA members who sought to reform and modernize the organization and make it more responsive to the array of recent sociopolitical upheavals.

Hartmann recalled his crucial efforts to master the bylaws and byzantine bureaucracy of the APA. He marshaled through the proper internal channels a position paper he had written with Pillard arguing for the APA to remove homosexuality from the DSM and become an actual champion of gay civil rights. Ultimately, Hartmann got the measure passed by the APA assembly and sent on to the board for the pivotal, and successful, December 1973 vote.

At that time, the APA also put its weight behind civil rights protections for gay people and supported the repeal of state sodomy laws then on the books in 42 states and Washington, D.C. (When the Supreme Court finally struck down all such statutes in 2003, 14 states still had them.)

“With various populations, it was taken as a sign of a reasonable scientific health that a large organization could be open to real discussion and real rethinking,” said Hartmann, who gradually came out as gay over the next two decades and served as president of the APA from 1991 to 1992.

The sea change

Asked about his own reaction 50 years ago to this sea change in the APA, Hartman said, “We at the time didn’t know what it would mean. It turned out to be very influential.”

That’s putting it mildly. The full parade of barriers to gay civil rights — including housing and employment discrimination, laws governing sex between consenting adults, and the bans on gay people immigrating, adopting children and marrying — all hinged on whether gay people were defined as constitutionally well or as psychologically sick, clinical pariahs at a time when all manner of psychiatric disorders were magnets for stigma and discrimination. And so, the APA’s policy change sent off shockwaves that continue to course across the legal landscape.

The APA did not, however, make a clean break from pathologizing homosexuality with the 1973 board vote. As a compromise in the face of resistance, the leadership allowed for a new diagnosis to enter the DSM at that time: “sexual orientation disturbance,” for people who were distressed over their homosexuality, including those who wished to change it. This diagnosis was then replaced by “ego-dystonic homosexuality” in 1980. That diagnosis was struck in 1986; but at that time, the symptom of “marked distress about one’s sexual orientation” was newly included in the diagnosis of “sexual disorders not otherwise specified.” That last vestige of pathologized homosexuality wouldn’t finally be deleted until 2013.

Critics say those various diagnoses helped legitimize decades of conversion therapy efforts. Research that began to emerge in the mid-1990s ultimately discredited this practice, which although still carried out, is now widely condemned as harmful and ineffective by mainstream mental health professionals and is banned for minors in 22 states and Washington, D.C.

The new frontier

Kunzel is among those who look at homosexuality’s decades-long evolution in the DSM and see at least a partial parallel to the more recent effort to depathologize transgender identities.

“Transsexualism” first entered the manual in 1980, enraging many trans activists for, they argued, turning their identity into a sickness. This was replaced in 1994 by “gender identity disorder” — an effort by the APA to mitigate stigma that nevertheless left many trans people unappeased. Then, in 2013, that diagnosis was replaced by the current “gender dysphoria,” which distances the source of distress from the core sense of self and attributes it more to society’s stigma toward gender nonconformity.

Today, there is sustained pressure on the APA to discard the gender dysphoria diagnosis and, just as with gay and lesbian people, totally depathologize trans people in the eyes of psychiatry. However, because receiving hormones and transition-related surgeries is key for many trans people to fully realize their identities, and given that insurance companies require a diagnosis to cover such treatment, tension remains that may prove irreconcilable.

Levounis, the current APA president, declined to take a position on what should become of the gender dysphoria diagnosis.

“It’s a very active debate within our field,” Levounis said. “Unlike other discussions within the APA of yesteryear, we do involve a lot of lived experience in our work — people who are transgender,” including psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists alike, “who do help inform us in these discussions.”

Hartmann said the effort to depathologize homosexuality has “a mixed relevance to the present, very lively and argumentative field” of gender identity — one in which he hopes to see further research that will yield clearer insights.

Surveying the fruits of his own efforts five decades ago to strike homosexuality from the DSM, Hartmann said, “I think it has helped an enormous number of people’s self-esteem. I think it has helped them face real problems in their life, including psychiatric problems. I think it has helped them fight for justice in other realms. And I think some people came around and became thoughtful about what other things are unfair.”

Comments