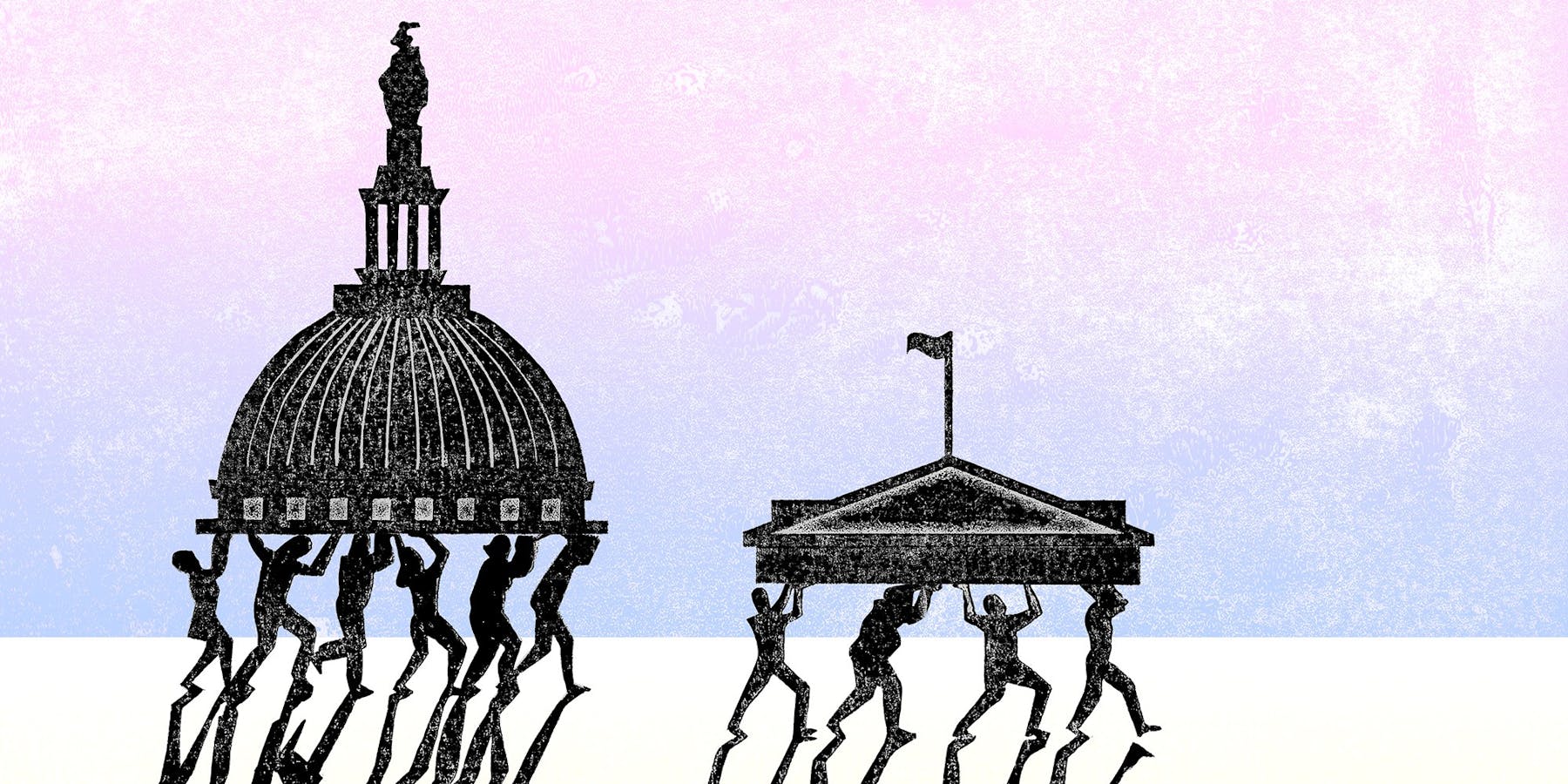

What if Donald Won’t Concede

President Trump is strongly signaling that if he loses the 2020 election, he won’t accept the results. That could lead to a crisis. The election will likely bring slow vote counts in key battleground states and high numbers of expected contested mail ballots. Recent protests have already turned violent. And the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg means any crucial court decisions will land in a Supreme Court that's short one member or packed with Trump appointees.

If the election is close and contested, it could test American democracy more than any race in a century.

Trump has spent months attacking the integrity of the election and lying about mail voting. And he’s setting up a scenario to claim he’s won on Election Day, before those Democratic-leaning votes are counted.

“The only way we’re going to lose this election is if the election is rigged,” he declared at a rally last month.

He escalated that rhetoric even further this week. On Thursday, Trump tweeted that the election’s “result may never be accurately determined, which is what some want.”

“What’s going to happen on November 3rd when somebody’s leading, and they say ‘well we haven’t counted the ballots, we have millions of ballots to count.’ It’s a disaster,” he said Friday. “This is going to be the scam of all time.”

Trump has lied about voter fraud in the past as well, insisting even after he won in 2016 that he would have also won the popular vote if millions of votes hadn’t been cast illegally — an outright falsehood — while casting doubt on some 2018 midterm results. The truth is that voting fraud is exceedingly rare, and widespread voting fraud of the kind that can sway an election is even rarer.

Trump’s rhetoric sets up a possibility that he will refuse to accept a loss. And long vote counts and potential fights over rejected mail ballots in the states most likely to decide the election — Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — increase the chance of chaos. Since Democrats are more likely to vote by mail, Election Day results may look good for Trump before late-breaking ballots cut against him.

And mail ballots are a lot more likely than in-person votes to get rejected by election officials, which could lead to court fights over whether they should be counted.

Multiple groups have been preparing for — and warning about — what might happen come November.

The National Task Force on Election Crises, a new group formed by a bipartisan coalition of senior former government officials, scholars and voting rights leaders to try to protect democracy in the event of a contested election, held a Thursday summit to brief reporters on ways to combat disinformation before and after the election.

The Transition Integrity Project, a separate group of senior political strategists formed to prepare for the election, war-gamed different election outcomes earlier this summer. The terrifying results they produced led them to conclude that unless Biden wins a blowout, “the potential for violent conflict is high.”

‘A nightmare in terms of the health of the nation’

First, let’s dispel some more paranoid scenarios: Trump has no power to unilaterally hold onto power or cancel the election. Even if he holes up in the White House, his current term will end on Jan. 20.

But a number of crucial battleground states will likely take days or even weeks to tally up their votes because of the major spike in mail voting expected due to the coronavirus. That will prove stressful and could lead to conspiratorial charges from whoever’s losing. That won’t be pretty, but it isn’t a full-blown crisis — that’s just the consequence of the onerous process of counting a lot of mail ballots, which many states are doing for the first time this year.

Court fights over ballots also happen in nearly every political cycle, and state court battles are almost guaranteed if this is a close race.

But a lengthy, nasty and partisan court fight with the White House on the line, like the 2000 recount between George W. Bush and Al Gore, would be especially fraught given the current political atmosphere.

The real problem comes if a partisan state supreme court — say, Wisconsin’s GOP-allied majority, or Pennsylvania’s Democratic court — twists the law to find a favorable ruling for their side that could decide the election that then gets appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Friday means if her seat isn’t filled before Election Day, any fight that goes that far would be decided by a court that could deadlock four to four on a key decision. If Republicans ram through a replacement, giving them a six to three ideological edge, an unfavorable decision from the court may not be accepted by Democrats.

“We have plenty of cases of both parties behaving exceedingly badly, and unfortunately we have plenty of cases of state courts letting them get away with it if they’re controlled by allies,” warned Case Western Reserve University Professor Jonathan Adler.

“The biggest lesson of 2000 is that our election systems are not sufficiently robust and reliable to handle results that are within the margin of error, and if anything that’s only become more true since then. Any election that’s within the margin of error is going to be a nightmare in terms of the health of the nation.”

|

| (Intercept) |

A real risk of violence

America has already seen isolated bursts of political and racial violence in recent years. The white supremacist massacres in Charleston, El Paso, and Pittsburgh have given way to more recent politically fueled killings by a right-wing extremist in Kenosha and a left-wing extremist in Portland in the past few weeks.

And partisans on both sides are primed to expect a rigged election: According to a recent Yahoo News/YouGov poll, only 22% of Americans believe the election will be “free and fair.”

In a highly charged atmosphere, if the president claims the election is being stolen from him that could trigger more violence, even if his claim isn’t plausible. That likelihood only increases if the election comes down to heated legal fights, with accompanying protests and counter-protests. Conversely, if liberals think Trump is using the courts to steal the election, especially if he moves to suppress protests or stir violence with overheated rhetoric, things could get ugly.

“There will be crazies on both sides who will be willing to go to the streets and seek violence. We’re seeing that now in places,” said Peter Feaver, a Duke University professor and former member of the National Security Council under George W. Bush. “It’s not crazy to believe the risk of that will increase, particularly if uncertainty about the outcome extends for weeks. That would be a lot of social strain.”

During a Thursday summit by the National Task Force on Election Crises, former Department of Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, a Republican, warned about what might happen immediately after the election — even as he warned that it shouldn’t be the place of his old department to get involved in any post-election unrest.

“I do worry a little bit about violence from extremists on both sides and I hope that the states and cities have got plans to deal with this issue with their own law enforcement authorities, security authorities, but doing so in a way that does not intimidate voters,” Chertoff said.

And that’s not even the worst-case scenario.

Things get much scarier in a close election

There’s a big difference between Trump getting walloped and whining about a “rigged” election as he leaves office, him losing by a close margin and fighting things out in the courts before eventually accepting the results, and a genuine nail-biter that could lead to an actual constitutional crisis.

If the current political climate holds and public and private polls are right, Biden will likely win the election — once all ballots are counted.

Biden currently has consistent leads in the polls in enough states to put him over the top in the Electoral College, even if all the states that are pure tossups right now break against him. If that happens, it matters less if Trump claims the election was stolen from him. If he’s tweeting from Mar-a-Lago after leaving the White House or he’s simply sour-grapes tweeting to spin away his loss that’s not much of an existential threat.

That doesn’t mean things will go smoothly — but Trump will only have limited power to wreak havoc if he’s getting thumped.

But even a relatively comfortable Biden win could take days or weeks to sort out. The four states that are most likely to decide the election — Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — also happen to be states that this year allow mail voting, all of them but Arizona for the first time during a presidential election.

That could lead to a long count with a ticking clock: Under federal law, states must certify their election results by December 8. Pennsylvania took nearly three weeks to complete counting all its ballots after its June primary, and turnout for that race was only about one third what officials are expecting in November. That doesn’t leave much wiggle room for legal challenges and court fights.

Trump is likely to have a big lead in some swing states on election night even in states where he’s lost — what Democratic data firm Hawkfish recently warned would be a “Red Mirage.” Polls show that Democrats are going to vote by mail at much higher numbers than Republicans this election, partly because of Trump’s attack on mail voting. A recent Marquette University poll of Wisconsin showed that 47% of Democrats plan to vote by mail, while just 18% of Republicans do. Wisconsin, like Michigan and Pennsylvania, can’t start preparing mail ballots to be counted until Election Day, so most Democratic ballots won’t be counted that night.

Trump could have what looks like a huge lead at that point, only to see it erased in the coming days and weeks. On top of that, mail ballots are more likely to be initially rejected or provisional and subject litigation from both sides over whether they should count, because of questions about issues like whether a voter’s signature matches the one on file, or in Pennsylvania, rejections because a voter forgot to put their ballot in a secrecy envelope before putting it in an outer envelope to mail it back.

Both parties have already lawyered up in a huge way, and the lead-up to the 2020 election has seen more election-related litigation than in any recent year as Democrats sought to loosen voting restrictions due to the coronavirus pandemic and Republicans fought to limit mail voting.

It appears that Trump’s attorney general is ready to follow his lead in the case of litigation and further politicize the Justice Department in Trump’s service. In just the past ten days, Bill Barr intervened to thwart a defamation lawsuit Trump is facing from a woman who said he raped her, attacked his own career staff for bucking his actions, and reportedly encouraged local officials to charge protestors with sedition. And he recently refused to promise that the DOJ wouldn’t get involved in the election’s aftermath.

And top Democrats have signaled that they won’t give an inch in a close race.

“Joe Biden should not concede under any circumstances because I think this is going to drag out, and eventually I do believe he will win if we don't give an inch and if we are as focused and relentless as the other side is,” Hillary Clinton recently said.

Potential for an actual constitutional crisis

If Trump claims millions of ballots are fraudulent and seeks to stop them from counting, he doesn’t have much of a legal argument. But how state GOP officials react to his rhetoric could matter a lot.

Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin all have Democratic governors and Republican legislatures, and the decision for how to cast electoral college votes rests with the legislature.

It’s unlikely but not totally clear legally what would happen if a legislature decides in one of those states to reject the election results and name Trump the state’s winner if a close count goes against him but he claims fraud. In response, those states’ Democratic governors could declare that Biden won. That would be a real constitutional crisis, with two competing slates of electors.

“Things would get problematic if the legislature tries to take back the power to choose electors by claiming the popular vote failed,” Ned Foley, an Ohio State University professor and member of the National Task Force on Election Crises, told VICE News.

“If count in swing states becomes mired in litigation, confusion and delays, it’s possible the states won’t resolve their election by the December 8 deadline,” warned Amherst University Professor Lawrence Douglas, who wrote a book on possible election nightmare scenarios. “It’s hard to map out a peaceful and harmonious exit strategy from that situation given the fact that we have an occupant of the White House who’s willing to play constitutional brinksmanship.”

Republican state lawmakers have already been playing politics with the election in all three states. Legislators in all Wisconsin and Michigan rejected requests from their secretaries of state to be allowed to begin counting ballots. In Pennsylvania, Republicans have refused to do so unless Democrats agree to make major changes to restrict mail voting, a non-starter.

If a state submits two competing slates of electors, the decision would then get kicked to Congress, where a bicameral vote would be held presided over by Vice President MIke Pence. If Democrats still hold the House and Republicans still hold the Senate, the most likely scenario in a tight presidential election, it’s unlikely they’d be able to land on a consensus on who won the presidency. And constitutional scholars hold widely divergent views on what rules would govern such a congressional fight.

The last time the country went through a situation like that was the disastrous 1876 election. Multiple states sent competing electoral college delegations, a divided Congress failed to agree on which was valid — a months-long constitutional crisis only ended by a last-minute deal that made Republican Rutherford B. Hayes president in exchange for his agreement to end Reconstruction and return the South to white supremacy.

Congress passed an act in that election’s wake to try to avert a similar future election, the Electoral Count Act of 1887. But experts say the law is convoluted at best — Douglas called it “incoherent” — and it doesn’t address some basic issues, like whether the Electoral College count drops from 270 if a state’s electors are rejected. The law has never been tested in court. The Supreme Court could be forced to intervene to settle different interpretations of the law — a huge problem given the vacancy created by Ginsburg’s death.

Comments