Gay Lives Are Finally Being Discovered. {{Pride Month 🌈 }}

|

| (Image credit: 5 Continents Editions) |

Earlier this year, the TV miniseries It's a Sin rightly won acclaim for its depiction of the Aids crisis in the UK during the 1980s and 1990s. But when I heard people raving about the show, written by Russell T Davies, I was struck by how many of them admitted to knowing little about the epidemic – and the destruction it wreaked among the gay community.

– Were these men Leonardo da Vinci's lovers?

That’s because, even in today's much more accepting society, the history of the gay and lesbian community is largely a forgotten history. For a long time, the mainstream public didn't want to hear our stories.

"I would venture to say that the public were disgusted and outraged," says author Crystal Jeans. She points to the response to the watershed lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall in the 1920s as just one famous example of the way authors have caused hysteria simply by acknowledging queer lives. Despite the book containing just two very mildly suggestive sexual references, "everyone went berserk and it was banned", she says.

Filling the gaps in is my speciality – Patrick Gale

This is what inspired me to write my latest novel, The Secret Life of Albert Entwistle. It's about a lonely, socially awkward and secretly gay postman living in a fictional town in the north of England who hits retirement, realising he wants to turn his life around and finally be happy – but to do this, he needs to find the love of his life, a man he hasn’t seen for nearly 50 years. His search for his lost love is interspersed with a series of flashbacks to his youth that gradually reveal the pressures their relationship found itself under as a result of the social climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s – and ultimately how these pressures tore them apart.

I'm not the only writer who's introducing queer history to a popular audience. My novel is riding on a wave of interest that dates back in the UK to 2017 and the 50th anniversary of the beginning of decriminalisation of homosexuality. That same year, the so-called "Alan Turing law" offered pardons to 49,000 British gay men who’d been convicted of homosexual acts – following a campaign arguably bolstered by the greater awareness brought about by The Imitation Game, the hit film that depicted the conviction and chemical castration of the Enigma-codebreaking computer scientist.

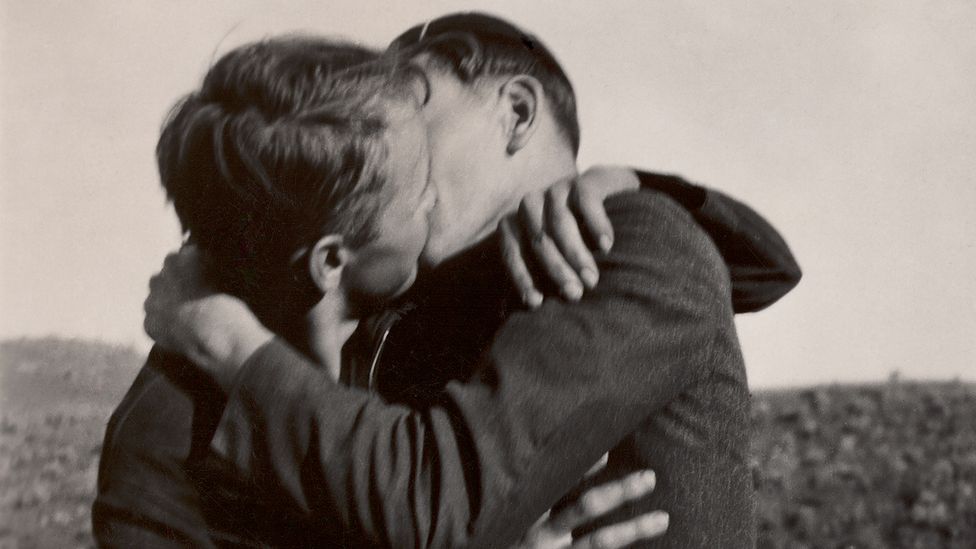

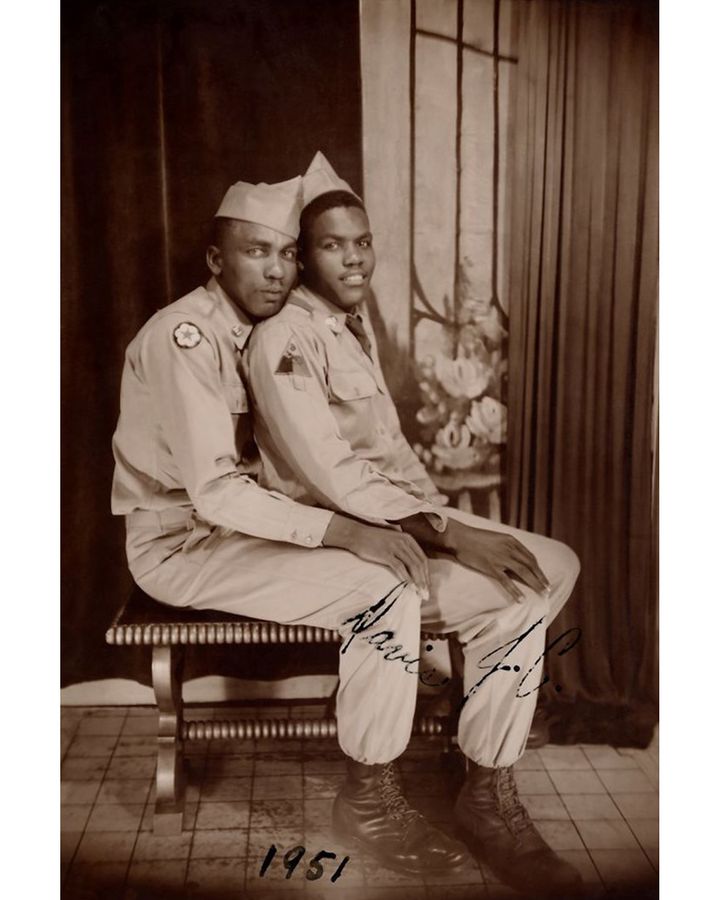

The increased interest in queer history is by no means limited to the UK. Loving by Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell is a book of photos from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries (found in flea markets and car boot sales) that show men who appear to be in love. It was launched in the US and internationally in October 2020 – and is already entering its fifth print-run. Over on Instagram, The Aids Memorial shares photos and stories of people – predominantly gay men – who died of the disease, written by those who loved them. It now has 185,000 followers. Meanwhile, on Netflix, 2020 documentary A Secret Love tells the story of a US lesbian couple who kept their relationship secret from their families for nearly seven decades.

Most original queer source material was written by privileged people. You’d not catch many queer coal miners jotting down their memoirs – Crystal Jeans

However, it's fiction that’s very much driving the phenomenon of bringing "lost" stories of gay life from the past to light. Over the last five years, a trio of Irish writers have delivered stunning gay-themed novels set predominantly in periods of history that didn't welcome them – John Boyne (The Heart’s Invisible Furies), Graham Norton (Home Stretch), and Sebastian Barry (the Costa Award-winning Days Without End). In the theatre, Matthew Lopez's exploration of gay male history The Inheritance triumphed in London before transferring to New York, where it opened the year after a well-received revival of Mart Crowley's seminal 1968 play Boys in the Band. Last year, the latter was remade as a film for Netflix by Ryan Murphy.

Indeed, Murphy has led the way with fictionalising queer history for a popular TV audience: having finished its third and final season last week, Pose blew open the drag ball culture scene of New York in the late 80s, and last year's Hollywood was a LGBTQ+-themed fantasy set in 1940s Los Angeles. Elsewhere on the small screen, It’s a Sin's five episodes have had a total of over 18 million views in the UK, while it earned near-universal raves on both sides of the Atlantic. Add to this recent queer-themed period films Carol and Call Me By Your Name, plus the French indie hit 120 Beats Per Minute, a love story set amongst the Aids activist movement of 1980s Paris, and it is clear that there is now a huge scope for telling queer stories in mainstream film and TV. Most recently, the internet exploded with behind-the-scenes photos of Harry Styles from the shoot of new film My Policeman, an adaptation of Bethan Roberts's 2012 novel starring the pop superstar as a closeted gay man in the 1950s.

Why fiction is leading the way

As a novelist, it interests me that fiction is at the forefront of this dissemination of queer history. This may be because any historians wanting to write about real-life characters are faced with a very serious problem. Most queer people from the past went to great lengths to conceal their identity – sometimes marrying and starting families, at the very least destroying all evidence. After their deaths, if families found letters, diaries or photos, they usually destroyed them (which explains why those photos featured in the picture book Loving come with no caption or explanation). This has made it all too easy for historians to erase our existence from the record and deny the contribution we’ve made to society.

Even when evidence does exist of same-sex relations – as is the case with 19th-Century Yorkshire landowner Anne Lister, the subject of BBC/HBO series Gentleman Jack, or Queen Anne, subject of Oscar-winning film The Favourite – this is often coded, covert or patchy. We have to rely on fiction to fill in the gaps.

"Filling the gaps in is my speciality," says British writer Patrick Gale, whose 2017 BBC TV drama Man in An Orange Shirt explored the fallout of same-sex desire echoing through three generations of one family. "In fact, I’m only drawn to fictionalising true-life material where there are gaps in what can be known or proved." Gale's 2015 novel A Place Called Winter saw him draw inspiration from the story of his great grandfather Harry, who left his family and emigrated to Canada in the early 20th Century. However, as a way of explaining the mystery surrounding why Harry left behind everything he knew, Gale imagined a situation in which he was forced to leave as a result of a gay affair being exposed. "[His story] had these echoing spaces in it which I could join by using my imagination and wondering how I’d have behaved in his position."

History empowers us. At its most fundamental, it says, 'We have always been here. We have a place' – Stephen Hornby

Gale is taking similar imaginative leaps with his next novel, which is about the British poet Charles Causley. "He was quite clearly queer – to judge from his private letters and diaries – and yet not remotely ready to be comfortable with admitting that, even to himself," he explains. "We know he was in the Navy and that he wrote poems which suggest his war experiences carried a powerful emotional charge; we know that he kept until his dying day a letter from a fellow officer with whom he seems to have had some kind of relationship. So what fiction can do, which a straightforward biography cannot, is to solve those mysteries in an emotional nourishing way. It doesn’t matter if it wasn’t true because it would have been true for other men in a similar situation."

The challenges in recounting the past

The challenges in recounting the past

Crystal Jeans's latest novel is The Inverts, which tells the story of two best friends – one a lesbian, the other a gay man – who enter into a fake marriage in the 1920s. She believes that queer history offers writers a rich territory to mine but points out the constraints of working from real-life testimonies. "From what I’ve noticed our pool to fish from is a bit limited. Most original source material – diaries, books etc – was written by privileged people. White and wealthy. You’d not catch many queer coal miners jotting down their stream-of-consciousness memoirs between shifts. Vita Sackville West left us her letters.

Gladys Bentley did not."

This was another reason I wrote The Secret Life of Albert Entwistle; I wanted to tell the story of one ordinary young gay man trying to express his love for another at a time when this would not have been accepted. But I also wanted to contrast this disturbing, sometimes horrifying picture with what life can be like for a gay man within today’s much more accepting society in the UK – and celebrate how much progress we’ve made. My inspiration was a series of interviews I conducted with older gay men whilst I was Editor-in-Chief of Attitude magazine, as part of our celebration of the 50th anniversary of the start of decriminalisation. I was stunned by the emotional impact and intensity of these stories of relentless persecution and oppression, of lives dogged by fear and shame. And I wanted to make sure stories like these weren’t lost – and reached as large an audience as possible.

When it comes to written – rather than verbal – evidence of working-class queer lives, this is often ambiguous. For Stephen Hornby's last play, The Adhesion of Love, he researched a group of working-class men from Bolton who set up a Walt Whitman appreciation society in the 1880s. They entered into regular correspondence with America’s great queer poet – and two of them even travelled to New York to visit him. In the play, Hornby has inferred that the men were what we'd now call gay. "If we look at the record that does exist of the Bolton men’s lives with the assumption that they were heterosexual," he says, "we're just left with a lot of puzzles and unanswerable questions. If we flip it, and assume they were interested in men sexually and emotionally, then all those puzzles disappear, and all the questions are answered."

|

| Pop star Harry Styles is starring in new film My Policeman as a closeted gay officer in the 1950s (Credit: Getty Images) |

But Hornby is careful to point out that before writing any play he carries out extensive research. "I've been working with the primary archival materials for weeks. I’ve read the contextual histories of sexuality in the period. I've visited the sites of the events. And then, crucially, I've made a homonormative assumption and told my story from that position."

As a fellow patron of the UK's LGBT History Month, creating an authentic fictional history is a responsibility I took equally seriously when writing The Secret Life of Albert Entwistle. I carried out extensive historical research into the context of the period I was exploring and returned to the interviews I conducted while at Attitude. I wanted to do justice to the men who'd lived through similar experiences but didn't survive or weren't able to make their stories heard. And while my hope is that I've created a story which straight people will find interesting, I'm aware that, for the LGBTQ+ community, the stakes are much higher.

"What we see all through history is that people are denied their past as part of a way to control them," says Hornby. "The fascist playbook is always to destroy the history and culture of the minority it is repressing. History empowers us. At its most fundamental, it says, 'We have always been here. We have a place.'"

For the LGBTQ+ community, telling our stories and knowing our history is a matter of both self-discovery and survival.

NOTES OF SURVIVAL FOR THIS BLOG. DO YOU THINK AFTER 14 IT SHOULD BE ENOUGHT OR KEEP ON GOING? Please read

Comments