How Do You Come Out When “Gay” is Not The Way You Talk

When 13-year-old Tien wants to tell his mother he’s gay, he goes to the library. But he quickly realises there aren’t any appropriate words for homosexuality in Vietnamese. He eventually finds a mix of words in his native language and English to confide in his mother, who is not very conversant in English.

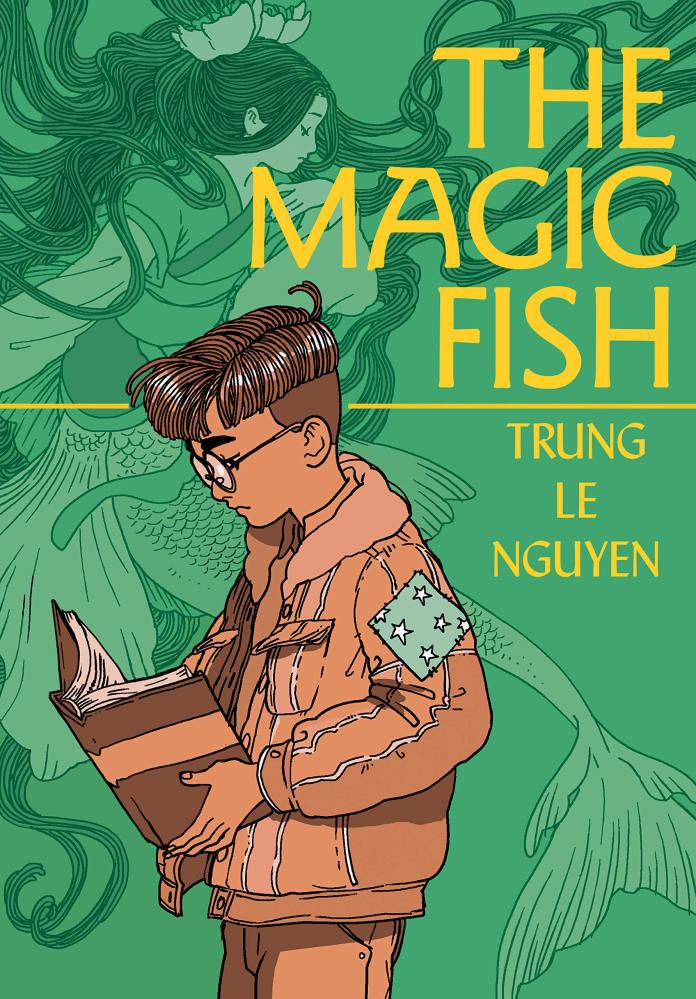

Tien is the protagonist of The Magic Fish, a graphic novel for young adults by Vietnamese-American writer Trung Le Nguyen, published in October last year. Inspired by Nguyen’s own story, it draws on his struggle to find the right words to express same-sex attraction and non-binary identities in the absence of such vocabulary in his mother tongue.

Unfortunately, this is a quandary faced by a large number of people in the LGBT community: access to relevant information, a great deal of which is online but only in English.

For millions across Asia, it is a monumental problem. The less widely spoken the language, the smaller the number of reliable sources of useful information. On December 1 last year – World Aids Day – a Singapore-based company sought to address this lack with asia.gay, the region’s first community-led platform designed to provide the latest news on gay health, lifestyle and a host of other topics in a number of Asian languages, and in English.

Pages in Thai, Indonesian and English are now available on the site, and moderators plan to add an average of one language a month this year. Next up are Burmese, Malay and Arabic. Asia.gay was also the first site to use the top-level domain name .gay after it was made available to the general public last September.

“A few months ago, my partner in Thailand and myself, through the separation lockdown, started looking at gay websites, gay travel apps, et cetera,” says Gerard Clancy, director of Singapore-based M+B Private, which owns the site. A 57-year-old Australian who has lived in Asia for more than 30 years, Clancy saw the massive language gap. “Most of the websites were available only in English, apart from Chinese,” he explains.

Although there is a wide range of resources available to the gay Chinese community, even those fall short in the larger context. “There is plenty of information about sexual health, especially [sexually transmitted diseases], for gay men in Mandarin. However, there is not much information about LGBTI+’s sexual health and other issues,” says Sean Sih-Cheng Du, director of policy advocacy at the Taipei-based Taiwan Tongzhi (LGBTQ+) Hotline Association.

Set up in 1998, the hotline is the oldest and largest resource in Taiwan, serving more than 50,000 people each year. It is accessed mainly by those in the region and from other Mandarin-speaking areas including Singapore, and also Malaysia.

For the asia.gay team, such harsh realities helped solidify their plan. The team members wanted to provide useful information from trusted sources in a digestible form and in non-medical terms in a range of local languages.

“We try to couch medical information in stories that are entertaining and fun so they can get access to information not just from a medical perspective, but also how they live their lives,” says asia.gay’s editor, Yen Feng, a 41-year-old Singaporean.

*************

Inspired by author Trung Le Nguyen’s own story, The Magic Fish draws on his struggle to find the right words to express same-sex attraction.

As a first step in the search for a reliable source the team found the Bangkok-based Pulse Clinic, a gay-owned private entity that promotes and provides care and education in sexual well-being, HIV and related infections, with over 45,000 clients in 130 countries.

“We’re not here to campaign for political reform,” Feng says. “We’re not trying to make governments accept homosexuality. What we’re trying to do is just to improve access to important health information for Asia’s gay community.”

From an editorial perspective, Feng is alert to potential hassles in terms of safety for both contributors and readers. Writers who are wary are identified with pseudonyms and illustrations. On the other hand, if a contributor feels it’s an important cause and wants to stand up for it, that is encouraged.

Asia is so huge and what we’re trying to do is so big. We are going to fall short on some things

Yen Feng, asia.gay’s editor

Since Asia is far from homogenous, cultural differences, religious beliefs and language nuances also have to be considered. “Take Arabic, for instance,” Clancy says. “We certainly have the capacity to do the translations, but the cultural and religious nuances have meant that we have held off because we want to do a little bit more research, talk anecdotally to various groups, so that we are sensitive to the people and region. We want to make sure we are as right as we can be, that the content is relevant and appropriate for that language group.”

The most logical route has been the community itself, Feng says. “For Bahasa Indonesia for example, I sent the translations to my contacts throughout Indonesia and asked what they thought,” he explains. “They responded with things like, ‘Oh, in this part of Indonesia, we don’t mean to say it this way,’ or ‘We refer to people with HIV this way.’ So there are going to be discrepancies and we cannot account for all the differences.”

The team has devised a framework that seems to work. “My question was: ‘Do you understand what we say?’” Feng says. “The general consensus was ‘yes’. So I think that’s one of the checks that we have for ourselves, which is to make sure that the local, native community finds our content understandable.”

Though Feng and Clancy will not share specific traffic numbers, they say the figure is “healthy”, and they are heartened that the site is accessed as far away as the United States. Feedback has been encouraging and enthusiast.

The asia.gay site is vibrant, eye-catching and diverse. As well as providing information about gay men’s health and HIV, it offers entertainment news, film, music and book reviews, articles about relationships, and advice.

The team is mindful that there will be difficult issues to navigate, whether with the local government or being blocked in some jurisdictions, and some people will not be supportive.

“We talked through it and asked ourselves if we should do anything preventative on that front,” says Clancy. “We decided not to at the moment.”

Both men are conscious of the enormous task they have taken on. “Asia is so huge and what we’re trying to do is so big. We are going to fall short on some things,” Feng says. “But I think one of the biggest reasons why we want to continue to do this is to make sure that we are in sync, and to be kind of the bellwether for what’s happening in the various communities.”

Comments