This Angel Doctor is Responsible For Lowering HIV Rates/Deaths in NYC, Young and Gay He Was in The Middle of It

On a brisk November afternoon at Mount Sinai Comprehensive Care Clinic in Manhattan, Dr. Demetre Daskalakis sat in a brightly lit exam room, clicking away on a keyboard as his next patient walked in. The patient was in his 50s, and his first question was about his mental health. He felt depressed, but he didn’t know why. The patient recently stopped smoking and drinking, and an abdominal pain had him worried. He said his libido was nonexistent, even though he had a regular partner.

“How much of it do you think is because of your brain, and how much of it is because of your penis?” Daskalakis asked. He peppered his patient with questions about the nature of his erectile dysfunction.

Eventually, Daskalakis discussed the patient’s HIV viral load and CD4 count, markers of the progress of his HIV infection. The patient’s blood tests indicated his viral load remains undetectable — meaning the amount of HIV in his blood is so low, thanks to HIV medications, that he can’t transmit the virus sexually.

Daskalakis, 45, updated his patient’s cholesterol medication and wrote him prescriptions for six Viagra tablets and a flu shot. He gave the man a hug goodbye and, before he walked out, said “Text me.”

Daskalakis still sees patients, as he has since the late 1990s, but today he’s just moonlighting as a clinician. The infectious disease specialist squeezes his patients in around the busy schedule of his main job: deputy commissioner for the Division of Disease Control at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, one of the world’s largest public health agencies.

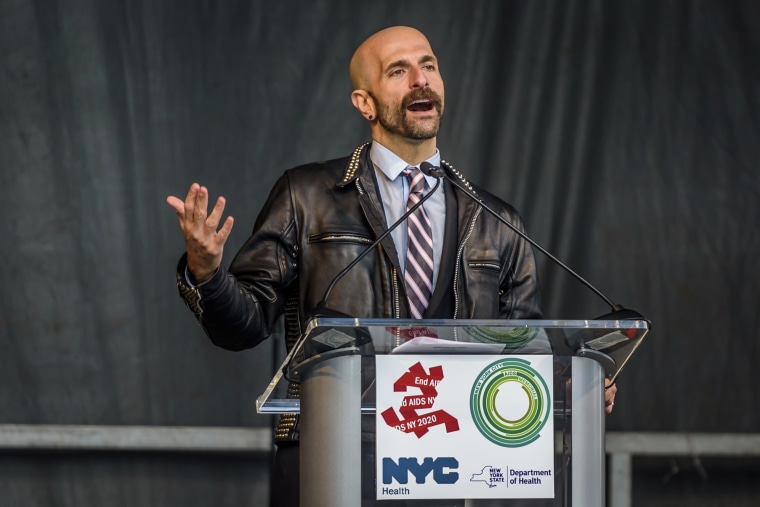

Demetre Daskalakis speaks at the formal dedication ceremony of New York City AIDS Memorial Park at St. Vincent's Triangle on Dec. 1, 2016.Erik McGregor / Sipa USA via AP

Since joining the city’s health department in 2013, Daskalakis has promoted a framework for treatment and prevention strategy that he calls “status-neutral care,” which uses the same approach to initial patient care regardless of one’s HIV status. This type of care is intended to reduce HIV stigma and encourage frank discussions about sexual health, HIV risk and prevention options.

Today, the results of “status-neutral care” are beginning to be seen in public health data. On Thursday, the city released its annual raw data on diagnoses, which showed a record low 2,157 new HIV diagnoses in 2017, a 5.4 percent drop from 2016. The decline is most dramatic among men who have sex with men, whose rate of new infections is estimated to be 35 percent lower than 2013.

‘RADICAL GAY DOCTOR’

Before entering the municipal public health world, Daskalakis earned a reputation as “a progressive, radical gay doctor,” according to Mark Harrington, the executive director of Treatment Action Group, an HIV/AIDS organization.

During a 2012-2013 meningitis outbreak in New York City, Daskalakis went straight to those most at risk — including men who have sex with men, patrons of commercial sex venues and weekenders in Fire Island — and set up a popup vaccine clinic, occasionally dressed in drag as a nurse to take the edge off the injection. The effort was so successful that by August 2013, the outbreak was contained, and officials credited this aggressive vaccination campaign with halting it, according to The New York Times. Shortly after the meningitis campaign, a position opened at the NYC Department of Health for assistant commissioner of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control. Daskalakis said his “email sort of exploded with people saying, ‘Hey, you should apply for this.’” He threw his hat in the ring and was offered the job, and as he was deciding whether to accept the offer, he said his mind was made up after he received an email from Mark Harrington, saying, “History’s calling. Are you going to answer?”

Harrington recalled telling Daskalakis, “This kind of opportunity won’t come around again, and you’ve got a new [mayoral] administration, you’ve got a governor committed to ending the AIDS epidemic.”

Daskalakis said this made him realized the job offer came at an “opportune moment in the history of HIV in New York City.”

“There was an effort that was motivated by the community to look at New York City and New York State as a place where we could prove that we could end an epidemic of HIV,” he explained.

NEW WAVE OF ACTIVISM

Around 2012, Harrington said it became clear that “we had the tools to bring down the rate of new HIV infections so drastically that it was possible — even without a cure or vaccine — that we could essentially end the epidemic in places where there was access to high-quality treatment and prevention.”

Part of the reason it was possible, he added, was the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, which meant more young people and poor people were eligible for health insurance than ever before.

The way to end the HIV epidemic without a cure or a vaccine, according to Harrington, is by scaling up the use of two novel prevention tools: PrEP and TasP.

PrEP means “pre-exposure prophylaxis,” and it involves taking a daily Truvada pill to prevent HIV infection. Studies proving PrEP works were published in 2011. Since then, the government has recommended that more and more people consider the drug. This November, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that doctors assess all Americans’ HIV risk, and counsel patients to take PrEP if they are at risk, including women who recently had any sexually transmitted infection, vastly increasing the number of people recommended to take the drug.

TasP means “treatment as prevention” and is a moniker given to the realization that HIV positive people can’t transmit the virus through sex if they are undetectable. Until 2015, treatment guidelines had HIV patients wait until their immune systems began to weaken before starting medication. Studies proving that starting treatment early helps HIV patients and also blocks transmission were published between 2008 and 2015.

“We were treating people late, and in many cases too late, to block transmission,” Harrington explained. When studies were published proving PrEP and TasP were both safe and beneficial, health bodies around the world overhauled their HIV guidelines and recommended that many millions more people begin taking antiretroviral drugs in order to control the HIV epidemic.

Harrington said this realization drove a “new wave of activism” at the 2012 International AIDS Conference in Washington, D.C. Activists began to talk about an idea that had been abandoned after the failure of HIV vaccine and cure trials: ending the epidemic.

In 2014, soon after Daskalakis joined the NYC Department of Health, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced the formation of “Ending the Epidemic,” a task force that would be responsible for devising a plan to use these new tools to draw down the state’s historically high HIV incidence. Daskalakis sat on the panel and was instrumental in developing the state’s robust PrEP program.

‘ENDING THE EPIDEMIC’

“The definition of ending HIV is a mathematical one,” Daskalakis explained. If New York City could get new infections down below 750 a year by 2020, he said new "transmission would no longer be fueling the epidemic."

When Daskalakis started work at the NYC Department of Health, he did so at a moment when it was suddenly possible, with proper inputs of political will and cold hard cash, to use antiretroviral drugs to engineer an end to HIV transmission in the city. The political will of Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo, he explained, helped secure the funding needed to scale up the distribution of expensive medications like Truvada.

Some of the language in this new HIV/AIDS prevention paradigm was coined by Daskalakis himself: “status-neutral care.” In an article in Open Forum Infectious Diseases, a medical publication, Daskalakis described status-neutral care as a “multidirectional continuum [that] begins with an HIV test and offers 2 divergent paths depending on the results; these paths end at a common final state,” which is the prevention of HIV transmission.

Daskalakis overhauled the city’s sexual health programs to make them status-neutral. STD clinics were renovated, streamlined and rebranded as “sexual health clinics.”

“All the services had to look alike, whether you're HIV-positive or negative, and the idea was that if you come in and you are newly diagnosed with HIV you get started on meds on the same day of your diagnosis,” he explained. “If you are at risk for HIV, and you test HIV-negative, we don't dilly dally and wait. We start you PrEP that same day.”

Ad campaigns that had attempted to shame people out of contracting HIV instead distilled prevention down to a simple formula: “New boo? Get tested!” That’s because in the status-neutral-care continuum, getting tested is the first step to getting a patient enrolled in PrEP or TasP.

An advertisement from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.NYC Dept. of Health and Mental Hygiene / NYC DOHMH

Gone were the scare-tactic campaigns of the Bloomberg administration (one infamous YouTube ad showed a close up view of anal cancer). They were replaced by joyful, brightly colored ads that encouraged people to come in for STD testing. Joining those ads were public awareness campaigns aimed at underserved communities with higher-than-average HIV incidence, like Spanish speakers, transgender women and heterosexual women of color. For the past several years, New York City subways and buses have been plastered with health department PrEP ads.

'REAPING THE BENEFITS'

The success of New York City’s revolutionary HIV prevention program is seen in the city’s declining rate of new HIV infections, but its success stark when compared to jurisdictions that haven’t implemented status-neutral care, or scaled up access to health care. The hotspots of HIV transmission today are in some of the poorest states that have refused to expand Medicaid, like Mississippi.

Daskalakis said his efforts prove the concept works, but he points to the challenges inherent in a model based on the distribution of expensive medications. “A lot of people doing this work are going from, ‘So now we can do it, we know we can,’ to 'How do you create sustainability?'”

Daskalakis describes the city’s new status-neutral-care regime as “the steam engine that's rolling through HIV in New York City and mowing it down in a pretty aggressive way.”

“We're reaping the benefits by consistently seeing HIV incidence decrease,” he said. Last week, in an announcement of the record low HIV incidence, the City of New York said the new data shows it is on target to meet its Ending the Epidemic goals by 2020.

Comments