COVID-19 and The Inside of a NYC Funeral Home

(Popular Mechanics)

Patrick Kearns, 50, is a fourth generation funeral director in his family’s business. He has never turned a client away in his 25 years on the job. Then came COVID-19.

Unless he’s with a customer, Kearns is constantly texting or talking to someone through the AirPod in his left ear. His shaggy hair is hidden under a baseball cap (“all the barbers are closed,” he says). He plucks a stack of papers from the fax machine and adds it to a pile as thick as a dictionary. Each sheet represents another death, another bereaved family member looking for help. “I don’t think the printer is set up to handle this kind of volume,” says Kearns.

The funeral home’s answering service has been inundated with calls from people who have recently lost family members to COVID-19. Kearns figures he receives about 100 of them a day right now. Even while working well into the night, he still only manages to return about 30 calls.

This isn’t how Kearns likes to do business. Funerals are typically personal affairs—the director becomes as intimate as a family member, using a gentle touch to guide their clients through the toughest times of their lives.

“NO PART OF THE SYSTEM WAS BUILT TO HANDLE THIS VOLUME.”

Data collected in 2017 shows that on an average day, 149 people die in New York City. But COVID-19 alone is now killing 200, 300, or 400 a day. For three days in early April, the daily spike was in excess of 500. Over the course of about six weeks, the virus has killed at least 9,900 people in New York City—and that doesn’t include those who died at home or in nursing homes without receiving a coronavirus test.

Caskets are stored in warehouse space at the Leo F. Kearns Funeral Home in Richmond Hills, NY.

Caskets are stored in warehouse space at the Leo F. Kearns Funeral Home in Richmond Hills, NY.

In an effort to stanch the flood of funeral requests, Kearns pulled his company’s Google advertising. But the calls kept coming. He’d help more people if he could, but the problem isn’t just him. As with all cities, New York is limited by the capacity of its crematories and cemeteries. It can’t process more bodies than they can accept. “There’s just a tremendous bottleneck in every aspect,” says Kearns. “No part of the system was built to handle this volume.”

City officials have already given crematories permission to operate through the night, and they’ve encouraged cemeteries to postpone or livestream ceremonies whenever possible. To buy the system time, FEMA deployed 85 refrigerated tractor trailers across the city to hold bodies. The New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner will use these trucks to provide 15 days of storage, but if the family can’t claim the body in that time, remains will be temporarily interred at the city’s mass gravesite on Hart Island.

For more than 150 years, New York has used the uninhabited Bronx island to bury unclaimed bodies, along with those belonging to families unable to afford funerals. The island holds more than a million human remains, but no tombstones.

Kearns doesn’t want to see bodies going to Hart Island, so in early April, he shelled out for the reefer. At 8x40 feet, it should be able to accommodate 30 bodies.

Temporary shelving units and cardboard caskets are piled up near the refrigerator where bodies are stored before they are sent to the crematory. Kearns says the refrigerator is big enough to hold two bodies, which normally is plenty of space.

The company selling the container, At Your Service Tent and Event Rentals, usually works wedding parties. But when social gatherings were put on hold, At Your Service began working with hospitals around the city. Tents where fathers typically toast their daughters have been re-appropriated for triage support and privacy during the loading and unloading of COVID-19 casualties. As At Your Service saw morgues filling up, it began calling funeral homes, offering to provide reefers. Kearns was lucky enough to have the space.

Now he’s somewhat worried he’ll be stuck with the giant fridge forever. But he says, “the reality is when I no longer need it in New York, it will very likely be needed somewhere else.”

More Deaths, More Risks

Here’s what usually happens when someone dies at a hospital: The family calls the funeral home, and within a couple hours, someone arrives to collect the deceased. Because of the quick turnover, the typical hospital morgue is big enough for just 10 or 12 bodies.

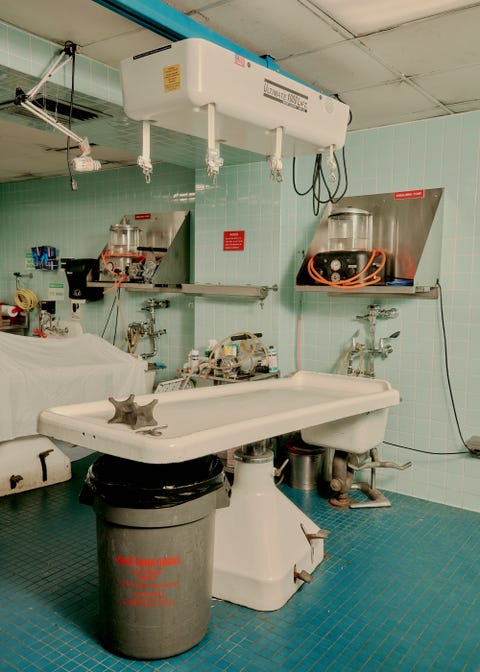

Once in the funeral home’s possession, the body will either be embalmed for burial or moved to cold storage to await cremation. An embalmed body will last at least two weeks without decomposing; a refrigerated body, a couple months. But these durations are rarely tested since most remains are buried or cremated within three days, and funeral homes aren’t generally equipped for long-term storage. Kearns has two embalming tables and a refrigerator big enough for just two bodies. “It’s actually empty most of the time,” he says.

The surge has changed the way remains move through the system. Now, families call around desperately, trying to find a funeral home that can handle one more case before their 15-day window closes. But funeral directors like Kearns are already overwhelmed.

(RESEARCHERS RECENTLY REPORTED THE THE FIRST COVID-19 TRANSMISSION FROM A DEAD TO LIVING HOST.)

There are only four crematories in New York City—two in Queens, one in the Bronx, and one in Brooklyn. Each of them can process about 20 bodies a day, which puts only a small dent in the number filing into the morgues.

Funerals are the other option, but burial is a relatively slow affair. Normally, a backhoe digs a hole, then the cemetery crew stages the ceremony with artificial grass to cover the dirt and a temporary device that displays the casket before lowering it. Friends and family visit, and after they disperse, a second team arrives to pack everything away before the backhoe returns to fill in the earth.

When coronavirus broke out in New York, many cemeteries actually scaled back their interment schedules so their staffs could maintain social distancing. To accommodate the surge in burials, Kearns and other funeral directors began advocating to forgo the ceremonial greens and lowering device. Eventually the cemeteries relented, and now they’re back to burying people at pre-COVID rates. When the hearse arrives, “it’s just four guys and two nylon straps,” says Kearns. It eases the bottleneck slightly, but not enough to keep up with the incoming dead.

At the funeral home, with bodies that require embalming, directors have to grapple with new risks. “You can have discharge from the lungs when you move the body,” says Kearns. Moisture coming up through the airway is one possibility. Another is a purge that, according to a Funeral Service Academy handbook, looks like coffee grounds seeping up from the lungs or stomach, trickling out through the mouth and nose. It’s typically brown, but when it comes from the lungs, it can take on a frothy consistency with a copper tint. In either case, the threat of infection is more than hypothetical, as researchers in Thailand recently reported the first COVID-19 transmission from a dead to living host.

At the funeral home, with bodies that require embalming, directors have to grapple with new risks. “You can have discharge from the lungs when you move the body,” says Kearns. Moisture coming up through the airway is one possibility. Another is a purge that, according to a Funeral Service Academy handbook, looks like coffee grounds seeping up from the lungs or stomach, trickling out through the mouth and nose. It’s typically brown, but when it comes from the lungs, it can take on a frothy consistency with a copper tint. In either case, the threat of infection is more than hypothetical, as researchers in Thailand recently reported the first COVID-19 transmission from a dead to living host.

To mitigate the risk, the staff is following precautionary protocols established to prevent the spread of tuberculosis. They’re wearing N95 masks, plus Tyvek suits or aprons. Manufactured by DuPont, Tyvek is made from high-density polyethylene filaments that block out microbes and resist abrasion.

Upon opening a body bag, the embalmer sprays the deceased's eyes, nose, and throat with an alcohol-based embalming disinfectant called Dis-Spray. Rolls of cotton batting are in ready supply in funeral homes: Embalmers normally pack it into orifices to prevent seepage and to give faces a fuller, more life-like appearance. Now they’re also using it to prevent disease transmission. So after the initial spritz, the embalmer soaks a panel of batting with more Dis-Spray and places it over the deceased’s face.

It’s all best practice, but in reality, Kearns and his staff generally operate in more casual gear. “Up until these COVID cases, I would just roll up the sleeves of my white shirt, put on an apron and a pair of gloves, and embalm the body,” he says.

After the Dis-Spray treatment, the process proceeds as usual: The embalmer inserts a scalpel into the center of the carotid artery and opens an incision just big enough to accommodate a thin steel tube. Slowly, to prevent swelling, he or she pumps in a cocktail that includes formaldehyde, anticoagulant, and humectant, a class of chemicals that keep tissue hydrated and pliable. There’s also some pink dye to add life-like color, and the embalmer might gently massage the hands and feet to help coerce the fluid into capillaries in the fingers and toes. Two or three gallons go in, which forces about a third of the body’s blood to drain through a tube inserted near the heart.

The process generally takes one to two hours, and Kearns employs a few directors who can do the job. But one, an off-duty police officer who works part time, is particularly fast. These days, the officer is coming in before or after his shift to embalm two bodies a day, and earlier this month, he processed 30 cases over a three-day weekend. “He started working for us as a kid,” says Kearns. “His father was also a very good embalmer.”

|

To accommodate more bodies, Kearns lined his embalming room with plastic banquet tables and an array of rolling stretchers and carts. Once a body is treated, he says, it no longer poses an infection risk. It’s the family of the deceased that worries him more.

Occasionally people who are unable to get through on the phone show up at the funeral home unannounced. Kearns has to explain to them that they’re potentially exposing his employees to the virus. The funeral home staff no longer holds the front door for guests, and the welcome desk is cordoned off with theater rope.

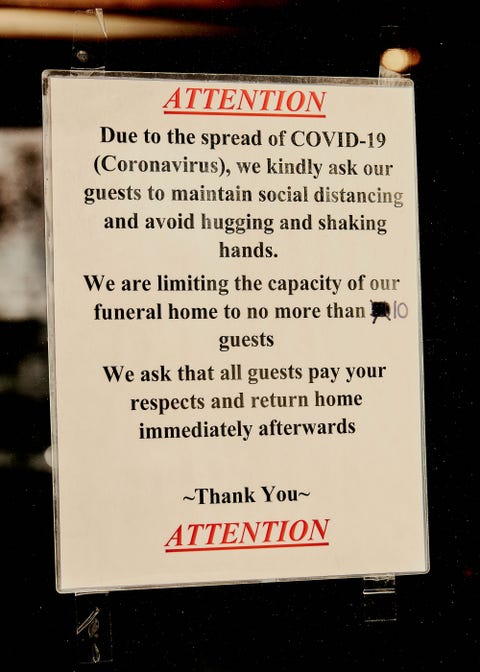

A sign at the entrance encourages people to avoid hugging or shaking hands, and in accordance with CDC guidelines, ceremonies are limited to 10 people. Burying a loved one is hard enough, but it’s a particularly rough ordeal when you add the lonely image of a few chairs floating in a room that’s built for 120.

An Unrelenting Effort

As the shelves come together inside the shipping container, Patrick’s business partner and brother-in-law, Paul Kearns-Stanley, walks out wearing blue rubber gloves and a white Tyvek embalming suit that looks like a plastic onesie. Paul looks from the pile of lumber to the scaffolding that’s starting climb up the reefer’s wall. “Are we going to put people in here tonight?” he asks.

“I hope so,” says Kearns, typing on his phone. “The electrician is supposed to come later.”

Before the container arrived, Kearns had found a crematorium three hours north of the city, in Schenectady, that could process four bodies a day for him. There and back, the drive will require a full day’s work. But he’ll send somebody every day. If he can figure out how, he might even send two vans.

Back inside, Kearns grabs a deli sandwich from a plastic tray in the break room. He’s too hurried to involve a plate or napkin, but he manages to take two bites during the walk to the building’s administrative office. “I have to remember to eat,” he says. In March Kearns weighed 150 pounds, but after a month of late nights and early mornings, he is down to 137. His crisp white shirt appears to be a size too big.

He sets the stack of bread and meat on a table and begins examining the cardboard scheduling boards that track the progress of the bodies in his care. “Usually funerals are in and out in three days,” he says. “I like it like that. I’m not a good long-term planner.”

|

A secretary in a black N95 mask interrupts. It’s the electrician, she says, he can’t come today. The refrigerated container will have to wait. Kearns takes a third bite of his sandwich.

The next morning, when the electrician does arrive, he discovers a problem. They need a transformer. The refrigerator runs on a 440-volt motor, and the power coming from the funeral home is only 220.

The unrelenting effort is beginning to wear him down. Kearns worries he wasted several thousand dollars for a large piece of garbage. “I don’t know what I’m doing here,” he says. “I don’t even know what I bought.” He calls At Your Service, and they assure him everything’s okay. They can get him the transformer. It’ll cost him nearly $2,000, but he’ll have it today.

What can seem strange here is how the situation for death-care workers remains so dire even as the number of new coronavirus cases begins to level off. The curve is flattening, but people are still dying at rates far higher than usual, and the trailers, tents, and shipping containers around New York can only hold so many bodies. “We’re being challenged here with an enormous task,” says Kearns. “When we look back, we’ll say, ‘How did we respond? What did we do to help?’” He trails off for a moment, but then comes back. “I’ve seen and been in the trailers full of dead bodies,” he says. “It’s not dramatizing it to say that this is a war.”

By 3 o’clock, the makeshift morgue is up and running, and Kearns immediately begins wheeling bodies from the embalming room.

The next day, the container is at capacity.

Comments