Hurricane Season is Coming To PR But What Are HIV+ Supposed to Do? Run Away or Hunker Down

As Puerto Rico Battles Hurricane Season, HIV-Positive Folks Begin To Brace For The Worst

With the coronavirus spreading and natural disasters intensifying, HIV-positive Puerto Ricans are having to decide to flee — or stay and fight for their lives.

SAN JUAN — When Alexi Díaz León returned to Puerto Rico in the summer of 2017, he had just lost his job, was dealing with a crystal meth addiction, and hadn’t been on HIV treatment for a year. Afraid he was going to end up homeless in Miami, he enlisted a friend’s help to get back to the island where he was born.

But less than three months after the homecoming that allowed him to quickly find medical care to begin treatment for drug addiction and to manage his HIV, the scenery took a dark turn when Hurricane Maria struck that September.

As the storm approached the island, Díaz León, 39, knew that the already fragile HIV infrastructure in Puerto Rico would potentially fall in the days that would follow. So he refilled his medication before the storm made landfall, getting himself a one-and-a-half-month supply that would provide some crucial stability in the aftermath of the storm.

Once Maria made landfall on the Caribbean island, life for most residents was immediately turned upside down as the electrical grid was decimated, infrastructure shattered, and thousands were left without aid of any kind, some even to this day. While Díaz León’s foresight so early into his treatment helped him literally weather the storms, he says not to call him “resilient.”

“I don't like that word because that word to me is from an American experience,” he recently told BuzzFeed LGBTQ. “It’s not resilience; it’s just survival. We have learned to survive, so I don't like ‘resilience’ because it’s also making emphasis on our colonial status.”

But while Díaz León was able to manage his HIV after 2017’s catastrophic storms, many weren’t. For those without access to HIV treatment, that meant the virus went unchecked and their condition worsened.

And now as the island finds itself in the throes of an abnormally busy Hurricane season that experts say could produce nearly 20 named storms in the Atlantic Ocean, and the coronavirus continuing to rage, Díaz León is just one of thousands of Puerto Ricans living with HIV who are worrying about just how much more they can bear.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, some living with HIV on the island saw a more than 10% increase in the virus in their body, known as a viral load, according to preliminary data from Columbia University. And as issues significantly impacting access to treatment continue, HIV-positive Puerto Ricans could see this number continue to climb, putting their health and hopes of combating the spread of HIV on the island in even greater jeopardy.

Activists and public health experts have long argued that an ongoing healthcare crisis and billions of dollars in government debt made it difficult to access treatment for HIV on the island even before it was battered by recent storms and earthquakes. And now those long-standing struggles for HIV treatment are being further compounded by other now-worsened public health issues including homelessness and COVID-19, which impacts immunocompromised people at significantly higher rates.

The scope of the coronavirus on the island so far is unclear due to incomplete and inaccurate data from the local government. In late April, the island’s government trimmed the number of positive cases to remove ones that had been counted twice, and since then, the government has not reported negative testing numbers, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Carlos Rodríguez-Díaz, an associate professor at George Washington University specializing in community health, said a dangerous dearth of research on how the coronavirus impacts any person living with HIV has only added to that lack of clarity, especially on the island.

“We are seeing again the challenges of being a colony and not having independence to make certain decisions,” he said.

A view of a house destroyed by Hurricane Maria, in Yabucoa, in the eastern of Puerto Rico. The Not-So-Calm Before the Storms An envelope and a look of pity from a lab employee were how Jorge Santiago, 43, said he found out he had HIV while living in Puerto Rico in 2006.

“I got the news on a Friday and I had to go to work on Monday like nothing happened,” Santiago told BuzzFeed LGBTQ. And his experience with HIV treatment on the island didn’t get better. In fact, he said, it’s one of the reasons he left the island permanently in 2010 for New York City. He called the treatment on the island “very messy” and said he would often have to wake up at 4 a.m. to be seen by 9:30 a.m. for a routine checkup at a state hospital every three months — an ordeal he said was normal at other clinics and doctors offices as well.

Once he reached New York City, however, he said it took him just three days to get connected to treatment. In Puerto Rico, he said his doctors waited four years to put him on medicine to treat his HIV.

Santiago blamed his experiences on outdated and anti-gay ideas about the virus on the island.

“I remember just being a kid during the AIDS crisis, and because there's always been so much homophobia in the island, it was really even more present,” Santiago said. “So when I was a teenager, and medication started to come out and there was more awareness coming out, people were still making AIDS jokes on the island and just kind of treating it as a gay disease.”

But even those who had more positive experiences seeking out HIV treatment on the island have fled the American colony for more robust healthcare.

A friend of Santiago’s, Eduardo Diaz, said he was diagnosed with HIV on the island in 2008 when he was 24. And just eight months later, he too left the island for the Empire State.

Unlike Santiago, Diaz said he was connected to HIV treatment in Puerto Rico fairly quickly after his diagnosis through a clinical trial. But even with that connection to treatment, Diaz said the impersonal, scientific nature of the clinical trial left him feeling like a guinea pig.

Once landing in New York, Diaz said he also got connected to treatment quickly, through the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center. And like Santiago, Diaz said the stark difference in HIV care between Puerto Rico and New York affected him deeply.

“It just honestly made me feel like a second-class citizen,” Diaz said. “I feel like what I'm getting now is what everyone in Puerto Rico deserves.”

But people living with HIV have sought out better treatment on the mainland for decades. Moisés Agosto-Rosario, 55, said he was diagnosed with HIV in Puerto Rico in 1986 during the height of the HIV epidemic. On the island, he said there was “no conversation” about the virus and how to treat it. He too left the island for New York City in 1988 and was invited to a meeting of the then–recently founded HIV activist group ACT UP.

“It was the first time I saw a bunch of people my age, mostly positive, with a more proactive attitude,” he said. “It was like a religious experience. I decided to stay.”

As for the source of those long-standing stigmas in Puerto Rico, GWU professor Rodríguez-Díaz said the typical stigmas that ascribe blame to people living with HIV and associate the virus with queerness and promiscuity are further complicated by conservativism, Latinx machismo, and Catholicism on the island — as well as the novel way HIV has spread in Puerto Rico.

According to local health department data, as of March 31, 2020, there have been a little more than 50,100 cumulative positive HIV or AIDS cases diagnosed in Puerto Rico. Among the more than 49,400 adults or adolescents diagnosed with HIV or AIDS, nearly half — 42% — contracted the virus solely through injection drug use — the main way the virus has been transmitted on the island.

In the mainland US, however, people who inject drugs made up 7% of new HIV diagnoses in 2018, and more than two-thirds of all national HIV diagnoses that year were among men who have sex with other men. Puerto Rico also had the 12th-highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the country in 2017, according to the CDC. Erika P. Rodríguez

Prevention specialist Franchely M. Soto-Rivera (far right) and nurse Alan J. Crespo-Villanueva (center), from Punto Fijo, stop at a community in the city to do needle exchange with people using drugs in San Juan, Aug. 10.

Alongside stigma, a historic lack of adequate funding has also impacted the quality of HIV care on the island.

The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission said in a June 2019 report to Congress that a 55% federal medical assistance percentage, the percentage of Medicaid program expenses paid by the federal government, and a capped allotment of funds in Puerto Rico have created what the bloc called “chronic underfunding” of Medicaid on the island. According to the report, Medicaid covered roughly half of the island’s population in 2017.

And according to data provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration, which administers a federal program known as the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, the funding provided has stayed relatively consistent on the island.

That consistency, HRSA spokesperson Elizabeth Senerchia said, is partly due to certain Ryan White funding being awarded based on living HIV/AIDS cases and on the federal appropriation, which Senerchia noted doesn’t take healthcare coverage in any jurisdiction into account.

But in light of that “chronic underfunding” of Medicaid services on the island that the Commission described, consistent Ryan White money could still leave a funding gap.

The island has also recently been facing a mass exodus of medical professionals, which leaves Puerto Ricans on the island with fewer and fewer healthcare options. As a specialized population in the medical field, people living with HIV have been seriously impacted by that dwindling number of doctors, said Naiska Guzman, coordinator for San Juan–based HIV clinic Center for Life.

The Puerto Rico College of Physicians and Surgeons told the Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico in September 2016 that, at the time, more than 4,000 physicians had left the island in the decade prior, shrinking the number on the island from 14,000 to 10,000.

Of the doctors who haven’t left the island, Guzman also said many have switched to more lucrative specializations or retired.

But as was the case for Diaz León, medical providers can create hurdles of their own. Diaz León said that when his government insurance plan, which he uses to pay for his HIV treatment, had expired, his doctor’s office didn’t tell him that his accompanying private health insurance would not cover his HIV treatment.

He said he was able to use connections in the government to get an appointment to renew his government insurance the following day. Oftentimes, those appointments can take a month or two, he said.

“I have been lucky because I have connections, but then that makes me think about all those people who aren't as lucky as me or who don't have the means in terms of time or transportation or information or the connections to fast pace this type of procedure,” Diaz León said. Natural and Unnatural Disasters

Roughly three years after hurricanes Maria and Irma hit the island, and months after massive earthquakes rocked the southern part of Puerto Rico, experts and the public have said the local government’s response to and readiness for natural disasters is still failing its people.

Helga Maldonado, a regional director of Escape, a nonprofit organization that works to prevent child abuse and domestic violence in Puerto Rico, told BuzzFeed LGBTQ in February that the government hadn’t learned from its mistakes and said the island’s health department was “invisible” in the areas impacted by the January earthquakes.

The response, Maldonado said, was particularly frustrating given the government’s heavily criticized actions following 2017’s deadly hurricanes. Many Puerto Ricans say that it was the community organizations and activists, not government officials, who have been the primary sources of help after the disasters.

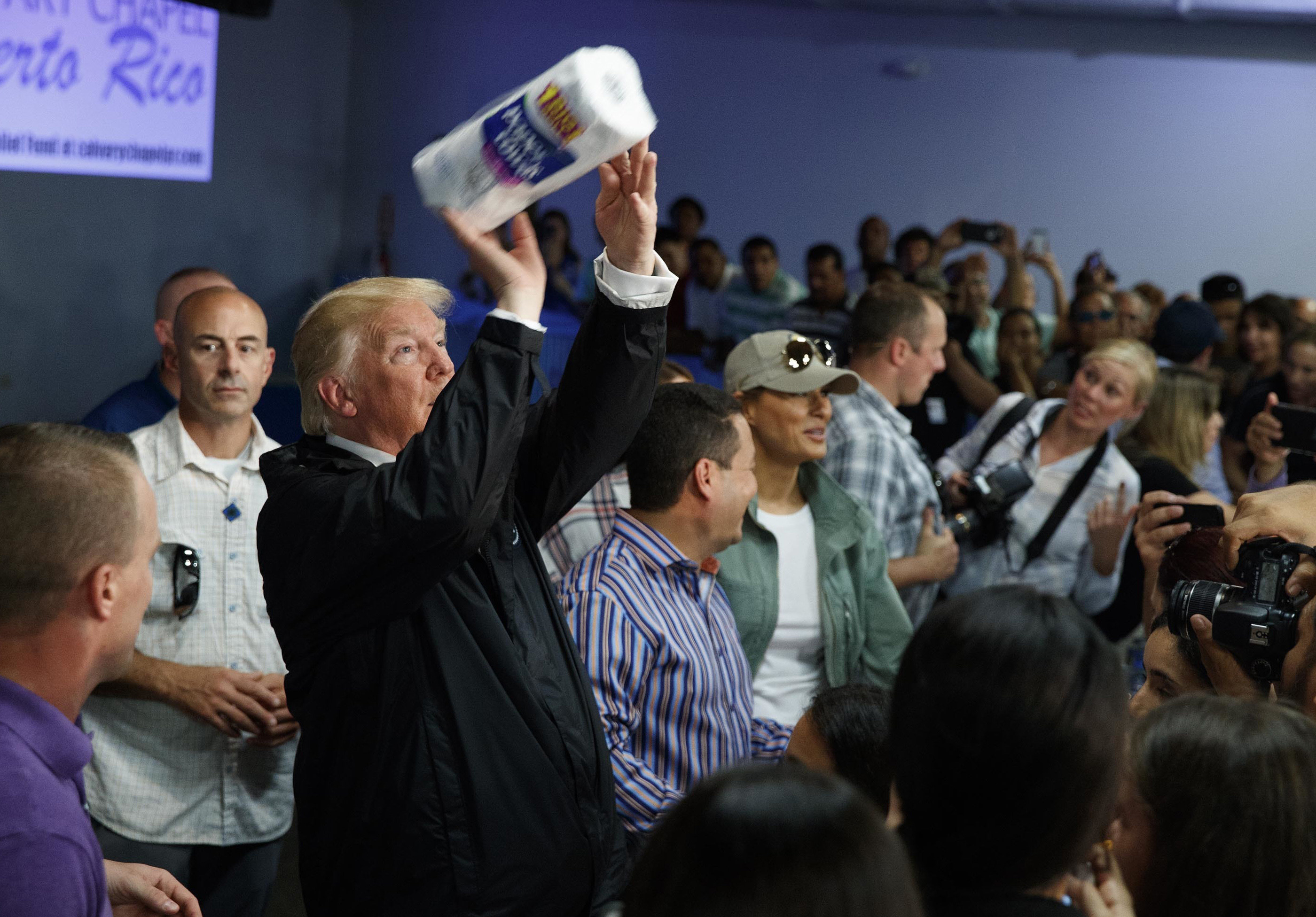

“All they’ve done is throw paper towels at us,” Maldonado said, referring to President Donald Trump’s infamous visit to the island after the 2017 storms.

Elaine C. Duke, former acting Homeland Security secretary under Trump, told the New York Times in an interview published in early July that Trump had also brought up selling the colony after the catastrophic storms in 2017. Duke said in the interview that the idea was never seriously considered after Trump had raised it. Evan Vucci / AP

President Donald Trump tosses paper towels into a crowd as he hands out supplies at Calvary Chapel, in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, Oct. 3, 2017.

In June 2017, six members of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS stepped down in protest, and months later in December, the Trump administration fired the remaining council members. The council was eventually restaffed in March 2019, one month after Trump pledged to reduce new HIV infections by 90% in the next 10 years. The CDC website states that as part of that plan, the San Juan municipality in Puerto Rico was designated as one of 57 “geographic focus areas” that will be given additional resources to fight the epidemic.

Rodríguez-Díaz said that while the initiative provided more resources to those fighting the epidemic, in practice, those efforts have been hampered by infrastructure on the island that isn’t equipped to expand so quickly. He added that the recent spate of natural disasters and ensuing recovery efforts have only slowed down the process of actually using putting those resources to work.

Anselmo Fonseca, the program manager for Puerto Rico initiatives at AIDS United, said he was trapped in the mountains for days and lost 15 pounds after the 2017 storms.

Fonseca spoke of hourslong lines for gas and ATMs, $200 withdrawal limits, and empty grocery shelves. He said a generator, a hybrid car, and stockpiled cash and medication helped him weather the storm as best possible. He, like many, have had to rebuild after the disasters without any help from the government.

For other HIV-positive Puerto Ricans like him, Fonseca said help from the government seems unlikely.

“All they’ve done is throw paper towels at us."

“Clearly, we're going to be, again, an afterthought,” Fonseca said, referring to the current state of the island as hurricane seasons continues, adding: “Keep in mind that COVID has basically left folks poorer, so most are still just trying to get by.”

For people living with HIV to survive in Puerto

Rico, particularly amid continuing disasters, Fonseca said basic necessities like medication are essential. But disasters, natural and otherwise, have made securing that treatment difficult for many.

“It’s a slow recovery process and I’m able to, but there are thousands more unlike me who are unable to and have no access to any dollars to help and have to rely on the kindness of organizations.”

Fonseca said some survivors of the earthquakes who are HIV-positive were too afraid to go inside their damaged homes to get their much-needed medication. For each of these people, and the others living with HIV on the island after the disasters, the virus only adds to their struggles, he said.

“As a long-term survivor, you know there’s various things that you have to deal with, and first that’s having enough bottles of water, enough canned goods, and your medication,” he said.

Without medication, a viral load will begin to increase in roughly two weeks, said Margaret Hoffman-Terry, chair of the American Academy of HIV Medicine board of directors. And based on early data from Columbia University, that is exactly what happened on the island.

Following Hurricane Maria, the average viral load was 11% higher than before the storm, according to a study written by Columbia University associate professor of sociomedical sciences Diana Hernandez that analyzed data of people living with HIV from the San Juan metropolitan area who also have a history of substance use.

A rising viral load isn’t the only risk, however. Hoffman-Terry said people living with HIV run the risk of becoming resistant to the ingredients in their medications each time they go off — or lose access to — their medication.

Rodríguez-Díaz said many people living with HIV told him after the hurricane that their treatment and care were not impacted by the storm. But upon investigation, he found another story.

In the aftermath of the hurricanes, people living with HIV who ran out of their medication would reach out to others living with the virus and would share medication while they were figuring out how to get a refill, Rodríguez-Díaz said.

“[Their survival] wasn’t because we as a system or as providers did something extraordinary," Rodríguez-Díaz said. "It’s because they figured it out.”

“We are in a day and age that shouldn't be happening,” he said. “It was scary to see that in general people’s health could be in jeopardy because of our structure, meaning our political structure.”

But the island’s struggles aren’t only the fault of the Trump administration or its inadequate response to the compounding crises on the island.

A highly criticized financial oversight board, tasked with overseeing the restructuring of the island’s billions in debt, is a product of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, also known as PROMESA. The law was signed under President Barack Obama in June 2016. According to MacPac’s June 2019 report, Puerto Rico’s debt in 2017 comprised $74 billion in bond debt and an additional $49 billion in unfunded pension obligations.

Many on the island, however, see the board as just another symbol of the island’s colonial status. The US Supreme Court ruled in June 2020 that the unelected members of the board had been properly appointed by the president.

Stigma, Shame, and Syringes

As storms, hurricanes, and a lackadaisical government have impacted the quality of care for people living with HIV, many experts and advocates said internal and external stigma plays a huge role in how — and if — people access care, as well as the quality of that care.

Naiska Guzman, the coordinator of the Center for Life clinic, said some patients living with HIV — weighed down by stigma — even refuse to tell their doctors about their condition. Doctors who blame patients for their diagnoses can also be particularly emotionally damaging, she said.

“HIV is not a punishment; HIV is a condition like diabetes or cholesterol,” she said. “People don’t ask how you get cancer when you say you have cancer, but if you say you have HIV, people question you. We need to talk openly about HIV. If we don’t talk about HIV, the stigma is going to continue to be a barrier.” That stigma, and government neglect, were on full display during the first stop of a two-hour needle exchange in San Juan with outreach workers Antonio Cintron and Raphael Torres this past February, who were once addicted to drugs themselves. The pair are a part of a local harm reduction group called Iniciativa Comunitaria.

On that hot, late morning in mid-February, a middle-aged HIV-positive man slowly shuffled to the back of Cintron’s nearly 30-year-old white Pontiac. Wearing only bright blue athletic shorts and black socks with no shirt, his brown skin was riddled with ulcers, scars, and scabs. Cintron said the man is the de facto leader of a group of other people addicted to drugs that live in the abandoned house from which he emerged.

The shirtless man dumped a plastic jug of used syringes into a red biohazard box and in kind received a plastic shopping bag full of condoms, clean needles, tourniquets, and other tools that are crucial to safely injecting drugs at the house. In a gravelly, strained voice, he said in Spanish that he had no ID and had no way to access important services he desperately needed, such as referrals to HIV care and drug treatment programs.

Over the two hours spent on the needle exchange, people simultaneously experiencing homelessness and addiction to drugs spoke of a condition only worsened by natural disasters. They flowed from abandoned houses and overgrown lots; they lined up for 20 clean needles each, condoms, and tourniquets. Many, but not all, had open sores, sunken faces, and loose clothes. One man dropped off used needles on his way to work at a local car dealership.

“We will be seeing the effects of this pandemic in our participants for a long time."

Alex Serrano, the director of community relations at Iniciativa Comunitaria, said the group nonetheless continues its needle exchange and harm reduction work amid these compounding disasters.

Serrano said that since the start of the pandemic, the group set up a portable handwashing station for needle exchange participants, limits the needle exchange routes to Monday mornings, and additionally passes out COVID-19 information to participants.

Before Tropical Storm Isaias reached the island, Serrano said the group was also giving out information about the storm and shelters.

Serrano said he was one of more than 400,00 people who lost power on the island after Isaias, and amid all these dogpiling disasters, he said some treatment services, particularly detox services for people living with drug addiction, are hard to come by.

The people Iniciativa serves are Puerto Ricans at their most vulnerable, and almost everyone who Cintron spoke with said that if they could access treatment — if they had the money, IDs, or just plain help to do so — they would.

“This is so new for all of us,” Serrano said. “We will be seeing the effects of this pandemic in our participants for a long time."

For Díaz León — and many Puerto Ricans like him who are living with HIV — recovering from the latest disaster and preparing for the next, whether it be natural, political or both, mirrors what brought him back to the island back in 2017: hoping for the best and taking things one day at a time.

And wondering if meaningful help will ever arrive.

Comments